Microwave

Microwave is a form of electromagnetic radiation with wavelengths shorter than other radio waves but longer than infrared waves. Its wavelength ranges from about one meter to one millimeter, corresponding to frequencies between 300 MHz and 300 GHz, broadly construed.[1][2]: 3 [3][4][5][6][excessive citations] A more common definition in radio-frequency engineering is the range between 1 and 100 GHz (wavelengths between 30 cm and 3 mm),[2]: 3 or between 1 and 3000 GHz (30 cm and 0.1 mm).[7][8] The prefix micro- in microwave is not meant to suggest a wavelength in the micrometer range; rather, it indicates that microwaves are small (having shorter wavelengths), compared to the radio waves used in prior radio technology.

The boundaries between far infrared, terahertz radiation, microwaves, and ultra-high-frequency (UHF) are fairly arbitrary and are used variously between different fields of study. In all cases, microwaves include the entire super high frequency (SHF) band (3 to 30 GHz, or 10 to 1 cm) at minimum. A broader definition includes UHF and extremely high frequency (EHF) (millimeter wave; 30 to 300 GHz) bands as well.

Frequencies in the microwave range are often referred to by their IEEE radar band designations: S, C, X, Ku, K, or Ka band, or by similar NATO or EU designations.

Microwaves travel by line-of-sight; unlike lower frequency radio waves, they do not diffract around hills, follow the earth's surface as ground waves, or reflect from the ionosphere, so terrestrial microwave communication links are limited by the visual horizon to about 40 miles (64 km). At the high end of the band, they are absorbed by gases in the atmosphere, limiting practical communication distances to around a kilometer.

Microwaves are widely used in modern technology, for example in point-to-point communication links, wireless networks, microwave radio relay networks, radar, satellite and spacecraft communication, medical diathermy and cancer treatment, remote sensing, radio astronomy, particle accelerators, spectroscopy, industrial heating, collision avoidance systems, garage door openers and keyless entry systems, and for cooking food in microwave ovens.

Electromagnetic spectrum

Microwaves occupy a place in the electromagnetic spectrum with frequency above ordinary radio waves, and below infrared light:

| Electromagnetic spectrum | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Wavelength | Frequency (Hz) | Photon energy (eV) | |

| Gamma ray | < 0.01 nm | > 30 EHz | > 124 keV | |

| X-ray | 0.01 nm – 10 nm | 30 EHz – 30 PHz | 124 keV – 124 eV | |

| Ultraviolet | 10 nm – 400 nm | 30 PHz – 750 THz | 124 eV – 3 eV | |

| Visible light | 400 nm – 750 nm | 750 THz – 400 THz | 3 eV – 1.7 eV | |

| Infrared | 750 nm – 1 mm | 400 THz – 300 GHz | 1.7 eV – 1.24 meV | |

| Microwave | 1 mm – 1 m | 300 GHz – 300 MHz | 1.24 meV – 1.24 μeV | |

| Radio | ≥ 1 m | ≤ 300 MHz | ≤ 1.24 μeV | |

In descriptions of the electromagnetic spectrum, some sources classify microwaves as radio waves, a subset of the radio wave band, while others classify microwaves and radio waves as distinct types of radiation.[1] This is an arbitrary distinction.

Frequency bands

Bands of frequencies in the microwave spectrum are designated by letters. Unfortunately, there are several incompatible band designation systems, and even within a system the frequency ranges corresponding to some of the letters vary somewhat between different application fields.[9][10] The letter system had its origin in World War 2 in a top-secret U.S. classification of bands used in radar sets; this is the origin of the oldest letter system, the IEEE radar bands. One set of microwave frequency bands designations by the Radio Society of Great Britain (RSGB), is tabulated below:

| Radio bands | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITU | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| EU / NATO / US ECM | ||||||||||||

| IEEE | ||||||||||||

| Other TV and radio | ||||||||||||

| Designation | Frequency range | Wavelength range | Typical uses |

|---|---|---|---|

| L band | 1 to 2 GHz | 15 cm to 30 cm | military telemetry, GPS, mobile phones (GSM), amateur radio |

| S band | 2 to 4 GHz | 7.5 cm to 15 cm | weather radar, surface ship radar, some communications satellites, microwave ovens, microwave devices/communications, radio astronomy, mobile phones, wireless LAN, Bluetooth, ZigBee, GPS, amateur radio |

| C band | 4 to 8 GHz | 3.75 cm to 7.5 cm | long-distance radio telecommunications, wireless LAN, amateur radio |

| X band | 8 to 12 GHz | 25 mm to 37.5 mm | satellite communications, radar, terrestrial broadband, space communications, amateur radio, molecular rotational spectroscopy |

| Ku band | 12 to 18 GHz | 16.7 mm to 25 mm | satellite communications, molecular rotational spectroscopy |

| K band | 18 to 26.5 GHz | 11.3 mm to 16.7 mm | radar, satellite communications, astronomical observations, automotive radar, molecular rotational spectroscopy |

| Ka band | 26.5 to 40 GHz | 5.0 mm to 11.3 mm | satellite communications, molecular rotational spectroscopy |

| Q band | 33 to 50 GHz | 6.0 mm to 9.0 mm | satellite communications, terrestrial microwave communications, radio astronomy, automotive radar, molecular rotational spectroscopy |

| U band | 40 to 60 GHz | 5.0 mm to 7.5 mm | |

| V band | 50 to 75 GHz | 4.0 mm to 6.0 mm | millimeter wave radar research, molecular rotational spectroscopy and other kinds of scientific research |

| W band | 75 to 110 GHz | 2.7 mm to 4.0 mm | satellite communications, millimeter-wave radar research, military radar targeting and tracking applications, and some non-military applications, automotive radar |

| F band | 90 to 140 GHz | 2.1 mm to 3.3 mm | SHF transmissions: Radio astronomy, microwave devices/communications, wireless LAN, most modern radars, communications satellites, satellite television broadcasting, DBS, amateur radio |

| D band | 110 to 170 GHz | 1.8 mm to 2.7 mm | EHF transmissions: Radio astronomy, high-frequency microwave radio relay, microwave remote sensing, amateur radio, directed-energy weapon, millimeter wave scanner |

Other definitions exist.[11]

The term P band is sometimes used for UHF frequencies below the L band but is now obsolete per IEEE Std 521.

When radars were first developed at K band during World War 2, it was not known that there was a nearby absorption band (due to water vapor and oxygen in the atmosphere). To avoid this problem, the original K band was split into a lower band, Ku, and upper band, Ka.[12]

Propagation

Microwaves travel solely by line-of-sight paths; unlike lower frequency radio waves, they do not travel as ground waves which follow the contour of the Earth, or reflect off the ionosphere (skywaves).[13] Although at the low end of the band, they can pass through building walls enough for useful reception, usually rights of way cleared to the first Fresnel zone are required. Therefore, on the surface of the Earth, microwave communication links are limited by the visual horizon to about 30–40 miles (48–64 km). Microwaves are absorbed by moisture in the atmosphere, and the attenuation increases with frequency, becoming a significant factor (rain fade) at the high end of the band. Beginning at about 40 GHz, atmospheric gases also begin to absorb microwaves, so above this frequency microwave transmission is limited to a few kilometers. A spectral band structure causes absorption peaks at specific frequencies (see graph at right). Above 100 GHz, the absorption of electromagnetic radiation by Earth's atmosphere is so effective that it is in effect opaque, until the atmosphere becomes transparent again in the so-called infrared and optical window frequency ranges.

Troposcatter

In a microwave beam directed at an angle into the sky, a small amount of the power will be randomly scattered as the beam passes through the troposphere.[13] A sensitive receiver beyond the horizon with a high gain antenna focused on that area of the troposphere can pick up the signal. This technique has been used at frequencies between 0.45 and 5 GHz in tropospheric scatter (troposcatter) communication systems to communicate beyond the horizon, at distances up to 300 km.

Antennas

The short wavelengths of microwaves allow omnidirectional antennas for portable devices to be made very small, from 1 to 20 centimeters long, so microwave frequencies are widely used for wireless devices such as cell phones, cordless phones, and wireless LANs (Wi-Fi) access for laptops, and Bluetooth earphones. Antennas used include short whip antennas, rubber ducky antennas, sleeve dipoles, patch antennas, and increasingly the printed circuit inverted F antenna (PIFA) used in cell phones.

Their short wavelength also allows narrow beams of microwaves to be produced by conveniently small high gain antennas from a half meter to 5 meters in diameter. Therefore, beams of microwaves are used for point-to-point communication links, and for radar. An advantage of narrow beams is that they do not interfere with nearby equipment using the same frequency, allowing frequency reuse by nearby transmitters. Parabolic ("dish") antennas are the most widely used directive antennas at microwave frequencies, but horn antennas, slot antennas and lens antennas are also used. Flat microstrip antennas are being increasingly used in consumer devices. Another directive antenna practical at microwave frequencies is the phased array, a computer-controlled array of antennas that produces a beam that can be electronically steered in different directions.

At microwave frequencies, the transmission lines which are used to carry lower frequency radio waves to and from antennas, such as coaxial cable and parallel wire lines, have excessive power losses, so when low attenuation is required, microwaves are carried by metal pipes called waveguides. Due to the high cost and maintenance requirements of waveguide runs, in many microwave antennas the output stage of the transmitter or the RF front end of the receiver is located at the antenna.

Design and analysis

The term microwave also has a more technical meaning in electromagnetics and circuit theory.[14][15] Apparatus and techniques may be described qualitatively as "microwave" when the wavelengths of signals are roughly the same as the dimensions of the circuit, so that lumped-element circuit theory is inaccurate, and instead distributed circuit elements and transmission-line theory are more useful methods for design and analysis.

As a consequence, practical microwave circuits tend to move away from the discrete resistors, capacitors, and inductors used with lower-frequency radio waves. Open-wire and coaxial transmission lines used at lower frequencies are replaced by waveguides and stripline, and lumped-element tuned circuits are replaced by cavity resonators or resonant stubs.[14] In turn, at even higher frequencies, where the wavelength of the electromagnetic waves becomes small in comparison to the size of the structures used to process them, microwave techniques become inadequate, and the methods of optics are used.

Sources

High-power microwave sources use specialized vacuum tubes to generate microwaves. These devices operate on different principles from low-frequency vacuum tubes, using the ballistic motion of electrons in a vacuum under the influence of controlling electric or magnetic fields, and include the magnetron (used in microwave ovens), klystron, traveling-wave tube (TWT), and gyrotron. These devices work in the density modulated mode, rather than the current modulated mode. This means that they work on the basis of clumps of electrons flying ballistically through them, rather than using a continuous stream of electrons.

Low-power microwave sources use solid-state devices such as the field-effect transistor (at least at lower frequencies), tunnel diodes, Gunn diodes, and IMPATT diodes.[16] Low-power sources are available as benchtop instruments, rackmount instruments, embeddable modules and in card-level formats. A maser is a solid-state device that amplifies microwaves using similar principles to the laser, which amplifies higher-frequency light waves.

All warm objects emit low level microwave black-body radiation, depending on their temperature, so in meteorology and remote sensing, microwave radiometers are used to measure the temperature of objects or terrain.[17] The sun[18] and other astronomical radio sources such as Cassiopeia A emit low level microwave radiation which carries information about their makeup, which is studied by radio astronomers using receivers called radio telescopes.[17] The cosmic microwave background radiation (CMBR), for example, is a weak microwave noise filling empty space which is a major source of information on cosmology's Big Bang theory of the origin of the Universe.

Applications

Microwave technology is extensively used for point-to-point telecommunications (i.e., non-broadcast uses). Microwaves are especially suitable for this use since they are more easily focused into narrower beams than radio waves, allowing frequency reuse; their comparatively higher frequencies allow broad bandwidth and high data transmission rates, and antenna sizes are smaller than at lower frequencies because antenna size is inversely proportional to the transmitted frequency. Microwaves are used in spacecraft communication, and much of the world's data, TV, and telephone communications are transmitted long distances by microwaves between ground stations and communications satellites. Microwaves are also employed in microwave ovens and in radar technology.

Communication

Before the advent of fiber-optic transmission, most long-distance telephone calls were carried via networks of microwave radio relay links run by carriers such as AT&T Long Lines. Starting in the early 1950s, frequency-division multiplexing was used to send up to 5,400 telephone channels on each microwave radio channel, with as many as ten radio channels combined into one antenna for the hop to the next site, up to 70 km away.

Wireless LAN protocols, such as Bluetooth and the IEEE 802.11 specifications used for Wi-Fi, also use microwaves in the 2.4 GHz ISM band, although 802.11a uses ISM band and U-NII frequencies in the 5 GHz range. Licensed long-range (up to about 25 km) Wireless Internet Access services have been used for almost a decade in many countries in the 3.5–4.0 GHz range. The FCC recently[when?] carved out spectrum for carriers that wish to offer services in this range in the U.S. — with emphasis on 3.65 GHz. Dozens of service providers across the country are securing or have already received licenses from the FCC to operate in this band. The WIMAX service offerings that can be carried on the 3.65 GHz band will give business customers another option for connectivity.

Metropolitan area network (MAN) protocols, such as WiMAX (Worldwide Interoperability for Microwave Access) are based on standards such as IEEE 802.16, designed to operate between 2 and 11 GHz. Commercial implementations are in the 2.3 GHz, 2.5 GHz, 3.5 GHz and 5.8 GHz ranges.

Mobile Broadband Wireless Access (MBWA) protocols based on standards specifications such as IEEE 802.20 or ATIS/ANSI HC-SDMA (such as iBurst) operate between 1.6 and 2.3 GHz to give mobility and in-building penetration characteristics similar to mobile phones but with vastly greater spectral efficiency.[19]

Some mobile phone networks, like GSM, use the low-microwave/high-UHF frequencies around 1.8 and 1.9 GHz in the Americas and elsewhere, respectively. DVB-SH and S-DMB use 1.452 to 1.492 GHz, while proprietary/incompatible satellite radio in the U.S. uses around 2.3 GHz for DARS.

Microwave radio is used in point-to-point telecommunications transmissions because, due to their short wavelength, highly directional antennas are smaller and therefore more practical than they would be at longer wavelengths (lower frequencies). There is also more bandwidth in the microwave spectrum than in the rest of the radio spectrum; the usable bandwidth below 300 MHz is less than 300 MHz while many GHz can be used above 300 MHz. Typically, microwaves are used in remote broadcasting of news or sports events as the backhaul link to transmit a signal from a remote location to a television station from a specially equipped van. See broadcast auxiliary service (BAS), remote pickup unit (RPU), and studio/transmitter link (STL).

Most satellite communications systems operate in the C, X, Ka, or Ku bands of the microwave spectrum. These frequencies allow large bandwidth while avoiding the crowded UHF frequencies and staying below the atmospheric absorption of EHF frequencies. Satellite TV either operates in the C band for the traditional large dish fixed satellite service or Ku band for direct-broadcast satellite. Military communications run primarily over X or Ku-band links, with Ka band being used for Milstar.

Navigation

Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS) including the Chinese Beidou, the American Global Positioning System (introduced in 1978) and the Russian GLONASS broadcast navigational signals in various bands between about 1.2 GHz and 1.6 GHz.

Radar

Radar is a radiolocation technique in which a beam of radio waves emitted by a transmitter bounces off an object and returns to a receiver, allowing the location, range, speed, and other characteristics of the object to be determined. The short wavelength of microwaves causes large reflections from objects the size of motor vehicles, ships and aircraft. Also, at these wavelengths, the high gain antennas such as parabolic antennas which are required to produce the narrow beamwidths needed to accurately locate objects are conveniently small, allowing them to be rapidly turned to scan for objects. Therefore, microwave frequencies are the main frequencies used in radar. Microwave radar is widely used for applications such as air traffic control, weather forecasting, navigation of ships, and speed limit enforcement. Long-distance radars use the lower microwave frequencies since at the upper end of the band atmospheric absorption limits the range, but millimeter waves are used for short-range radar such as collision avoidance systems.

Radio astronomy

Microwaves emitted by astronomical radio sources; planets, stars, galaxies, and nebulas are studied in radio astronomy with large dish antennas called radio telescopes. In addition to receiving naturally occurring microwave radiation, radio telescopes have been used in active radar experiments to bounce microwaves off planets in the solar system, to determine the distance to the Moon or map the invisible surface of Venus through cloud cover.

A recently[when?] completed microwave radio telescope is the Atacama Large Millimeter Array, located at more than 5,000 meters (16,597 ft) altitude in Chile, which observes the universe in the millimeter and submillimeter wavelength ranges. The world's largest ground-based astronomy project to date, it consists of more than 66 dishes and was built in an international collaboration by Europe, North America, East Asia and Chile.[20][21]

A major recent[when?] focus of microwave radio astronomy has been mapping the cosmic microwave background radiation (CMBR) discovered in 1964 by radio astronomers Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson. This faint background radiation, which fills the universe and is almost the same in all directions, is "relic radiation" from the Big Bang, and is one of the few sources of information about conditions in the early universe. Due to the expansion and thus cooling of the Universe, the originally high-energy radiation has been shifted into the microwave region of the radio spectrum. Sufficiently sensitive radio telescopes can detect the CMBR as a faint signal that is not associated with any star, galaxy, or other object.[22]

Heating and power application

A microwave oven passes microwave radiation at a frequency near 2.45 GHz (12 cm) through food, causing dielectric heating primarily by absorption of the energy in water. Microwave ovens became common kitchen appliances in Western countries in the late 1970s, following the development of less expensive cavity magnetrons. Water in the liquid state possesses many molecular interactions that broaden the absorption peak. In the vapor phase, isolated water molecules absorb at around 22 GHz, almost ten times the frequency of the microwave oven.

Microwave heating is used in industrial processes for drying and curing products.

Many semiconductor processing techniques use microwaves to generate plasma for such purposes as reactive ion etching and plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition (PECVD).

Microwaves are used in stellarators and tokamak experimental fusion reactors to help break down the gas into a plasma and heat it to very high temperatures. The frequency is tuned to the cyclotron resonance of the electrons in the magnetic field, anywhere between 2–200 GHz, hence it is often referred to as Electron Cyclotron Resonance Heating (ECRH). The upcoming ITER thermonuclear reactor[23] will use up to 20 MW of 170 GHz microwaves.

Microwaves can be used to transmit power over long distances, and post-World War 2 research was done to examine possibilities. NASA worked in the 1970s and early 1980s to research the possibilities of using solar power satellite (SPS) systems with large solar arrays that would beam power down to the Earth's surface via microwaves.

Less-than-lethal weaponry exists that uses millimeter waves to heat a thin layer of human skin to an intolerable temperature so as to make the targeted person move away. A two-second burst of the 95 GHz focused beam heats the skin to a temperature of 54 °C (129 °F) at a depth of 0.4 millimetres (1⁄64 in). The United States Air Force and Marines are currently using this type of active denial system in fixed installations.[24]

Spectroscopy

Microwave radiation is used in electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR or ESR) spectroscopy, typically in the X-band region (~9 GHz) in conjunction typically with magnetic fields of 0.3 T. This technique provides information on unpaired electrons in chemical systems, such as free radicals or transition metal ions such as Cu(II). Microwave radiation is also used to perform rotational spectroscopy and can be combined with electrochemistry as in microwave enhanced electrochemistry.

Frequency measurement

Microwave frequency can be measured by either electronic or mechanical techniques.

Frequency counters or high frequency heterodyne systems can be used. Here the unknown frequency is compared with harmonics of a known lower frequency by use of a low-frequency generator, a harmonic generator and a mixer. The accuracy of the measurement is limited by the accuracy and stability of the reference source.

Mechanical methods require a tunable resonator such as an absorption wavemeter, which has a known relation between a physical dimension and frequency.

In a laboratory setting, Lecher lines can be used to directly measure the wavelength on a transmission line made of parallel wires, the frequency can then be calculated. A similar technique is to use a slotted waveguide or slotted coaxial line to directly measure the wavelength. These devices consist of a probe introduced into the line through a longitudinal slot so that the probe is free to travel up and down the line. Slotted lines are primarily intended for measurement of the voltage standing wave ratio on the line. However, provided a standing wave is present, they may also be used to measure the distance between the nodes, which is equal to half the wavelength. The precision of this method is limited by the determination of the nodal locations.

Effects on health

Microwaves are non-ionizing radiation, which means that microwave photons do not contain sufficient energy to ionize molecules or break chemical bonds, or cause DNA damage, as ionizing radiation such as x-rays or ultraviolet can.[25] The word "radiation" refers to energy radiating from a source and not to radioactivity. The main effect of absorption of microwaves is to heat materials; the electromagnetic fields cause polar molecules to vibrate. It has not been shown conclusively that microwaves (or other non-ionizing electromagnetic radiation) have significant adverse biological effects at low levels. Some, but not all, studies suggest that long-term exposure may have a carcinogenic effect.[26]

During World War II, it was observed that individuals in the radiation path of radar installations experienced clicks and buzzing sounds in response to microwave radiation. Research by NASA in the 1970s has shown this to be caused by thermal expansion in parts of the inner ear. In 1955, Dr. James Lovelock was able to reanimate rats chilled to 0 and 1 °C (32 and 34 °F) using microwave diathermy.[27]

When injury from exposure to microwaves occurs, it usually results from dielectric heating induced in the body. The lens and cornea of the eye are especially vulnerable because they contain no blood vessels that can carry away heat. Exposure to microwave radiation can produce cataracts by this mechanism, because the microwave heating denatures proteins in the crystalline lens of the eye[28] (in the same way that heat turns egg whites white and opaque). Exposure to heavy doses of microwave radiation (as from an oven that has been tampered with to allow operation even with the door open) can produce heat damage in other tissues as well, up to and including serious burns that may not be immediately evident because of the tendency for microwaves to heat deeper tissues with higher moisture content.

History

Hertzian optics

Microwaves were first generated in the 1890s in some of the earliest radio wave experiments by physicists who thought of them as a form of "invisible light".[29] James Clerk Maxwell in his 1873 theory of electromagnetism, now called Maxwell's equations, had predicted that a coupled electric field and magnetic field could travel through space as an electromagnetic wave, and proposed that light consisted of electromagnetic waves of short wavelength. In 1888, German physicist Heinrich Hertz was the first to demonstrate the existence of electromagnetic waves, generating radio waves using a primitive spark gap radio transmitter.[30]

Hertz and the other early radio researchers were interested in exploring the similarities between radio waves and light waves, to test Maxwell's theory. They concentrated on producing short wavelength radio waves in the UHF and microwave ranges, with which they could duplicate classic optics experiments in their laboratories, using quasioptical components such as prisms and lenses made of paraffin, sulfur and pitch and wire diffraction gratings, to refract and diffract radio waves like light rays.[31] Hertz produced waves up to 450 MHz; his directional 450 MHz transmitter consisted of a 26 cm brass rod dipole antenna with a spark gap between the ends, suspended at the focal line of a parabolic antenna made of a curved zinc sheet, powered by high voltage pulses from an induction coil.[30] His historic experiments demonstrated that radio waves like light exhibited refraction, diffraction, polarization, interference and standing waves,[31] proving that radio waves and light waves were both forms of Maxwell's electromagnetic waves.

-

Heinrich Hertz's 450 MHz spark transmitter, 1888, consisting of 23 cm dipole and spark gap at focus of parabolic reflector

-

Jagadish Chandra Bose in 1894 was the first person to produce millimeter waves; his spark oscillator (in box, right) generated 60 GHz (5 mm) waves using 3 mm metal ball resonators.

-

Microwave spectroscopy experiment by John Ambrose Fleming in 1897 showing refraction of 1.4 GHz microwaves by paraffin prism, duplicating earlier experiments by Bose and Righi.

-

Augusto Righi's 12 GHz spark oscillator and receiver, 1895

-

3 mm spark ball oscillator Bose used to generate 60 GHz waves

-

Oliver Lodge's 5in oscillator ball he used to generate 1.2 GHz microwaves 1894

-

1.2 GHz microwave spark transmitter (left) and coherer receiver (right) used by Guglielmo Marconi during his 1895 experiments had a range of 6.5 km (4.0 mi)

Beginning in 1894 Indian physicist Jagadish Chandra Bose performed the first experiments with microwaves. He was the first person to produce millimeter waves, generating frequencies up to 60 GHz (5 millimeter) using a 3 mm metal ball spark oscillator.[32][31] Bose also invented waveguide, horn antennas, and semiconductor crystal detectors for use in his experiments. Independently in 1894, Oliver Lodge and Augusto Righi experimented with 1.5 and 12 GHz microwaves respectively, generated by small metal ball spark resonators.[31] Russian physicist Pyotr Lebedev in 1895 generated 50 GHz millimeter waves.[31] In 1897 Lord Rayleigh solved the mathematical boundary-value problem of electromagnetic waves propagating through conducting tubes and dielectric rods of arbitrary shape[33][34][35][36] which gave the modes and cutoff frequency of microwaves propagating through a waveguide.[30]

However, since microwaves were limited to line-of-sight paths, they could not communicate beyond the visual horizon, and the low power of the spark transmitters then in use limited their practical range to a few miles. The subsequent development of radio communication after 1896 employed lower frequencies, which could travel beyond the horizon as ground waves and by reflecting off the ionosphere as skywaves, and microwave frequencies were not further explored at this time.

First microwave communication experiments

Practical use of microwave frequencies did not occur until the 1940s and 1950s due to a lack of adequate sources, since the triode vacuum tube (valve) electronic oscillator used in radio transmitters could not produce frequencies above a few hundred megahertz due to excessive electron transit time and interelectrode capacitance.[30] By the 1930s, the first low-power microwave vacuum tubes had been developed using new principles; the Barkhausen–Kurz tube and the split-anode magnetron.[30] These could generate a few watts of power at frequencies up to a few gigahertz and were used in the first experiments in communication with microwaves.

-

Antennas of 1931 experimental 1.7 GHz microwave relay link across the English Channel

-

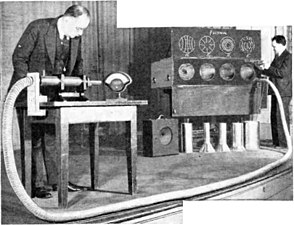

Experimental 3.3 GHz (9 cm) transmitter 1933 at Westinghouse labs [37] transmits voice over a mile.

-

Southworth (at left) demonstrating waveguide at IRE meeting in 1938, showing 1.5 GHz microwaves passing through the 7.5 m flexible metal hose registering on a diode detector

-

The first modern horn antenna in 1938 with inventor Wilmer L. Barrow

In 1931 an Anglo-French consortium headed by Andre C. Clavier demonstrated the first experimental microwave relay link, across the English Channel 40 miles (64 km) between Dover, UK and Calais, France.[38][39] The system transmitted telephony, telegraph and facsimile data over bidirectional 1.7 GHz beams with a power of one-half watt, produced by miniature Barkhausen–Kurz tubes at the focus of 10-foot (3 m) metal dishes.

A word was needed to distinguish these new shorter wavelengths, which had previously been lumped into the "short wave" band, which meant all waves shorter than 200 meters. The terms quasi-optical waves and ultrashort waves were used briefly[37] but did not catch on. The first usage of the word micro-wave apparently occurred in 1931.[39][40]

Radar development

The development of radar, mainly in secrecy, before and during World War II, resulted in the technological advances which made microwaves practical.[30] Microwave wavelengths in the centimeter range were required to give the small radar antennas which were compact enough to fit on aircraft a narrow enough beamwidth to localize enemy aircraft. It was found that conventional transmission lines used to carry radio waves had excessive power losses at microwave frequencies, and George Southworth at Bell Labs and Wilmer Barrow at MIT independently invented waveguide in 1936.[33] Barrow invented the horn antenna in 1938 as a means to efficiently radiate microwaves into or out of a waveguide. In a microwave receiver, a nonlinear component was needed that would act as a detector and mixer at these frequencies, as vacuum tubes had too much capacitance. To fill this need researchers resurrected an obsolete technology, the point contact crystal detector (cat whisker detector) which was used as a demodulator in crystal radios around the turn of the century before vacuum tube receivers.[30][41] The low capacitance of semiconductor junctions allowed them to function at microwave frequencies. The first modern silicon and germanium diodes were developed as microwave detectors in the 1930s, and the principles of semiconductor physics learned during their development led to semiconductor electronics after the war.[30]

-

Randall and Boot's prototype cavity magnetron tube at the University of Birmingham, 1940. In use the tube was installed between the poles of an electromagnet

-

First commercial klystron tube, by General Electric, 1940, sectioned to show internal construction

-

British Mk. VIII, the first microwave air intercept radar, in nose of British fighter

-

Mobile US Army microwave relay station 1945 demonstrating relay systems using frequencies from 100 MHz to 4.9 GHz which could transmit up to 8 phone calls on a beam

The first powerful sources of microwaves were invented at the beginning of World War II: the klystron tube by Russell and Sigurd Varian at Stanford University in 1937, and the cavity magnetron tube by John Randall and Harry Boot at Birmingham University, UK in 1940.[30] Ten centimeter (3 GHz) microwave radar powered by the magnetron tube was in use on British warplanes in late 1941 and proved to be a game changer. Britain's 1940 decision to share its microwave technology with its US ally (the Tizard Mission) significantly shortened the war. The MIT Radiation Laboratory established secretly at Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1940 to research radar, produced much of the theoretical knowledge necessary to use microwaves. The first microwave relay systems were developed by the Allied military near the end of the war and used for secure battlefield communication networks in the European theater.

Post World War II exploitation

After World War II, microwaves were rapidly exploited commercially.[30] Due to their high frequency they had a very large information-carrying capacity (bandwidth); a single microwave beam could carry tens of thousands of phone calls. In the 1950s and 60s transcontinental microwave relay networks were built in the US and Europe to exchange telephone calls between cities and distribute television programs. In the new television broadcasting industry, from the 1940s microwave dishes were used to transmit backhaul video feeds from mobile production trucks back to the studio, allowing the first remote TV broadcasts. The first communications satellites were launched in the 1960s, which relayed telephone calls and television between widely separated points on Earth using microwave beams. In 1964, Arno Penzias and Robert Woodrow Wilson while investigating noise in a satellite horn antenna at Bell Labs, Holmdel, New Jersey discovered cosmic microwave background radiation.

Microwave radar became the central technology used in air traffic control, maritime navigation, anti-aircraft defense, ballistic missile detection, and later many other uses. Radar and satellite communication motivated the development of modern microwave antennas; the parabolic antenna (the most common type), cassegrain antenna, lens antenna, slot antenna, and phased array.

The ability of short waves to quickly heat materials and cook food had been investigated in the 1930s by Ilia E. Mouromtseff at Westinghouse, and at the 1933 Chicago World's Fair demonstrated cooking meals with a 60 MHz radio transmitter.[42] In 1945 Percy Spencer, an engineer working on radar at Raytheon, noticed that microwave radiation from a magnetron oscillator melted a candy bar in his pocket. He investigated cooking with microwaves and invented the microwave oven, consisting of a magnetron feeding microwaves into a closed metal cavity containing food, which was patented by Raytheon on 8 October 1945. Due to their expense microwave ovens were initially used in institutional kitchens, but by 1986 roughly 25% of households in the U.S. owned one. Microwave heating became widely used as an industrial process in industries such as plastics fabrication, and as a medical therapy to kill cancer cells in microwave hyperthermy.

The traveling wave tube (TWT) developed in 1943 by Rudolph Kompfner and John Pierce provided a high-power tunable source of microwaves up to 50 GHz and became the most widely used microwave tube (besides the ubiquitous magnetron used in microwave ovens). The gyrotron tube family developed in Russia could produce megawatts of power up into millimeter wave frequencies and is used in industrial heating and plasma research, and to power particle accelerators and nuclear fusion reactors.

Solid state microwave devices

The development of semiconductor electronics in the 1950s led to the first solid state microwave devices which worked by a new principle; negative resistance (some of the prewar microwave tubes had also used negative resistance).[30] The feedback oscillator and two-port amplifiers which were used at lower frequencies became unstable at microwave frequencies, and negative resistance oscillators and amplifiers based on one-port devices like diodes worked better.

The tunnel diode invented in 1957 by Japanese physicist Leo Esaki could produce a few milliwatts of microwave power. Its invention set off a search for better negative resistance semiconductor devices for use as microwave oscillators, resulting in the invention of the IMPATT diode in 1956 by W.T. Read and Ralph L. Johnston and the Gunn diode in 1962 by J. B. Gunn.[30] Diodes are the most widely used microwave sources today.

Two low-noise solid state negative resistance microwave amplifiers were developed; the maser invented in 1953 by Charles H. Townes, James P. Gordon, and H. J. Zeiger, and the varactor parametric amplifier developed in 1956 by Marion Hines.[30] The parametric amplifier and the ruby maser, invented in 1958 by a team at Bell Labs headed by H.E.D. Scovil were used for low noise microwave receivers in radio telescopes and satellite ground stations. The maser led to the development of atomic clocks, which keep time using a precise microwave frequency emitted by atoms undergoing an electron transition between two energy levels. Negative resistance amplifier circuits required the invention of new nonreciprocal waveguide components, such as circulators, isolators, and directional couplers. In 1969 Kaneyuki Kurokawa derived mathematical conditions for stability in negative resistance circuits which formed the basis of microwave oscillator design.[43]

Microwave integrated circuits

Prior to the 1970s microwave devices and circuits were bulky and expensive, so microwave frequencies were generally limited to the output stage of transmitters and the RF front end of receivers, and signals were heterodyned to a lower intermediate frequency for processing. The period from the 1970s to the present has seen the development of tiny inexpensive active solid-state microwave components which can be mounted on circuit boards, allowing circuits to perform significant signal processing at microwave frequencies. This has made possible satellite television, cable television, GPS devices, and modern wireless devices, such as smartphones, Wi-Fi, and Bluetooth which connect to networks using microwaves.

Microstrip, a type of transmission line usable at microwave frequencies, was invented with printed circuits in the 1950s.[30] The ability to cheaply fabricate a wide range of shapes on printed circuit boards allowed microstrip versions of capacitors, inductors, resonant stubs, splitters, directional couplers, diplexers, filters and antennas to be made, thus allowing compact microwave circuits to be constructed.[30]

Transistors that operated at microwave frequencies were developed in the 1970s. The semiconductor gallium arsenide (GaAs) has a much higher electron mobility than silicon,[30] so devices fabricated with this material can operate at 4 times the frequency of similar devices of silicon. Beginning in the 1970s GaAs was used to make the first microwave transistors,[30] and it has dominated microwave semiconductors ever since. MESFETs (metal-semiconductor field-effect transistors), fast GaAs field effect transistors using Schottky junctions for the gate, were developed starting in 1968 and have reached cutoff frequencies of 100 GHz, and are now the most widely used active microwave devices.[30] Another family of transistors with a higher frequency limit is the HEMT (high electron mobility transistor), a field effect transistor made with two different semiconductors, AlGaAs and GaAs, using heterojunction technology, and the similar HBT (heterojunction bipolar transistor).[30]

GaAs can be made semi-insulating, allowing it to be used as a substrate on which circuits containing passive components, as well as transistors, can be fabricated by lithography.[30] By 1976 this led to the first integrated circuits (ICs) which functioned at microwave frequencies, called monolithic microwave integrated circuits (MMIC).[30] The word "monolithic" was added to distinguish these from microstrip PCB circuits, which were called "microwave integrated circuits" (MIC). Since then, silicon MMICs have also been developed. Today MMICs have become the workhorses of both analog and digital high-frequency electronics, enabling the production of single-chip microwave receivers, broadband amplifiers, modems, and microprocessors.

See also

- Block upconverter (BUC)

- Cosmic microwave background

- Electron cyclotron resonance

- International Microwave Power Institute

- Low-noise block converter (LNB)

- Maser

- Microwave auditory effect

- Microwave cavity

- Microwave chemistry

- Microwave radio relay

- Microwave transmission

- Rain fade

- RF switch matrix

- The Thing (listening device)

References

- ^ a b Hitchcock, R. Timothy (2004). Radio-frequency and Microwave Radiation. American Industrial Hygiene Assn. p. 1. ISBN 978-1931504553.

- ^ a b Kumar, Sanjay; Shukla, Saurabh (2014). Concepts and Applications of Microwave Engineering. PHI Learning Pvt. Ltd. ISBN 978-8120349353.

- ^ Jones, Graham A.; Layer, David H.; Osenkowsky, Thomas G. (2013). National Association of Broadcasters Engineering Handbook, 10th Ed. Focal Press. p. 6. ISBN 978-1136034107.

- ^ Pozar, David M. (1993). Microwave Engineering Addison–Wesley Publishing Company. ISBN 0-201-50418-9.

- ^ Sorrentino, R. and Bianchi, Giovanni (2010) Microwave and RF Engineering, John Wiley & Sons, p. 4, ISBN 047066021X.

- ^ "Electromagnetic radiation - Microwaves, Wavelengths, Frequency | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2023-08-15.

- ^ "Details for IEV number 713-06-03: "microwave"". International Electrotechnical Vocabulary (in Japanese). Retrieved 2024-03-27.

- ^ "Details for IEV number 701-02-12: "radio wave"". International Electrotechnical Vocabulary (in Japanese). Retrieved 2024-03-27.

- ^ "Frequency Letter bands". Microwave Encyclopedia. Microwaves101 website, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE). 14 May 2016. Retrieved 1 July 2018.

- ^ Golio, Mike; Golio, Janet (2007). RF and Microwave Applications and Systems. CRC Press. pp. 1.9 – 1.11. ISBN 978-1420006711.

- ^ See "eEngineer – Radio Frequency Band Designations". Radioing.com. Retrieved 2011-11-08., PC Mojo – Webs with MOJO from Cave Creek, AZ (2008-04-25). "Frequency Letter bands – Microwave Encyclopedia". Microwaves101.com. Archived from the original on 2014-07-14. Retrieved 2011-11-08., Letter Designations of Microwave Bands.

- ^ Skolnik, Merrill I. (2001) Introduction to Radar Systems, Third Ed., p. 522, McGraw Hill. 1962 Edition full text

- ^ a b Seybold, John S. (2005). Introduction to RF Propagation. John Wiley and Sons. pp. 55–58. ISBN 978-0471743682.

- ^ a b Golio, Mike; Golio, Janet (2007). RF and Microwave Passive and Active Technologies. CRC Press. pp. I.2 – I.4. ISBN 978-1420006728.

- ^ Karmel, Paul R.; Colef, Gabriel D.; Camisa, Raymond L. (1998). Introduction to Electromagnetic and Microwave Engineering. John Wiley and Sons. p. 1. ISBN 9780471177814.

- ^ Microwave Oscillator Archived 2013-10-30 at the Wayback Machine notes by Herley General Microwave

- ^ a b Sisodia, M. L. (2007). Microwaves : Introduction To Circuits, Devices And Antennas. New Age International. pp. 1.4 – 1.7. ISBN 978-8122413380.

- ^ Liou, Kuo-Nan (2002). An introduction to atmospheric radiation. Academic Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-12-451451-5. Retrieved 12 July 2010.

- ^ "IEEE 802.20: Mobile Broadband Wireless Access (MBWA)". Official web site. Retrieved August 20, 2011.

- ^ "ALMA website". Retrieved 2011-09-21.

- ^ "Welcome to ALMA!". Retrieved 2011-05-25.

- ^ Wright, E.L. (2004). "Theoretical Overview of Cosmic Microwave Background Anisotropy". In W. L. Freedman (ed.). Measuring and Modeling the Universe. Carnegie Observatories Astrophysics Series. Cambridge University Press. p. 291. arXiv:astro-ph/0305591. Bibcode:2004mmu..symp..291W. ISBN 978-0-521-75576-4.

- ^ "The way to new energy". ITER. 2011-11-04. Retrieved 2011-11-08.

- ^ Silent Guardian Protection System. Less-than-Lethal Directed Energy Protection. raytheon.com

- ^ Nave, Rod. "Interaction of Radiation with Matter". HyperPhysics. Retrieved 20 October 2014.

- ^ Goldsmith, JR (December 1997). "Epidemiologic evidence relevant to radar (microwave) effects". Environmental Health Perspectives. 105 (Suppl. 6): 1579–1587. doi:10.2307/3433674. JSTOR 3433674. PMC 1469943. PMID 9467086.

- ^ Andjus, R.K.; Lovelock, J.E. (1955). "Reanimation of rats from body temperatures between 0 and 1 °C by microwave diathermy". The Journal of Physiology. 128 (3): 541–546. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1955.sp005323. PMC 1365902. PMID 13243347.

- ^ Lipman, Richard M.; Tripathi, Brenda J.; Tripathi, Ramesh C. (November–December 1988). "Cataracts Induced by Microwave and Ionizing Radiation". Survey of Ophthalmology. 33 (3): 206–207. doi:10.1016/0039-6257(88)90088-4. PMID 3068822.

- ^ Hong, Sungook (2001). Wireless: From Marconi's Black-box to the Audion. MIT Press. pp. 5–9, 22. ISBN 978-0262082983.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Roer, T.G. (2012). Microwave Electronic Devices. Springer Science and Business Media. pp. 1–12. ISBN 978-1461525004.

- ^ a b c d e Sarkar, T. K.; Mailloux, Robert; Oliner, Arthur A. (2006). History of Wireless. John Wiley and Sons. pp. 474–486. ISBN 978-0471783015.

- ^ Emerson, D.T. (February 1998). "The work of Jagdish Chandra Bose: 100 years of MM-wave research". National Radio Astronomy Observatory.

- ^ a b Packard, Karle S. (September 1984). "The Origin of Waveguides: A Case of Multiple Rediscovery" (PDF). IEEE Transactions on Microwave Theory and Techniques. MTT-32 (9): 961–969. Bibcode:1984ITMTT..32..961P. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.532.8921. doi:10.1109/tmtt.1984.1132809. Retrieved March 24, 2015.

- ^ Strutt, William (Lord Rayleigh) (February 1897). "On the passage of electric waves through tubes, or the vibrations of dielectric cylinders". Philosophical Magazine. 43 (261): 125–132. doi:10.1080/14786449708620969.

- ^ Kizer, George (2013). Digital Microwave Communication: Engineering Point-to-Point Microwave Systems. John Wiley and Sons. p. 7. ISBN 978-1118636800.

- ^ Lee, Thomas H. (2004). Planar Microwave Engineering: A Practical Guide to Theory, Measurement, and Circuits, Vol. 1. Cambridge University Press. pp. 18, 118. ISBN 978-0521835268.

- ^ a b Mouromtseff, Ilia A. (September 1933). "3 1/2 Inch Waves Now Practical" (PDF). Short Wave Craft. 4 (5). New York: Popular Book Corp.: 266–267.

- ^ "Microwaves span the English Channel" (PDF). Short Wave Craft. Vol. 6, no. 5. New York: Popular Book Co. September 1935. pp. 262, 310. Retrieved March 24, 2015.

- ^ a b Free, E.E. (August 1931). "Searchlight radio with the new 7 inch waves" (PDF). Radio News. Vol. 8, no. 2. New York: Radio Science Publications. pp. 107–109. Retrieved March 24, 2015.

- ^ Ayto, John (2002). 20th century words. Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press. p. 269. ISBN 978-7560028743.

- ^ Riordan, Michael; Lillian Hoddeson (1988). Crystal fire: the invention of the transistor and the birth of the information age. US: W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 89–92. ISBN 978-0-393-31851-7.

- ^ "Cooking with Short Waves" (PDF). Short Wave Craft. 4 (7): 394. November 1933. Retrieved 23 March 2015.

- ^ Kurokawa, Kaneyuki (July 1969). "Some Basic Characteristics of Broadband Negative Resistance Oscillator Circuits". Bell System Tech. J. 48 (6): 1937–1955. doi:10.1002/j.1538-7305.1969.tb01158.x. Retrieved December 8, 2012.

External links

- EM Talk, Microwave Engineering Tutorials and Tools

- Millimeter Wave Archived 2013-06-09 at the Wayback Machine and Microwave Waveguide dimension chart.

![Experimental 3.3 GHz (9 cm) transmitter 1933 at Westinghouse labs [37] transmits voice over a mile.](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/da/Experimental_Westinghouse_3GHz_microwave_transmitter_1933.jpg/245px-Experimental_Westinghouse_3GHz_microwave_transmitter_1933.jpg)