Eartha Kitt

Eartha Kitt | |

|---|---|

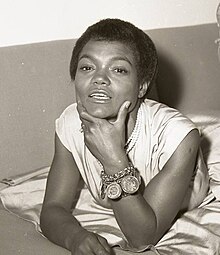

Kitt in 1957 | |

| Born | Eartha Mae Keith January 17, 1927 |

| Died | December 25, 2008 (aged 81) Weston, Connecticut, U.S. |

| Other names | Mother Eartha,[3] Kitty |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1942–2008 |

| Spouse |

John W. McDonald

(m. 1960; div. 1964) |

| Children | 1 |

| Musical career | |

| Genres | |

| Labels |

|

| Website | earthakitt |

Eartha Mae Kitt (née Keith; January 17, 1927 – December 25, 2008) was an American singer and actress. She was known for her highly distinctive singing style and her 1953 recordings of "C'est si bon" and the Christmas novelty song "Santa Baby".

Kitt began her career in 1942 and appeared in the 1945 original Broadway theatre production of the musical Carib Song. In the early 1950s, Kitt had six US Top 30 entries, including "Uska Dara" (1953) and "I Want to Be Evil" (1953). Her other recordings include the UK Top 10 song "Under the Bridges of Paris" (1954), "Just an Old Fashioned Girl" (1956) and "Where Is My Man" (1983). Orson Welles once called her the "most exciting woman in the world".[4] Kitt starred as Catwoman in the third and final season of the television series Batman in 1967.

In 1968, Kitt's career in the U.S. deteriorated after she made anti-Vietnam War statements at a White House luncheon. Ten years later, Kitt made a successful return to Broadway in the 1978 original production of the musical Timbuktu!, for which she received the first of her two Tony Award nominations. Kitt's second was for the 2000 original production of the musical The Wild Party. Kitt wrote three autobiographies.[5]

Kitt found a new generation of fans through her various voice acting roles in the last decade of her life. She voiced the villains Yzma and Vexus in The Emperor's New Groove franchise and My Life As A Teenage Robot, with the former earning her two Daytime Emmy Awards. Kitt posthumously won a third Emmy in 2010 for her guest performance on Wonder Pets!.

Early life

[edit]Eartha Mae Keith was born in the small town of North, South Carolina,[6][7] on January 17, 1927.[6][8] Her mother, Annie Mae Keith (later Annie Mae Riley), was of Cherokee and African descent. Though she had little knowledge of her father, it was reported that he was the son of the owner of the plantation where she had been born, and that Kitt was conceived by rape.[8][9][10] In a 2013 biography, British journalist John Williams claimed that Kitt's father was a white man, a local doctor named Daniel Sturkie.[11] Kitt's daughter, Kitt McDonald Shapiro, has questioned the accuracy of the claim.[12]

Eartha's mother soon went to live with a black man who refused to accept Eartha because of her relatively pale complexion. Kitt was raised by a relative named Aunt Rosa, in whose household she was abused. After the death of Annie Mae, Eartha was sent to live with another close relative named Mamie Kitt (who Eartha later came to believe was her biological mother) in Harlem, New York City,[8] where Eartha attended the Metropolitan Vocational High School (later renamed the High School of Performing Arts).[13]

Career

[edit]

Kitt began her career as a member of the Katherine Dunham Company in 1943 and remained a member of the troupe until 1948. A talented singer with a distinctive voice, Kitt recorded the hits "Let's Do It", "Champagne Taste", "C'est si bon" (which Stan Freberg famously burlesqued), "Just an Old Fashioned Girl", "Monotonous", "Je cherche un homme", "Love for Sale", "I'd Rather Be Burned as a Witch", "Kâtibim" (a Turkish melody), "Mink, Schmink", "Under the Bridges of Paris", and her most recognizable hit "Santa Baby", which was released in 1953. Kitt's unique style was enhanced as she became fluent in French during her years performing in Europe. Kitt spoke four languages and sang in 11, which she demonstrated in many of the live recordings of her cabaret performances.[14]

Career peaks

[edit]

In 1950, Orson Welles gave Kitt her first starring role as Helen of Troy in his staging of Dr. Faustus. Two years later, Kitt was cast in the revue New Faces of 1952, introducing "Monotonous" and "Bal, Petit Bal", two songs with which she is still identified. In 1954, 20th Century-Fox distributed an independently filmed version of the revue entitled New Faces, in which Kitt performed "Monotonous", "Uska Dara", "C'est si bon",[15] and "Santa Baby". Though it is often alleged that Welles and Kitt had an affair during her 1957 run in Shinbone Alley, Kitt categorically denied this in a June 2001 interview with George Wayne of Vanity Fair. "I never had sex with Orson Welles," Kitt told Vanity Fair: "It was a working situation and nothing else."[16] Her other films in the 1950s included The Mark of the Hawk (1957), St. Louis Blues (1958) and Anna Lucasta (1958).

Throughout the rest of the 1950s and early 1960s, Kitt recorded; worked in film, television, and nightclubs; and returned to the Broadway stage, in Mrs. Patterson (during the 1954–1955 season), Shinbone Alley (in 1957), and the short-lived Jolly's Progress (in 1959).[17] In 1964, Kitt helped open the Circle Star Theater in San Carlos, California. In the late 1960s, Batman featured Kitt as Catwoman after Julie Newmar had left the show in 1967. She appeared in a 1967 Mission: Impossible episode "The Traitor", as Tina Mara, a contortionist.

In 1956, Kitt published an autobiography called Thursday's Child, which would later serve as inspiration for the name of the 1999 David Bowie song "Thursday's Child".[18][19]

The "White House Incident"

[edit]On 18 January 1968[20][21] during Lyndon B. Johnson's administration, Kitt encountered a substantial professional setback after she made anti-war statements during a White House luncheon.[22][23] Kitt was asked by First Lady Lady Bird Johnson about the Vietnam War. She replied: "You send the best of this country off to be shot and maimed. No wonder the kids rebel and take pot."[14] During a question-and-answer session, Kitt stated:

The children of America are not rebelling for no reason. They are not hippies for no reason at all. We don't have what we have on Sunset Blvd. for no reason. They are rebelling against something. There are so many things burning the people of this country, particularly mothers. They feel they are going to raise sons – and I know what it's like, and you have children of your own, Mrs. Johnson – we raise children and send them to war.[24][25]

Kitt's remarks reportedly caused Mrs. Johnson to burst into tears.[9] It is widely believed[26] that Kitt's career in the United States was ended following her comments about the Vietnam War,[27][28] after which she was branded "a sadistic nymphomaniac" by the CIA.[12] A CIA dossier about Kitt was discovered by Seymour Hersh in 1975. Hersh published an article about the dossier in The New York Times.[29] The dossier contained comments about Kitt's sex life and family history, along with negative opinions of her that were held by former colleagues. Kitt's response to the dossier was to say: "I don't understand what this is about. I think it's disgusting."[29] Following the incident, Kitt devoted her energies to performances in Europe and Asia.[30]

In February 2022, Catwoman vs. the White House,[31][32] The New Yorker short documentary, directed by Scott Calonico used photos, clippings and footage to show how Kitt disrupted the White House luncheon, taking Lyndon B. Johnson to task.[33]

Kitt would later return to the White House on 29 January 1978 after accepting an invitation from U.S. President Jimmy Carter to attend a reception honoring the 10th anniversary of the reopening of Ford's Theatre.[34]

Broadway

[edit]In the 1970s, Kitt appeared on television several times on BBC's long-running variety show The Good Old Days, and in 1987 took over from fellow American Dolores Gray in the London West End production of Stephen Sondheim's Follies and returned at the end of that run to star in a one-woman-show at the same Shaftesbury Theatre, both to tremendous acclaim. In both those shows, Kitt performed the show-stopping theatrical anthem "I'm Still Here". Kitt returned to New York City in a triumphant turn in the Broadway spectacle Timbuktu! (a version of the perennial Kismet, set in Africa) in 1978. In the musical, one song gives a "recipe" for mahoun, a preparation of cannabis, in which her sultry purring rendition of the refrain "constantly stirring with a long wooden spoon" was distinctive.[citation needed] Kitt was nominated for the Tony Award for Best Actress in a Musical for her performance. In the late 1990s, Kitt appeared as the Wicked Witch of the West in the North American national touring company of The Wizard of Oz.[35] In 2000, she again returned to Broadway in the short-lived run of Michael John LaChiusa's The Wild Party. Beginning in late 2000, Kitt starred as the Fairy Godmother in the U.S. national tour of Cinderella.[36] In 2003, she replaced Chita Rivera in Nine. Kitt reprised her role as the Fairy Godmother at a special engagement of Cinderella, which took place at Lincoln Center during the holiday season of 2004.[37] From October to early December 2006, Kitt co-starred in the off-Broadway musical Mimi le Duck.

Voice-over

[edit]In 1978, Kitt did the voice-over in a television commercial for the album Aja by the rock group Steely Dan. In 1988, she voiced Vietnam After The Fire. a British documentary which looked at the legacy left to the Vietnamese people after the devastation of the war and showed the effects of bombings and defoliants on farmland and forests 13 years after the war ended.[38] One of Kitt's more unusual roles was as Kaa in a 1994 BBC Radio adaptation of The Jungle Book. In 1998, she voiced Bagheera in the live-action direct-to-video Disney film The Jungle Book: Mowgli's Story. Kitt also lent her distinctive voice to Yzma in The Emperor's New Groove (for which she won her first Annie Award) and reprised her role in Kronk's New Groove and The Emperor's New School, for which Kitt won two Emmy Awards and, in 2007–08, two more Annie Awards for Voice Acting in an Animated Television Production. From 2002 to 2006, she also voiced the villain Vexus in the Nickelodeon series My Life as a Teenage Robot.

Later years

[edit]1980s

[edit]In 1984, Kitt returned to the music charts with a disco song titled "Where Is My Man", the first certified gold record of her career. "Where Is My Man" reached the Top 40 on the UK Singles Chart, where it peaked at No. 36;[39] the song became a standard in discos and dance clubs of the time and made the Top 10 on the US Billboard dance chart, where it reached No. 7.[40] The single was followed by the album I Love Men on the Record Shack label. Kitt found new audiences in nightclubs across the UK and the United States, including a whole new generation of gay male fans, and she responded by frequently giving benefit performances in support of HIV/AIDS organizations. Kitt's 1989 follow-up hit "Cha-Cha Heels" (featuring Bronski Beat), which was originally intended to be recorded by Divine, received a positive response from UK dance clubs, reaching No. 32 in the charts in that country. In 1988, Kitt replaced Dolores Gray in the West End production of Stephen Sondheim's Follies as Carlotta, receiving standing ovations every night for her rendition of "I'm Still Here" at the beginning of act 2. Kitt went on to perform her own one-woman show at the Shaftesbury Theatre to sold-out houses for three weeks in early 1989 after Follies.

1990s

[edit]Kitt appeared with Jimmy James and George Burns at a fundraiser in 1990 produced by Scott Sherman, an agent from the Atlantic Entertainment Group. It was arranged that James would impersonate Kitt and then Kitt would walk out to take the microphone. This was met with a standing ovation.[41] In 1991, Kitt returned to the screen in Ernest Scared Stupid as Old Lady Hackmore. In 1992, she had a supporting role as Lady Eloise in Boomerang. In 1995, Kitt appeared as herself in an episode of The Nanny, where she performed a song in French and flirted with Maxwell Sheffield (Charles Shaughnessy). In November 1996, Kitt appeared in an episode of Celebrity Jeopardy!. She also did a series of commercials for Old Navy.

2000s

[edit]In 2000, Kitt won an Annie Award for her starring voice role as Yzma in the Disney feature film The Emperor's New Groove, later reprising the role in 2005 in Disney's Kronk's New Groove. Kitt returned once again to the silver screen in 2003 with the charming role of Madame Zeroni in the film Holes based on the book by the same name, by author Louis Sachar. In August 2007, Kitt was the spokesperson for MAC Cosmetics' Smoke Signals collection. She re-recorded "Smoke Gets in Your Eyes" for the occasion, was showcased on the MAC website, and the song was played at all MAC locations carrying the collection for the month. Kitt also appeared in the 2007 independent film And Then Came Love opposite Vanessa Williams. In her later years, Kitt made annual appearances in the New York Manhattan cabaret scene at venues such as the Ballroom and the Café Carlyle.[14] As noted, Kitt did voice work for the animated projects The Emperor's New Groove and its spinoffs, as well as for My Life as a Teenage Robot. In April 2008, just months before her death, Kitt appeared at the Cheltenham Jazz Festival; the performance was recorded.[citation needed] Kitt voiced herself in The Simpsons episode "Once Upon a Time in Springfield", where she is depicted as a former lover of Krusty the Clown.

Personal life

[edit]

Kitt married John William McDonald, an associate of a real estate investment company, on June 9, 1960.[42] Their daughter, Kitt McDonald, was born on November 26, 1961 and was baptized Catholic at Blessed Sacrament Catholic Church.[43] Eartha Kitt and McDonald separated on July 1, 1963, and divorced on March 26, 1964.[44]

A longtime Connecticut resident, Kitt lived in a converted barn on a sprawling farm in the Merryall section of New Milford for many years and was active in local charities and causes throughout Litchfield County. She later moved to Pound Ridge, New York, but returned in 2002 to the southern Fairfield County, Connecticut town of Weston, in order to be near her daughter Kitt and family. Her daughter, Kitt, married Charles Lawrence Shapiro in 1987.[45]

Activism

[edit]Kitt was active in numerous social causes in the 1950s and 1960s. In 1966, she established the Kittsville Youth Foundation, a chartered and non-profit organization for underprivileged youths in the Watts area of Los Angeles.[46] Kitt was also involved with a group of youths in the area of Anacostia in Washington, D.C., who called themselves "Rebels with a Cause". She supported the group's efforts to clean up streets and establish recreation areas in an effort to keep them out of trouble by testifying with them before the House General Subcommittee on Education of the Committee on Education and Labor. In her testimony, in May 1967, Kitt stated that the Rebels' "achievements and accomplishments should certainly make the adult 'do-gooders' realize that these young men and women have performed in 1 short year – with limited finances – that which was not achieved by the same people who might object to turning over some of the duties of planning, rehabilitation, and prevention of juvenile delinquents and juvenile delinquency to those who understand it and are living it". Kitt added that "the Rebels could act as a model for all urban areas throughout the United States with similar problems".[47] "Rebels with a Cause" subsequently received the needed funding.[48] Kitt was also a member of the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom; her criticism of the Vietnam War and its connection to poverty and racial unrest in 1968 can be seen as part of a larger commitment to peace activism.[49] Like many politically active public figures of her time, Kitt was under surveillance by the CIA, beginning in 1956. After The New York Times discovered the CIA file on Kitt in 1975, she granted the paper permission to print portions of the report, stating: "I have nothing to be afraid of and I have nothing to hide."[29]

Kitt later became a vocal advocate for LGBT rights and publicly supported same-sex marriage, which she considered a civil right. She had been quoted as saying: "I support it [gay marriage] because we're asking for the same thing. If I have a partner and something happens to me, I want that partner to enjoy the benefits of what we have reaped together. It's a civil-rights thing, isn't it?"[50] Kitt famously appeared at many LGBT fundraisers, including a mega event in Baltimore, Maryland, with George Burns and Jimmy James.[41] Scott Sherman, an agent at Atlantic Entertainment Group, stated: "Eartha Kitt is fantastic... appears at so many LGBT events in support of civil rights." In a 1992 interview with Dr. Anthony Clare, Kitt spoke about her gay following, saying:

We're all rejected people, we know what it is to be refused, we know what it is to be oppressed, depressed, and then, accused, and I am very much cognizant of that feeling. Nothing in the world is more painful than rejection. I am a rejected, oppressed person, and so I understand them, as best as I can, even though I am a heterosexual.[51]

Death

[edit]Kitt died of colon cancer on Christmas Day 2008 at her home in Weston, Connecticut; she was 81 years old.[7][52][53] Her daughter, Kitt McDonald, described her last days with her mother:

I was with her when she died. She left this world literally screaming at the top of her lungs. I was with her constantly, she lived not even 3 miles from my house, we were together practically every day. She was home for the last few weeks when the doctor told us there was nothing they could do any more. Up until the last two days, she was still moving around. The doctor told us she will leave very quickly and her body will just start to shut down. But when she left, she left the world with a bang, she left it how she lived it. She screamed her way out of here, literally. I truly believe her survival instincts were so part of her DNA that she was not going to go quietly or willingly. It was just the two of us hanging out [during the last days] she was very funny. We didn't have to [talk] because I always knew how she felt about me. I was the love of her life, so the last part of her life we didn't have to have these heart to heart talks. She started to see people that weren't there. She thought I could see them too, but, of course, I couldn't. I would make fun of her like, "I'm going to go in the other room and you stay here and talk to your friends."[54]

Discography

[edit]- Studio albums

- RCA Victor Presents Eartha Kitt (1953)

- That Bad Eartha (1954)

- Down to Eartha (1955)

- That Bad Eartha (1956)

- Thursday's Child (1957)

- St. Louis Blues (1958)

- The Fabulous Eartha (1959)

- Revisited (1960)

- Bad But Beautiful (1962)

- The Romantic Eartha (1962)

- Love for Sale (1965)

- Canta en Castellano (1965)

- Sentimental Eartha (1970)

- I Love Men (1984)

- I'm Still Here (1989)

- Thinking Jazz (1991)

- Back in Business (1994)

Filmography

[edit]Film

[edit]| Year | Film | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1948 | Casbah | Uncredited | |

| 1951 | Parigi è sempre Parigi | Herself | |

| 1954 | New Faces | ||

| 1957 | The Mark of the Hawk | Renee | |

| 1958 | St. Louis Blues | Gogo Germaine | |

| 1958 | Anna Lucasta | Anna Lucasta | |

| 1961 | Saint of Devil's Island | Annette | |

| 1965 | Uncle Tom's Cabin | Singer | Uncredited role |

| Synanon | Betty | ||

| 1971 | Up the Chastity Belt | Scheherazade | |

| 1975 | Friday Foster | Madame Rena | |

| 1979 | Butterflies in Heat | Lola | |

| 1985 | The Serpent Warriors | Snake Priestess | |

| 1987 | Master of Dragonard Hill | Naomi | |

| Dragonard | Naomi | ||

| The Pink Chiquitas | Betty / The Meteor (voice) | ||

| 1989 | Erik the Viking | Freya | |

| 1990 | Living Doll | Mrs. Swartz | |

| 1991 | Ernest Scared Stupid | Old Lady Hackmore | |

| 1992 | Boomerang | Lady Eloise | |

| 1993 | Fatal Instinct | First Trial Judge | |

| 1996 | Harriet the Spy | Agatha K. Plummer | |

| 1997 | Ill Gotten Gains | The Wood (Voice) | |

| 1998 | I Woke Up Early the Day I Died | Cult Leader | |

| The Jungle Book: Mowgli's Story | Bagheera (voice) | [55] | |

| 2000 | The Emperor's New Groove | Yzma (voice) | [55] |

| 2002 | Anything But Love | Herself | |

| 2003 | Holes | Madame Zeroni | |

| 2005 | Preaching to the Choir | Ms. Nettie | |

| Kronk's New Groove | Yzma (voice) | Direct-to-video[55] | |

| 2007 | And Then Came Love | Mona |

Television

[edit]| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1952–1963 | The Ed Sullivan Show | Herself | 15 episodes |

| 1963–1978 | The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson | Herself | 8 episodes |

| 1964–1979 | The Mike Douglas Show | Herself | 16 episodes |

| 1965 | I Spy | Angel | Episode: "The Loser" Nominated–Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Single Performance by an Actress in a Leading Role in a Drama |

| 1965 | The Eartha Kitt Show | Herself | |

| 1967 | Mission: Impossible | Tina Maria | Episode: "The Traitor" |

| 1967–1968 | Batman | Selina Kyle / Catwoman | 5 episodes |

| 1969 | The Dick Cavett Show | Herself | 1 episode |

| 1972 | Lieutenant Schuster's Wife | Lady | Television film |

| 1973–1978 | The Merv Griffin Show | Herself | 3 episodes |

| 1974 | The Protectors | Carrie Blaine | Episode: "A Pocketful of Posies" |

| 1978 | Police Woman | Amelia | Episode: "Tigress" |

| To Kill a Cop | Paula | Television film | |

| 1983 | A Night on the Town | Unknown role | Television film |

| 1985 | Miami Vice | Santería Priestess Chata | Episode: "Whatever Works" |

| 1989 | After Dark | Herself | Episode: "Rock Bottom?" Extended appearance on British discussion programme, together with Simon Napier-Bell and Pat Kane among others |

| 1993 | Jack's Place | Isabel Lang | Episode: "The Seventh Meal" |

| Matrix | Sister Rowena | Episode: "Moths to a Flame" | |

| 1994 | Space Ghost Coast to Coast | Herself | Episode: "Batmantis" |

| 1995 | The Magic School Bus | Mrs. Franklin (voice) | Episode: "Going Batty"[55] |

| New York Undercover | Mrs. Stubbs | Episode: "Student Affairs" | |

| Living Single | Jacqueline Richards | Episode: "He Works Hard for the Money" Nominated–NAACP Image Award for Outstanding Supporting Actress in a Comedy Series | |

| 1996 | The Nanny | Herself | Episode: "A Pup in Paris" |

| 1997 | The Chris Rock Show | Herself | 1 episode |

| 1997–2000 | The Rosie O'Donnell Show | Herself | 2 episodes |

| 1998 | The Wild Thornberrys | Lioness #1 (voice) | Episode: "Flood Warning"[55] |

| 1999 | The Famous Jett Jackson | Albertine Whethers | Episode: "Field of Dweebs" |

| 2000 | Happily Ever After: Fairy Tales for Every Child | The Snow Queen (voice) | Episode: "The Snow Queen" |

| Welcome to New York | June | 2 episodes | |

| 2001 | The Feast of All Saints | Lola Dede | Television film |

| Santa, Baby! | Emerald (voice) | Television film[55] | |

| 2002–2006 | My Life as a Teenage Robot | Queen Vexus (voice) | 7 episodes[55] |

| 2003 | Hollywood Squares | Herself | 5 episodes |

| 2005 | Larry King Live | Herself | 2 episodes |

| 2006–2008 | The Emperor's New School | Yzma (voice) | Annie Award for Best Voice Acting in an Animated Television Production (2007–2008) Daytime Emmy Award for Outstanding Performer in an Animated Program (2007–2008) |

| 2007 | American Dad! | Fortune Teller (voice) | Episode: "Dope and Faith" |

| 2008 | An Evening with Eartha Kitt | Herself | Hosted by Gwen Ifill for PBS |

| 2009 | Wonder Pets! | Cool Cat (voice) | Episode: "Save the Cool Cat and the Hip Hippo" Aired posthumously Daytime Emmy Award for Outstanding Performer in an Animated Program |

| 2010 | The Simpsons | Herself (voice) | "Once Upon a Time in Springfield" Aired posthumously |

Documentary

[edit]| Year | Film | Role |

|---|---|---|

| 1982 | All by Myself: The Eartha Kitt Story | Herself |

| 1995 | Unzipped | |

| 2002 | The Making and Meaning of We Are Family | |

| The Sweatbox (unreleased) |

Stage work

[edit]| Year | Title | Location | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1945 | Blue Holiday | Broadway | Performer | as a member of the Katherine Dunham Troupe; a short-lived production at the Belasco Theatre[56] |

| Carib Song | Broadway | Company | as a member of the Katherine Dunham Troupe; performed at the Adelphi Theatre as an Original Broadway production[56] | |

| 1946 | Bal Nègre | Broadway, and Europe | Performer | as a member of the Katherine Dunham Troupe; widely acclaimed Concert at the Belasco Theatre[56] |

| unknown | Mexico | Performer | performed successfully as a member of the Katherine Dunham Troupe which was under contract with Teatro Americano for more than two months at the request of Doris Duke[56] | |

| 1948 | Caribbean Rhapsody | West End, and Paris | Chorus girl | as a member of the Katherine Dunham Troupe; performed at the Prince of Wales Theatre (West End) and Théâtre des Champs-Élysées (Paris)[57][56] |

| 1949–1950 | unknown | Paris | Herself, Performer |

first solo show / leading performance; performed at Carroll's Niterie; is where Orson Welles discovered her[57][58][59] |

| 1950 | Time Runs | Paris[8] | Helen of Troy | In segment based on Faust; performed "Hungry Little Trouble" written by Duke Ellington; cast by Orson Welles[57] |

| An Evening With Orson Welles | Frankfurt[60] | |||

| 1951 | Dr. Faustus | Paris | with Orson Welles | |

| 1952 | New Faces of 1952 | Broadway | Polynesian girl, Featured dancer, Featured singer |

|

| 1954 | Mrs. Patterson | Broadway | Theodora (Teddy) Hicks | Original Broadway production |

| 1957 | Shinbone Alley | Broadway | Mehitabel | Original Broadway production |

| 1959 | Jolly's Progress | Broadway | Jolly Rivers | |

| 1965 | The Owl and the Pussycat | U.S. National tour | Performer | |

| 1967 | Peg | Regional (US) | ||

| 1970 | The High Bid | London | Performer | |

| 1972 | Bunny | London | Performer | |

| 1974 | Bread and Beans and Things | Aquarius Theater[61] | Performer | |

| 1976 | A Musical Jubilee | U.S. National tour | Performer | |

| 1978 | Timbuktu! | Broadway | Shaleem-La-Lume | Nominated–Tony Award for Best Leading Actress in a Musical |

| 1980 | Cowboy and the Legend | Regional (US) | Performer | |

| 1982 | New Faces of 1952 (Revival) | Off-off-Broadway | Polynesian girl Featured dancer Featured singer |

|

| 1985 | Blues in the Night | U.S. National tour | Performer | |

| 1987 | Follies (London Revival) | London | Carlotta Campion | Replacement for Dolores Gray |

| 1989 | Aladdin | Palace Theatre, Manchester | Slave of the Ring | |

| 1989 | Eartha Kitt in Concert | London | Performer | |

| 1994 | Yes | Edinburgh | Performer | |

| 1995 | Sam's Song | Unitarian Church of All Souls | Performer | Benefit concert |

| 1996 | Lady Day at Emerson's Bar and Grill | Chicago | Billie Holiday | |

| 1998 | The Wizard of Oz (return engagement) | Madison Square Garden, and U.S. National tour | Miss Gulch/The Wicked Witch | |

| 2000 | The Wild Party | Broadway | Delores | Original Broadway production Nominated–Drama Desk Award for Outstanding Featured Actress in a Musical Nominated–Tony Award for Best Featured Actress in a Musical |

| Cinderella | Madison Square Garden, and U.S. National tour | Fairy Godmother | ||

| 2003 | Nine | Broadway | Liliane La Fleur | Replacement for Chita Rivera |

| 2004 | Cinderella (New York City Opera revival) | David H. Koch Theater | Fairy Godmother | |

| 2006 | Mimi le Duck | Off-off-Broadway | Madame Vallet | |

| 2007 | All About Us | Westport Country Playhouse | Performer |

Video games

[edit]| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | The Emperor's New Groove | Yzma | voice role |

Bibliography

[edit]- Thursday's Child (1956)

- Alone with Me: A New Autobiography (1976)

- I'm Still Here: Confessions of a Sex Kitten (1989)

- Rejuvenate!: It's Never Too Late (2001)

Awards and nominations

[edit]- In 1960, the Hollywood Walk of Fame honored her with a star, which can be found on 6656 Hollywood Boulevard.[74][75]

- In 2016, January 17 was announced as Eartha Kitt Day in Kitt's home state of South Carolina. In 2022 the day was enshrined into state law in SC Code § 53-3-75 (2022).[76] South Carolinian Sheldon Rice is credited for beginning the push for legislation declaring her birthday as a state holiday since the time of her death in 2008. State Rep. Gilda Cobb-Hunter first introduced the legislation to create the State holiday in 2011.[76]

References

[edit]- ^ "Obituary: Eartha Kitt"Archived April 19, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. The Guardian. Dec 26 2008. Retrieved April 23, 2024.

- ^ "Eartha Kitt dies at 81; TV’s Catwoman, sultry singer of ‘Santa Baby’" Archived December 28, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. Lon Angeles Times. Dec 26 2008. Retrieved April 23, 2024.

- ^ "Mother Eartha" Archived January 1, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. Philadelphia City Paper. January 17–24, 2002. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ Messer, Kate X. (July 21, 2006). "Just An Old Fashioned Cat". The Austin Chronicle.

- ^ Kitt, Eartha (1990). I'm Still Here. London: Pan. ISBN 0-330-31439-4. OCLC 24719847.

- ^ a b Jack, Adrian (December 17, 2008). "Obituary: Eartha Kitt". The Guardian. Retrieved June 17, 2018.

- ^ a b "Singer-actress Eartha Kitt dies at 81". MSNBC. December 26, 2008. Archived from the original on January 12, 2018. Retrieved May 14, 2013.

- ^ a b c d "Eartha Kitt: Singer who rose from poverty to captivate audiences around the world with her purring voice". The Telegraph. December 26, 2008. Archived from the original on January 11, 2022. Retrieved December 14, 2014.

- ^ a b Sandra Hale Schulman (February 26, 2009). "Eartha Kitt, Chanteuse, Cherokee, and a seducer of audiences, Walked On at 81". Indian Country News. Archived from the original on August 3, 2013.

- ^ Weil, Martin (December 26, 2008). "Bewitching Entertainer Eartha Kitt, 81". The Washington Post. p. B05.

- ^ Williams, John L. (2013). America's Mistress : The Life and Times of Eartha Kitt. London: Quercus. ISBN 978-0-85738-575-8. OCLC 792747512.

- ^ a b Luck, Adam (October 19, 2013). "Eartha Kitt's life was scarred by her failure to learn the identity of her White father, says daughter". The Observer. ISSN 0029-7712. Retrieved April 29, 2023.

- ^ "Singer, Broadway Star Eartha Kitt Dies". Billboard. Associated Press. December 25, 2008. Retrieved September 3, 2019.

- ^ a b c Hoerburger, Rob (December 25, 2008). "Eartha Kitt, a Seducer of Audiences, Dies at 81". The New York Times.

- ^ Hall, Phil (January 4, 2001). "New Faces". Film Threat.

- ^ Wayne, George (June 2001). "Back to Eartha". Vanity Fair. p. 160.

- ^ "Eartha Kitt". Internet Broadway Database. Retrieved May 14, 2013.

- ^ Kitt, Eartha (November 25, 1956). "Thursday's child". New York, Duell, Sloan and Pearce – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Kielty, Martin (November 29, 2020). "Does David Bowie Biopic 'Stardust' Benefit From Being Unofficial?". Ultimate Classic Rock.

- ^ Brown, DeNeen L. (January 19, 2018). "'Sex kitten' vs. Lady Bird: The day Eartha Kitt attacked the Vietnam War at the White House". Washington Post. Retrieved April 10, 2023.

- ^ Buck, Stephanie (March 13, 2017). "The black actress who made Lady Bird Johnson cry; The truth hurts". Medium. Archived from the original on May 31, 2017. Retrieved January 12, 2018.

- ^ Amorosi, A. D. (February 27, 1997). "Eartha Kitt". Philadelphia City Paper. Archived from the original on January 6, 2009.

- ^ James, Frank (December 26, 2008). "Eartha Kitt versus the LBJs". The Swamp. Archived from the original on January 14, 2009.

- ^ Miller, Danny (December 27, 2008). "Ertha Kitt, CIA Target". HuffPost.

- ^ Quarshie, Mabinty. "Eartha Kitt's Vietnam comments nearly ended her career". USA TODAY. Retrieved April 10, 2023.

- ^ Beschloss, Michael. "Eartha Kitt also played "Catwoman" in "Batman" (1966-1968)--met LBJ and later told Lady Bird Johnson at this January 1968 White House lunch". Twitter. Retrieved April 10, 2023.

Eartha Kitt also played "Catwoman" in "Batman" (1966-1968)--met LBJ and later told Lady Bird Johnson at this January 1968 White House lunch, "I have a baby and then you send him off to war. No wonder the kids rebel and take pot"—generating a backlash against her career:

- ^ "When Eartha Kitt Disrupted the Ladies Who Lunch". The New Yorker. February 16, 2022.

- ^ Kerr, Euan (January 27, 2006). "Eartha Kitt is so much more than Catwoman". Minnesota Public Radio. Retrieved April 10, 2023.

interview with Eartha Kitt

- ^ a b c Hersh, Seymour (January 3, 1975). "CIA gave Secret Service a Report containing Gossip about Eartha Kitt after a White House Incident". The New York Times.

- ^ "Eartha Kitt". Britannica.com. Retrieved April 10, 2023.

- ^ Calonico, Scott. "Catwoman vs. The White House". ScottCalonico.com. Retrieved April 10, 2023.

- ^ The New Yorker (February 16, 2022). "When the Government Tried, and Failed, to Silence Catwoman". YouTube. Retrieved April 10, 2023.

- ^ "When Eartha Kitt Spoke Truth to Power at a 1968 White House Luncheon". Open Culture. Retrieved April 10, 2023.

- ^ "Carter Greets Eartha Kitt at White House Where She Shocked Mrs. Johnson in 1968". New York Times. January 30, 1978. Retrieved December 29, 2024.

- ^ Viagas, Robert and Lefkowitz, David. "Mickey Rooney/Eartha Kitt Oz Opens in NY, May 6". Playbill, May 6, 1998

- ^ Jones, Kenneth. The Shoe Fits: R&H's Cinderella Begins Tour Nov. 28 in FL Playbill, November 28, 2000

- ^ Davis, Peter G. (November 22, 2004). "Sweeps Week". New York. Retrieved August 9, 2023.

- ^ Vietnam after the fire / an Acacia Production for Channel Four; produced and directed by J. Edward Milner., Healey Library, University of Massachusetts Boston, retrieved January 4, 2023

- ^ "Where Is My Man". Official Charts Company. Archived from the original on July 11, 2017. Retrieved September 12, 2019.

- ^ Whitburn, Joel (2004). Hot Dance/Disco 1974–2003. Record Research Inc.

- ^ a b Scott Duncan, "George Burns, Eartha Kitt are delightful at 'Lifesongs 1990'", [1] The Baltimore Sun, September 17, 1990.

- ^ "Eartha Kitt to Be Married". The New York Times. May 12, 1960. p. 40. (subscription required)

- ^ Ralis, David (December 26, 2008). "Remembering Eartha Kitt". www.inquirer.com. Retrieved June 18, 2021.

- ^ "Eartha Kitt Wins, Divorce". The New York Times. March 27, 1964.

- ^ "Kitt McDonald is Wed to Charles L. Shapiro". The New York Times. June 14, 1987.

- ^ Johnson, Robert E. (June 14, 1973). "Eartha Kitt Observes Seventh Year With Black Ghetto School". Jet 44: 56.

- ^ Hearings, 90th Cong., 1st Sess. 558 (1967). pp. 559–60.

- ^ Kitt, Eartha (1976). Alone With Me. H. Regnery Co. p. 239. ISBN 9780809283514.

- ^ Blackwell, Joyce (2004). No Peace Without Freedom: Race and the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom. Southern Illinois University Press. ISBN 9780809325641.

- ^ "Eartha Kitt, actress and gay rights ally, dies at age 81". PageOneQ. December 28, 2008. Archived from the original on April 30, 2009.

- ^ Eartha Kitt sings Swedish and talks about her gay-fans on YouTube

- ^ Wilson, Christopher (December 26, 2008). "Seductive singer Eartha Kitt dies at 81". Reuters.

- ^ "Actress Eartha Kitt, 81, Dies at Her Weston Home". Westport Now. December 25, 2008.

- ^ Ms. Lee Brown (October 5, 2013). "Kitt Shapiro (Daughter of Eartha Kitt) Offers Business Advice for Moms & Discusses Mother's Passing & Legacy". Mommynoire.com. Archived from the original on June 22, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Eartha Kitt (visual voices guide)". Behind The Voice Actors. Retrieved November 8, 2024. A green check mark indicates that a role has been confirmed using a screenshot (or collage of screenshots) of a title's list of voice actors and their respective characters found in its credits or other reliable sources of information.

- ^ a b c d e "Selections from the Katherine Dunham Collection". Library of Congress. Retrieved December 14, 2014.

- ^ a b c Anon. (1955). That Bad Eartha 10" Long Play (United Kingdom Version) (sleeve note). Eartha Kitt. His Master's Voice.

- ^ Anon. (1955). Down to Eartha (United Kingdom Version) (sleeve note). Eartha Kitt. His Master's Voice.

- ^ Baker, Rob (October 16, 2014). "Eartha Kitt and Orson Welles in Paris in 1950". Alum Media Ltd. Retrieved December 14, 2014.

- ^ Fanning, Win (August 13, 1950). "Eartha Kitt wins raves in Welles' show at Frankfurt". Stars and Stripes. Retrieved December 14, 2014.

- ^ "Bread and Beans and Things Starring Eartha Kitt at Aquarius". Los Angeles Sentinel. July 11, 1974. p. B-9. ProQuest 565142254.; Sullivan, Dan (July 18, 1974). "Bread and Beans in a New League". Stage Review. Los Angeles Times. p. IV: 1, 15. ProQuest 157629458.

- ^ "29th Annual Annie Awards". Annie Awards. Retrieved April 2, 2023.

- ^ "34th Annual Annie Awards". Annie Awards. Retrieved April 2, 2023.

- ^ "35th Annual Annie Awards". Annie Awards. Retrieved April 2, 2023.

- ^ "Black Reel Awards – Past Nominees & Winners by Category". Black Reel Awards. Retrieved April 2, 2023.

- ^ "Nominations Announced for the Emmy Award for Excellence in Morning Programming". National Academy of Television Arts and Sciences. March 26, 2007. Archived from the original on September 27, 2016. Retrieved June 16, 2007.

- ^ "The National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences announces 35th Annual Daytime Entertainment Emmy Award nominations". National Academy of Television Arts and Sciences. April 30, 2008. Archived from the original on February 3, 2017. Retrieved August 24, 2017.

- ^ "The National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences announces the 37th Annual Daytime Entertainment Emmy Award nominations" (PDF). National Academy of Television Arts and Sciences. May 12, 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 4, 2016. Retrieved August 24, 2017.

- ^ "Nominees and Recipients – 2000 Awards". Drama Desk Awards. Retrieved April 2, 2023.

- ^ "Eartha Kitt". Grammy Awards. Retrieved April 2, 2023.

- ^ "Eartha Kitt". Academy of Television Arts & Sciences. Retrieved April 2, 2023.

- ^ "1978 Tony Awards". Tony Awards. Retrieved April 2, 2023.

- ^ "2000 Tony Awards". Tony Awards. Retrieved April 2, 2023.

- ^ "Eartha Kitt". Hollywood Walk of Fame. October 25, 2019. Retrieved April 2, 2023.

- ^ "Eartha Kitt tickets competition". The Telegraph. January 24, 2008. Archived from the original on January 11, 2022.

- ^ a b "2022 South Carolina Code of Laws :: Title 53 - Sundays, Holidays and Other Special Days :: Chapter 3 - Special Days :: Section 53-3-75. Eartha Kitt Day". Justia Law. Retrieved January 21, 2024.

Further reading

[edit]- Gent, Helen (May 4, 2009). "Eartha Kitt: The Feline Femme Fatale". Marie Claire (Australia).

- Kitt, Eartha (1976). Alone with Me : A New Autobiography. Chicago: H. Regnery. ISBN 0-8092-8351-4. OCLC 1945260.

- Walsh, David (December 27, 2008). "Harold Pinter and Eartha Kitt, artists and opponents of imperialist war". World Socialist Web Site.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Eartha Kitt at IMDb

- Eartha Kitt at the TCM Movie Database

- Eartha Kitt at the Internet Broadway Database

- Eartha Kitt at the Internet Off-Broadway Database

- Eartha Kitt at The Interviews: An Oral History of Television

- Eartha Kitt at TV Guide

- Image of Eartha Kitt with her fiance Bill McDonald recovering stolen items at a pawnshop in Los Angeles, California, 1960. Los Angeles Times Photographic Archive (Collection 1429). UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles.

- 1927 births

- 2008 deaths

- 20th-century African-American women singers

- 20th-century African-American actresses

- 20th-century American actresses

- 20th-century American singers

- 20th-century American women singers

- 21st-century African-American women singers

- 21st-century African-American actresses

- 21st-century American actresses

- 21st-century American singers

- 21st-century American women singers

- Activists from New York (state)

- Actresses from Manhattan

- Actresses from South Carolina

- African-American activists

- African-American female comedians

- African-American comedians

- African-American jazz musicians

- American anti–Vietnam War activists

- American film actresses

- American jazz singers

- American LGBTQ rights activists

- American musical theatre actresses

- American stage actresses

- American television actresses

- American video game actresses

- American voice actresses

- American women comedians

- Annie Award winners

- American cabaret singers

- Comedians from Manhattan

- Comedians from South Carolina

- Deaths from cancer in Connecticut

- Deaths from colorectal cancer in the United States

- French-language singers of the United States

- Jazz musicians from Connecticut

- Jazz musicians from New York (state)

- Musicians from Manhattan

- People from Harlem

- People from New Milford, Connecticut

- People from North, South Carolina

- People from Pound Ridge, New York

- People from Weston, Connecticut

- RCA Victor artists

- Singers from South Carolina

- American women civil rights activists