Moon landing conspiracy theories

Moon landing conspiracy theories claim that some or all elements of the Apollo program and the associated Moon landings were hoaxes staged by NASA, possibly with the aid of other organizations. The most notable claim of these conspiracy theories is that the six crewed landings (1969–1972) were faked and that twelve Apollo astronauts did not actually land on the Moon. Various groups and individuals have made claims since the mid-1970s that NASA and others knowingly misled the public into believing the landings happened, by manufacturing, tampering with, or destroying evidence including photos, telemetry tapes, radio and TV transmissions, and Moon rock samples.

Much third-party evidence for the landings exists, and detailed rebuttals to the hoax claims have been made.[1] Since the late 2000s, high-definition photos taken by the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) of the Apollo landing sites have captured the Lunar Module descent stages and the tracks left by the astronauts.[2][3] In 2012, images were released showing five of the six Apollo missions' American flags erected on the Moon still standing. The exception is that of Apollo 11, which has lain on the lunar surface since being blown over by the Lunar Module Ascent Propulsion System.[4][5]

Reputable experts in science and astronomy regard the claims as pseudoscience and demonstrably false.[6][7] Opinion polls taken in various locations between 1994 and 2009 have shown that between 6% and 20% of Americans, 25% of Britons, and 28% of Russians surveyed believe that the crewed landings were faked. Even as late as 2001, the Fox television network documentary Conspiracy Theory: Did We Land on the Moon? claimed NASA faked the first landing in 1969 to win the Space Race.[8]

Origins

An early and influential book about the subject of a Moon-landing conspiracy, We Never Went to the Moon: America's Thirty Billion Dollar Swindle, was self-published in 1976 by Bill Kaysing, a former US Navy officer with a Bachelor of Arts in English.[9] Despite having no knowledge of rockets or technical writing,[10] Kaysing was hired as a senior technical writer in 1956 by Rocketdyne, the company that built the F-1 engines used on the Saturn V rocket.[11][12] He served as head of the technical publications unit at the company's Propulsion Field Laboratory until 1963. The many allegations in Kaysing's book effectively began discussion of the Moon landings being faked.[13][14] The book claims that the chance of a successful crewed landing on the Moon was calculated to be 0.0017%, and that despite close monitoring by the USSR, it would have been easier for NASA to fake the Moon landings than to really go there.[15][16]

In 1980, the Flat Earth Society accused NASA of faking the landings, arguing that they were staged by Hollywood with Walt Disney sponsorship, based on a script by Arthur C. Clarke and directed by Stanley Kubrick.[a][17] Folklorist Linda Dégh suggests that writer-director Peter Hyams' film Capricorn One (1978), which shows a hoaxed journey to Mars in a spacecraft that looks identical to the Apollo craft, might have given a boost to the hoax theory's popularity in the post-Vietnam War era. Dégh sees a parallel with other attitudes during the post-Watergate era, when the American public were inclined to distrust official accounts. Dégh writes: "The mass media catapult these half-truths into a kind of twilight zone where people can make their guesses sound as truths. Mass media have a terrible impact on people who lack guidance."[18] In A Man on the Moon,[19] first published in 1994, Andrew Chaikin mentions that at the time of Apollo 8's lunar-orbit mission in December 1968,[20] similar conspiracy ideas were already in circulation.[21]

Claimed motives of the United States and NASA

Those who believe the Moon landings were faked offer several theories about the motives of NASA and the United States government. The three main theories are below.

Space Race

Motivation for the United States to engage the Soviet Union in a Space Race can be traced to the Cold War. Landing on the Moon was viewed as a national and technological accomplishment that would generate world-wide acclaim. But going to the Moon would be risky and expensive, as exemplified by President John F. Kennedy famously stating in a 1962 speech that the United States chose to go because it was hard.[22]

Hoax theory debunker Phil Plait says in his 2002 book Bad Astronomy[b] that the Soviets – with their own competing Moon program, an extensive intelligence network and a formidable scientific community able to analyze NASA data – would have "cried foul" if the United States tried to fake a Moon landing,[23] especially since their own program had failed. Proving a hoax would have been a huge propaganda win for the Soviets. Instead, far from calling the landings a hoax, the third edition (1970–1979) of the Great Soviet Encyclopedia (which was translated into English between 1974 and 1983 by Macmillan Publishers, and was later made available online by TheFreeDictionary.com[24]) contained many articles reporting the landings as factual, such as its article on Neil Armstrong.[25] Indeed their article on space exploration describes the Apollo 11 landing as "the third historic event" of the space age, following the launch of Sputnik in 1957, and Yuri Gagarin's flight in 1961.[26]

Conspiracist Bart Sibrel responded, incorrectly asserting that, "the Soviets did not have the capability to track deep space craft until late in 1972, immediately after which, the last three Apollo missions were abruptly canceled."[27] Those missions were canceled, not abruptly, but for cost-cutting reasons. The announcements were made in January and September 1970,[28] two full years before the "late 1972" claimed by Sibrel.[29] (See Vietnam War below.)

In fact, the Soviets had been sending uncrewed spacecraft to the Moon since 1959,[30] and "during 1962, deep space tracking facilities were introduced at IP-15 in Ussuriisk and IP-16 in Evpatoria (Crimean Peninsula), while Saturn communication stations were added to IP-3, 4 and 14,"[31] the last of which having a 100 million km (62 million mi) range.[32] The Soviet Union tracked the Apollo missions at the Space Transmissions Corps, which was "fully equipped with the latest intelligence-gathering and surveillance equipment."[33] Vasily Mishin, in an interview for the article "The Moon Programme That Faltered," describes how the Soviet Moon program dwindled after the Apollo landings.[34]

In May 2023 Dmitry Rogozin, former director general of the Russian space agency Roscosmos, expressed doubt that U.S. astronauts landed on the Moon. He complained of not receiving a satisfactory answer when he asked his agency to provide evidence. He said his colleagues at Roscosmos were angry about his questions and did not want to undermine cooperation with NASA.[35]

NASA funding and prestige

Conspiracy theorists claim that NASA faked the landings to avoid humiliation and to ensure that it continued to get funding. NASA raised "about US$30 billion" to go to the Moon, and Kaysing claimed in his book that this could have been used to "pay off" many people.[36] Since most conspiracists believe that sending men to the Moon was impossible at the time,[37] they argue that landings had to be faked to fulfill Kennedy's 1961 goal, "before this decade is out, of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to the Earth."[38] In fact, NASA accounted for the cost of Apollo to the US Congress in 1973, totaling US$25.4 billion.[39]

Mary Bennett and David Percy claimed in the 2001 book Dark Moon: Apollo and the Whistle-Blowers, that, with all the known and unknown hazards,[40] NASA would not risk broadcasting an astronaut getting sick or dying on live television.[41] The counter-argument generally given is that NASA in fact did incur a great deal of public humiliation and potential political opposition to the program by losing an entire crew in the Apollo 1 fire during a ground test, leading to its upper management team being questioned by Senate and House of Representatives space oversight committees.[42] There was in fact no video broadcast during either the landing or takeoff because of technological limitations.[43]

Vietnam War

The American Patriot Friends Network claimed in 2009 that the landings helped the United States government distract public attention from the unpopular Vietnam War, and so crewed landings suddenly ended about the same time that the United States ended its involvement in the war.[44] In fact, the ending of the landings was not "sudden" (see Space Race above). The war was one of several federal budget items with which NASA had to compete; NASA's budget peaked in 1966, and fell by 42% by 1972.[45] This was the reason the final flights were cut, along with plans for even more ambitious follow-on programs such as a permanent space station and crewed flight to Mars.[46]

Hoax claims and rebuttals

Many Moon-landing conspiracy theories have been proposed, alleging that the landings either did not occur and NASA staff lied, or that the landings did occur but not in the way that has been reported. Conspiracists have focused on perceived gaps or inconsistencies in the historical record of the missions. The foremost idea is that the whole crewed landing program was a hoax from start to end. Some claim that the technology did not exist to send men to the Moon or that the Van Allen radiation belts, solar flares, solar wind, coronal mass ejections, and cosmic rays made such a trip impossible.[13]

Scientists Vince Calder and Andrew Johnson have given detailed answers to conspiracists' claims on the Argonne National Laboratory website.[47] They show that NASA's portrayal of the Moon landing is fundamentally accurate, allowing for such common mistakes as mislabeled photos and imperfect personal recollections. Using the scientific process, any hypothesis may be rejected if it is contradicted by the observable facts. The "real landing" hypothesis is a single story since it comes from a single source, but there is no unity in the hoax hypothesis because hoax accounts vary between conspiracists.[48]

Number of conspirators involved

According to James Longuski, the conspiracy theories are impossible because of their size and complexity. The conspiracy would have to involve more than 400,000 people who worked on the Apollo project for nearly ten years, the twelve men who walked on the Moon, the six others who flew with them as command module pilots, and another six astronauts who orbited the Moon.[c] Hundreds of thousands of people would have had to keep the secret, including astronauts, scientists, engineers, technicians, and skilled laborers. Longuski argues that it would have been much easier to really land on the Moon than to generate such a huge conspiracy to fake the landings.[49][50] To date, nobody from the United States government or NASA linked to the Apollo program has said that the Moon landings were hoaxes. Penn Jillette made note of this in the "Conspiracy Theories" episode of his television show Penn & Teller: Bullshit! in 2005.[51] Physicist David Robert Grimes estimated the time that it would take for a conspiracy to be exposed based on the number of people involved.[52][53] His calculations used data from the PRISM surveillance program, the Tuskegee syphilis experiment, and the FBI forensic scandal. Grimes estimated that a Moon landing hoax would require the involvement of 411,000 people and would be exposed within 3.68 years. His study did not consider exposure by sources outside of the alleged conspiracy; it only considered exposure from within through whistleblowers or incompetence.[54]

Photographic and film oddities

Moon-landing conspiracists focus heavily on NASA photos, pointing to oddities in photos and films taken on the Moon. Photography experts (including those unrelated to NASA) have replied that the oddities are consistent with what should be expected from a real Moon landing, and are not consistent with manipulated or studio imagery. Some main arguments (set in plain text) and counter-arguments (set in italics) are listed below.

1. In some photos, the crosshairs appear to be behind objects. The cameras were fitted with a Réseau plate (a clear glass plate with a reticle etched on), making it impossible for any photographed object to appear in front of the grid. Conspiracists often use this evidence to suggest that objects were "pasted" over the photographs, and hence obscure the reticle.

- This effect only appears in copied and scanned photos, not any originals. It is caused by overexposure: the bright white areas of the emulsion "bleed" over the thin black crosshairs. The crosshairs are only about 0.004 inches thick (0.1 mm) and emulsion would only have to bleed about half that much to fully obscure it. Furthermore, there are many photos where the middle of the crosshair is "washed-out" but the rest is intact. In some photos of the American flag, parts of one crosshair appear on the red stripes, but parts of the same crosshair are faded or invisible on the white stripes. There would have been no reason to "paste" white stripes onto the flag.[55]

-

Enlargement of a poor-quality 1998 scan; both the crosshair and part of the red stripe have "bled out"

-

Enlargement of a higher-quality 2004 scan, crosshair and red stripe visible

-

David Scott salutes the American flag during the Apollo 15 mission. The arms of the crosshair are washed-out on the white stripes of the flag (Photo ID: AS15-88-11863).

-

Close-up of the flag, showing washed-out crosshairs

2. Crosshairs are sometimes rotated or in the wrong place.

- This is a result of popular photos being cropped or rotated for aesthetic impact.[55]

3. The quality of the photographs is implausibly high.

- There are many poor quality photos taken by the Apollo astronauts. NASA chose to publish only the best examples.[55][56]

- The Apollo astronauts used high-resolution Hasselblad 500 EL cameras with Carl Zeiss optics and a 70 mm medium format film magazine.[57][58]

4. There are no stars in any of the photos; the Apollo 11 astronauts also stated in post-mission press conferences that they did not remember seeing any stars during extravehicular activity (EVA).[59] Conspiracists contend that NASA chose not to put the stars into the photos because astronomers would have been able to use them to determine whether the photos were taken from the Earth or the Moon, by means of identifying them and comparing their celestial position and parallax to what would be expected for either observation site.

- The astronauts were talking about naked-eye sightings of stars during the lunar daytime. They regularly sighted stars through the spacecraft navigation optics while aligning their inertial reference platforms, the Apollo PGNCS.[60]

- Stars are rarely seen in Space Shuttle, Mir, Earth observation photos, or even photos taken at sporting events held at night. The light from the Sun in outer space in the Earth-Moon system is at least as bright as the sunlight that reaches the Earth's surface on a clear day at noon, so cameras used for imaging subjects illuminated by sunlight are set for a daylight exposure. The dim light of the stars simply does not provide enough exposure to record visible images. All crewed landings happened during the lunar daytime. Thus, the stars were outshone by the Sun and by sunlight reflected off the Moon's surface. The astronauts' eyes were adapted to the sunlit landscape around them so that they could not see the relatively faint stars.[61][62] The astronauts could see stars with the naked eye only when they were in the shadow of the Moon.[63][64]

- Camera settings can turn a well-lit background to black when the foreground object is brightly lit, forcing the camera to increase shutter speed so that the foreground light does not wash out the image. A demonstration of this effect is here.[65] The effect is similar to not being able to see stars from a brightly lit parking lot at night; the stars only become visible when the lights are turned off.

- The Far Ultraviolet Camera was taken to the lunar surface on Apollo 16 and operated in the shadow of the Apollo Lunar Module (LM). It took photos of Earth and of many stars, some of which are dim in visible light but bright in the ultraviolet. These observations were later matched with observations taken by orbiting ultraviolet telescopes. Furthermore, the positions of those stars with respect to Earth are correct for the time and location of the Apollo 16 photos.[66][67]

- Photos of the planet Venus were taken from the Moon's surface by astronaut Alan Shepard during the Apollo 14 mission.[69]

-

Short-exposure photo of the International Space Station (ISS) taken from Space Shuttle Atlantis in February 2008 during STS-122 – one of many photos taken in space where no stars are visible

-

Earth and Mir in June 1995, an example of how sunlight can outshine the stars, making them invisible

-

Long-exposure photo taken from the Moon's surface by Apollo 16 astronauts using the Far Ultraviolet Camera. It shows the Earth with the correct background of stars.

-

Long-exposure photo (1.6 seconds at f-2.8, ISO 10000) from the ISS in July 2011 of Space Shuttle Atlantis re-entry in which some stars are visible. In this image, the Earth is lit by moonlight, not sunlight.

5. The angle and color of shadows are inconsistent. This suggests that artificial lights were used.

- Shadows on the Moon are complicated by reflected light, uneven ground, wide-angle lens distortion, and lunar dust. There are several light sources: the Sun, sunlight reflected from the Earth, sunlight reflected from the Moon's surface, and sunlight reflected from the astronauts and the Lunar Module. Light from these sources is scattered by lunar dust in many directions, including into shadows. Shadows falling into craters and hills may appear longer, shorter, and distorted.[70] Furthermore, shadows display the properties of vanishing point perspective, leading them to converge to a point on the horizon.

- This theory was further debunked on the MythBusters episode "NASA Moon Landing".

6. There are identical backgrounds in photos which were allegedly taken miles apart. This suggests that a painted background was used.

- Backgrounds were not identical, just similar. What appear as nearby hills in some photos are actually mountains many miles away. On Earth, objects that are farther away will appear fainter and less detailed. On the Moon, there is no atmosphere or haze to obscure far-away objects, thus they appear clearer and nearer.[71] Furthermore, there are very few objects such as trees to help judge distance. One such case is debunked in "Who Mourns For Apollo?" by Mike Bara.[72]

7. The number of photos taken is implausibly high—up to one photo per 50 seconds.[73]

- Simplified gear with fixed settings allowed two photos a second. Many were taken immediately after each other as stereo pairs or panorama sequences. The calculation (one per 50 seconds) was based on a lone astronaut on the surface, and does not take into account that there were two astronauts sharing the workload and simultaneously taking photographs during an Extra-vehicular activity (EVA).

8. The photos contain artifacts like the two seemingly matching "C"s on a rock and on the ground. These may be labeled studio props.

9. A woman named Una Ronald (a pseudonym created by the authors of the source[75]) from Perth, Australia, said that she saw a Coca-Cola bottle roll across the lower right quadrant of her television screen that was displaying the live broadcast of the Apollo 11 EVA. She also said that several letters appeared in The West Australian discussing the Coca-Cola bottle incident within ten days of the lunar landing.[76]

- No such newspaper reports or recordings have been found.[77] Ronald's claims have only been relayed by one source.[78] There are also flaws in the story, such as the statement that she had to stay up late to watch the Moon landing live, which is easily discounted by many witnesses in Australia who watched the landing in the middle of the daytime.[79][80]

10. The 1994 book Moon Shot[81] contains an obviously fake composite photo of Alan Shepard hitting a golf ball on the Moon with another astronaut.

- It was used instead of the only existing real images from the TV monitor, which the editors seemingly felt were too grainy for their book. The book publishers did not work for NASA, although the authors were retired NASA astronauts.

11. There appear to be "hot spots" in some photos which look as though a large spotlight was used in place of the Sun.

- Pits on the Moon's surface focus and reflect light like the tiny glass spheres used in the coating of street signs, or dewdrops on wet grass. This creates a glow around the photographer's own shadow when it appears in a photograph (see Heiligenschein).

- If the astronaut is standing in sunlight while photographing into shade, light reflected off his white spacesuit yields a similar effect to a spotlight.[82]

- Some widely published Apollo photos were high-contrast copies. Scans of the original transparencies are generally much more evenly lit. An example is shown below:

-

Original photo of Buzz Aldrin during Apollo 11

-

The more famous edited version. The contrast has been increased, yielding the "spotlight effect", and a black band has been pasted at the top.

12. Who filmed Neil Armstrong stepping onto the Moon?

- Cameras on the Lunar Module did. The Apollo TV camera mounted in the Modularized Equipment Stowage Assembly (MESA) of the Apollo Lunar Module gave a view from the exterior. While still on the Module's ladder steps, Armstrong deployed the MESA from the side of the Lunar Module, unpacking the TV camera. The camera was then powered on and a signal transmitted back to Earth. This meant that upwards of 600 million people on Earth could watch the live feed with only a very slight delay. Similar technology was also used on subsequent Apollo missions.[83][84][85][86] It was also filmed from an automatic 16mm movie camera mounted in a window of the Lunar Module.

Environment

1. The astronauts could not have survived the trip because of exposure to radiation from the Van Allen radiation belt and galactic ambient radiation (see radiation poisoning and health threat from cosmic rays). Some conspiracists have suggested that Starfish Prime (a high-altitude nuclear test in 1962) formed another intense layer on the Van Allen belt.[87]

- There are two main Van Allen belts – the inner belt and the outer belt – and a transient third belt.[88] The inner belt is the more dangerous one, containing energetic protons. The outer one has less-dangerous low-energy electrons (Beta particles).[89][90] The Apollo spacecraft passed through the inner belt in a matter of minutes and the outer belt in about 1+1⁄2 hours.[90] The astronauts were shielded from the ionizing radiation by the aluminum hulls of the spacecraft.[90][91] Furthermore, the orbital transfer trajectory from Earth to the Moon through the belts was chosen to lessen radiation exposure.[91] Even James Van Allen, the discoverer of the Van Allen belt, rebutted the claims that radiation levels were too harmful for the Apollo missions.[87] Phil Plait cited an average dose of less than 1 rem (10 mSv), which is equivalent to the ambient radiation received by living at sea level for three years.[92] The total radiation received on the trip was about the same as allowed for workers in the nuclear energy field for a year[90][93] and not much more than what Space Shuttle astronauts received.[89]

2. Film in the cameras would have been fogged by this radiation.

- The film was kept in metal containers that stopped radiation from fogging the emulsion.[94] Furthermore, film was not fogged in lunar probes such as the Lunar Orbiter and Luna 3 (which used on-board film development processes).

3. The Moon's surface during the daytime is so hot that camera film would have melted.

- There is no atmosphere to efficiently bind lunar surface heat to devices that are not in direct contact with it. In a vacuum, only radiation remains as a heat transfer mechanism. The physics of radiative heat transfer are thoroughly understood, and the proper use of passive optical coatings and paints was enough to control the temperature of the film within the cameras; Lunar Module temperatures were controlled with similar coatings that gave them a gold color. The Moon's surface does get very hot at lunar noon, but every Apollo landing was made shortly after lunar sunrise at the landing site; the Moon's day is about 29+1⁄2 Earth days long, meaning that one Moon day (dawn to dusk) lasts nearly fifteen Earth days. During the longer stays, the astronauts did notice increased cooling loads on their spacesuits as the sun and surface temperature continued to rise, but the effect was easily countered by the passive and active cooling systems.[95] The film was not in direct sunlight, so it was not overheated.[96]

4. The Apollo 16 crew could not have survived a big solar flare firing out when they were on their way to the Moon.

5. The flag placed on the surface by the astronauts fluttered despite there being no wind on the Moon. This suggests that it was filmed on Earth and a breeze caused it to flutter. Sibrel said that it may have been caused by indoor fans used to cool the astronauts, since their spacesuit cooling systems would have been too heavy on Earth.

- The flag was fastened to an Г-shaped rod (see Lunar Flag Assembly) so that it did not hang down. It only seemed to flutter when the astronauts were moving it into position. Without air drag, these movements caused the free corner of the flag to swing like a pendulum for some time. It was rippled because it had been folded during storage, and the ripples could be mistaken for movement in a still photo. Videos show that, when the astronauts let go of the flagpole, it vibrates briefly but then remains still.[99][100][101]

- This theory was further debunked on the MythBusters episode "NASA Moon Landing".

-

Cropped photo of Buzz Aldrin saluting the flag. The fingers of Aldrin's right hand can be seen behind his helmet.

-

Cropped photo taken a few seconds later. Buzz Aldrin's hand is down, head turned toward the camera; the flag is unchanged.

-

Animation of the two photos, showing that Armstrong's camera moved between exposures, but the flag is not waving.

6. Footprints in the Moondust are unexpectedly well preserved, despite the lack of moisture.

- Moondust has not been weathered like the sand on Earth, and it has sharp edges. This allows the dust particles to stick together and hold their shape in the vacuum. The astronauts likened it to "talcum powder or wet sand".[72]

- This theory was further debunked on the MythBusters episode "NASA Moon Landing".

7. The alleged Moon landings used either a sound stage or were filmed outside in a remote desert with the astronauts either using harnesses or slow-motion photography to make it look like they were on the Moon.

- The HBO miniseries "From the Earth to the Moon" used the sound-stage and harness setup, as did a scene from the movie "Apollo 13". It is clearly seen from those films that, when dust rose, it did not quickly settle; some dust briefly formed clouds. In the film footage from the Apollo missions, dust kicked up by the astronauts' boots and the wheels of the Lunar Roving Vehicles rose quite high due to the lower lunar gravity, and it settled quickly to the ground in an uninterrupted parabolic arc since there was no air to suspend it. Even if there had been a sound stage for hoax Moon landings that had the air pumped out, the dust would have reached nowhere near the height and trajectory as in the Apollo film footage because of Earth's greater gravity.

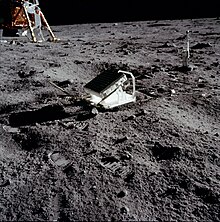

- During the Apollo 15 mission, David Scott did an experiment by dropping a hammer and a falcon feather at the same time. Both fell at the same rate and hit the ground at the same time. This proved that he was in a vacuum.[102]

- If the landings were filmed outside in a desert, heat waves would be present on the surface in mission videos, but no such heat waves exist in the footage. If the landings were filmed in a sound stage, several anomalies would occur, including a lack of parallax, and an increase or decrease in the size of the backdrop if the camera moved. Footage was filmed while the rover was in motion, and yet no evidence is present of any change in the size of the background.

- This theory was further debunked on the MythBusters episode "NASA Moon Landing".

-

David Scott drops a hammer and feather on the Moon.

Mechanical issues

1. The Lunar Modules made no blast craters or any sign of dust scatter.[103]

- No crater should be expected. The 10,000 lb (4,500 kg) thrust Descent Propulsion System was throttled down very far during the final landing.[104] The Lunar Module was no longer quickly decelerating, so the descent engine only had to support the lander's own weight, which was lessened by the Moon's gravity and by the near exhaustion of the descent propellants. At landing, the engine thrust divided by the nozzle exit area is only about 1.5 psi (10 kPa).[105][106]

- Beyond the engine nozzle, the plume spreads, and the pressure drops very quickly. Rocket exhaust gasses expand much more quickly after leaving the engine nozzle in a vacuum than in an atmosphere. The effect of an atmosphere on rocket plumes can be easily seen in launches from Earth; as the rocket rises through the thinning atmosphere, the exhaust plumes broaden very noticeably. To lessen this, rocket engines made for vacuums have longer bells than those made for use on Earth, but they still cannot stop this spreading. The lander's exhaust gases, therefore, expanded quickly well beyond the landing site. The descent engines did scatter a lot of very fine surface dust as seen in 16mm movies of each landing, and many mission commanders spoke of its effect on visibility. The landers were generally moving horizontally as well as vertically, and photos do show scouring of the surface along the final descent path. Finally, the lunar regolith is very compact below its surface dust layer, making it impossible for the descent engine to blast out a crater.[107] A blast crater was measured under the Apollo 11 lander using shadow lengths of the descent engine bell and estimates of the amount that the landing gear had compressed and how deep the lander footpads had pressed into the lunar surface, and it was found that the engine had eroded between 100 and 150 mm (4 and 6 in) of regolith out from underneath the engine bell during the final descent and landing.[108]

2. The second stage of the launch rocket or the Lunar Module ascent stage or both made no visible flame.

- The Lunar Modules used Aerozine 50 (fuel) and dinitrogen tetroxide (oxidizer) propellants, chosen for simplicity and reliability; they ignite hypergolically (upon contact) without the need for a spark. These propellants produce a nearly transparent exhaust.[109] The same fuel was used by the core of the American Titan II rocket. The transparency of their plumes is apparent in many launch photos. The plumes of rocket engines fired in a vacuum spread out very quickly as they leave the engine nozzle (see above), further lessening their visibility. Finally, rocket engines often run "rich" to slow internal corrosion. On Earth, the excess fuel burns in contact with atmospheric oxygen, enhancing the visible flame. This cannot happen in a vacuum.

-

Apollo 17 LM leaving the Moon; rocket exhaust visible only briefly

-

Apollo 8 launch through the first stage separation

-

Exhaust flame may not be visible outside the atmosphere, as in this photo. Rocket engines are the dark structures at the bottom center.

-

The launch of a Titan II, burning hypergolic Aerozine-50/N2O4, 1.9 MN (430,000 lbf) of thrust. Note the near-transparency of the exhaust, even in air (water is being sprayed up from below).

-

Bright flame from first stage of the Saturn V, burning RP-1

3. The Lunar Modules weighed 17 tons and made no mark on the Moondust, yet footprints can be seen beside them.[110]

- On the surface of the Earth, Apollo 11's fueled and crewed Lunar Module Eagle would have weighed approximately 17 short tons (15,000 kg). On the surface of the Moon, however, after expending fuel and oxidizer on its descent from lunar orbit, the lander weighed about 1,200 kg (2,700 pounds).[111] The astronauts were much lighter than the lander, but their boots were much smaller than the lander's approximately 91 cm (3 ft) diameter footpads.[112] Pressure (or force per unit area) rather than mass determines the amount of regolith compression. In some photos, the footpads did press into the regolith, especially when they moved sideways at touchdown. (The bearing pressure under Apollo 11's footpads, with the lander being about 44 times the weight of an EVA-configured astronaut, would have been of similar magnitude to the bearing pressure exerted by the astronauts' boots.)[113]

4. The air conditioning units that were part of the astronauts' spacesuits could not have worked in an environment of no atmosphere.[114]

- The cooling units could only work in a vacuum. Water from a tank in the backpack flowed out through tiny pores in a metal sublimator plate where it quickly vaporized into space. The loss of the heat of vaporization froze the remaining water, forming a layer of ice on the outside of the plate that also sublimated into space (turning from a solid directly into a gas). A separate water loop flowed through the LCG (Liquid Cooling Garment) worn by the astronaut, carrying his metabolic waste heat through the sublimator plate where it was cooled and returned to the LCG. The 5.4 kg (12 lb) of feedwater gave about eight hours of cooling; because of its bulk, it was often the limiting consumable on the length of an EVA.

Transmissions

1. There should have been more than a two-second delay in communications between Earth and the Moon, at a distance of 250,000 mi (400,000 km).

- The round-trip light travel time of more than two seconds is apparent in all the real-time recordings of the lunar audio, but this does not always appear as expected. There may also be some documentary films where the delay has been edited out. Reasons for editing the audio may be time constraints or in the interest of clarity.[115]

2. Typical delays in communication were about 0.5 seconds.

- Claims that the delays were only half a second are untrue, as examination of the original recordings shows. Also, there should not be a consistent time delay between every response, as the conversation is being recorded at one end by Mission Control. Responses from Mission Control could be heard without any delay, as the recording is being made at the same time that Houston receives the transmission from the Moon.

3. The Parkes Observatory in Australia was billed to the world for weeks as the site that would be relaying communications from the first moonwalk. However, five hours before transmission they were told to stand down.

- The timing of the first moonwalk was changed after the landing. In fact, delays in getting the moonwalk started meant that Parkes did cover almost the entire Apollo 11 moonwalk.[116]

4. Parkes supposedly had the clearest video feed from the Moon, but Australian media and all other known sources ran a live feed from the United States.

- That was the original plan and the official policy, but the Australian Broadcasting Commission (ABC) did take the transmission direct from the Parkes and Honeysuckle Creek radio telescopes. These were converted to NTSC television at Paddington in Sydney. This meant that Australian viewers saw the moonwalk several seconds before the rest of the world.[117] See also Parkes radio astronomer John Sarkissian's article "On Eagle's Wings: The Parkes Observatory's Support of the Apollo 11 Mission".[118] The events surrounding the Parkes Observatory's role in relaying the live television of the moonwalk were portrayed in a slightly fictionalized Australian film comedy "The Dish" (2000).

5. Better signal was supposedly received at Parkes Observatory when the Moon was on the opposite side of the planet.

- This is not supported by the detailed evidence and logs from the missions.[119]

Missing data

Blueprints and design and development drawings of the machines involved are missing.[120][121] Apollo 11 data tapes are also missing, containing telemetry and the high-quality video (before scan conversion from slow-scan TV to standard TV) of the first moonwalk.[122][123]

Tapes

Dr. David R. Williams (NASA archivist at Goddard Space Flight Center) and Apollo 11 flight director Eugene F. Kranz both acknowledged that the original high-quality Apollo 11 telemetry data tapes are missing. Conspiracists see this as evidence that they never existed.[122] The Apollo 11 telemetry tapes were different from the telemetry tapes of the other Moon landings because they contained the raw television broadcast. For technical reasons, the Apollo 11 lander carried a slow-scan television (SSTV) camera (see Apollo TV camera). To broadcast the pictures to regular television, a scan conversion had to be done. The radio telescope at Parkes Observatory in Australia was able to receive the telemetry from the Moon at the time of the Apollo 11 moonwalk.[118] Parkes had a bigger antenna than NASA's antenna in Australia at the Honeysuckle Creek Tracking Station, so it received a better picture. It also received a better picture than NASA's antenna at Goldstone Deep Space Communications Complex. This direct TV signal, along with telemetry data, was recorded onto one-inch fourteen-track analog tape at Parkes. The original SSTV transmission had better detail and contrast than the scan-converted pictures, and it is this original tape that is missing.[124] A crude, real-time scan conversion of the SSTV signal was done in Australia before it was broadcast worldwide. However, still photos of the original SSTV image are available (see photos). About fifteen minutes of it were filmed by an amateur 8 mm film camera and these are also available. Later Apollo missions did not use SSTV. At least some of the telemetry tapes still exist from the ALSEP scientific experiments left on the Moon (which ran until 1977), according to Dr. Williams. Copies of those tapes have been found.[125]

Others are looking for the missing telemetry tapes for different reasons. The tapes contain the original and highest quality video feed from the Apollo 11 landing. Some former Apollo personnel want to find the tapes for posterity, while NASA engineers looking towards future Moon missions believe that the tapes may be useful for their design studies. They have found that the Apollo 11 tapes were sent for storage at the U.S. National Archives in 1970, but by 1984, all the Apollo 11 tapes had been returned to the Goddard Space Flight Center at their request. The tapes are believed to have been stored rather than re-used.[126] Goddard was storing 35,000 new tapes per year in 1967,[127] even before the Moon landings.

In November 2006, COSMOS Online reported that about 100 data tapes recorded in Australia during the Apollo 11 mission had been found in a small marine science laboratory in the main physics building at the Curtin University of Technology in Perth, Australia. One of the old tapes has been sent to NASA for analysis. The slow-scan television images were not on the tape.[125]

In July 2009, NASA indicated that it must have erased the original Apollo 11 Moon footage years ago so that it could re-use the tape. In December 2009, NASA issued a final report on the Apollo 11 telemetry tapes.[128] Senior engineer Dick Nafzger was in charge of the live TV recordings during the Apollo missions, and he was put in charge of the restoration project. After a three-year search, the "inescapable conclusion" was that about 45 tapes (estimated 15 tapes recorded at each of the three tracking stations) of Apollo 11 video were erased and re-used, said Nafzger.[129] Lowry Digital had been tasked with restoring the surviving footage in time for the 40th anniversary of the Apollo 11 landing. Lowry Digital president Mike Inchalik said that "this is by far and away the lowest quality" video that the company has dealt with. Nafzger praised Lowry for restoring "crispness" to the Apollo video, which will remain in black and white and contains conservative digital enhancements. The US$230,000 restoration project took months to complete and did not include sound quality improvements. Some selections of restored footage in high definition have been made available on the NASA website.[130]

Blueprints

Grumman appears to have destroyed most of its LM documentation,[121][131] but copies exist in microfilm for the blueprints for the Saturn V.[132]

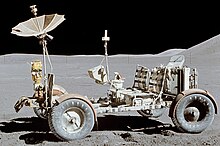

Four mission-worthy Lunar Roving Vehicles (LRV) were built by Boeing.[133] Three of them were carried to the Moon on Apollos 15, 16, and 17, used by the astronauts for transportation on the Moon, and left there. After Apollo 18 was canceled, the other LRV was used for spare parts for the Apollos 15 to 17 missions. The 221-page operation manual for the LRV contains some detailed drawings,[134] although not the blueprints.

NASA technology compared to USSR

Bart Sibrel cites the relative level of the United States and USSR space technology as evidence that the Moon landings could not have happened. For much of the early stages of the Space Race, the USSR was ahead of the United States, yet in the end, the USSR was never able to fly a crewed spacecraft to the Moon, let alone land one on the surface. It is argued that, because the USSR was unable to do this, the United States should have also been unable to develop the technology to do so.

For example, he claims that, during the Apollo program, the USSR had five times more crewed hours in space than the United States, and notes that the USSR was the first to achieve many of the early milestones in space: the first artificial satellite in orbit (October 1957, Sputnik 1);[d] the first living creature in orbit (a dog named Laika, November 1957, Sputnik 2); the first man in space and in orbit (Yuri Gagarin, April 1961, Vostok 1); the first woman in space (Valentina Tereshkova, June 1963, Vostok 6); and the first spacewalk (Alexei Leonov in March 1965, Voskhod 2).

However, most of the Soviet gains listed above were matched by the United States within a year, and sometimes within weeks. In 1965, the United States started to achieve many firsts (such as the first successful space rendezvous), which were important steps in a mission to the Moon. Furthermore, NASA and others say that these gains by the Soviets are not as impressive as they seem; that a number of these firsts were mere stunts that did not advance the technology greatly, or at all, e.g., the first woman in space.[135][136] In fact, by the time of the launch of the first crewed Earth-orbiting Apollo flight (Apollo 7), the USSR had made only nine spaceflights (seven with one cosmonaut, one with two, one with three) compared to 16 by the United States. In terms of spacecraft hours, the USSR had 460 hours of spaceflight; the United States had 1,024 hours. In terms of astronaut/cosmonaut time, the USSR had 534 hours of crewed spaceflight whereas the United States had 1,992 hours. By the time of Apollo 11, the United States had a lead much wider than that. (See List of human spaceflights, 1961–1970, and refer to individual flights for the length of time.)

Moreover, the USSR did not develop a successful rocket capable of a crewed lunar mission until the 1980s – their N1 rocket failed on all four launch attempts between 1969 and 1972.[137] The Soviet LK lunar lander was tested in uncrewed low-Earth-orbit flights three times in 1970 and 1971.

Technology used by NASA

Digital technology was in its infancy during the time of the Moon landings. The astronauts had relied on computers to aid in the Moon missions. The Apollo Guidance Computer was on the Lunar Module and the command and service module. Many computers at the time were very large despite poor specs.[138][139] For example, the Xerox Alto was released in 1973, one year after the final Moon landing.[140] This computer had 96kB of memory.[141] Most personal computers as of 2019 use 50,000 to 100,000 times this amount of RAM.[142] Conspiracy theorists claim that the computers during the time of the Moon landings would not have been advanced enough to enable space travel to the Moon and back;[143] they similarly claim that other contemporaneous technology (radio transmission, radar, and other instrumentation) was likewise insufficient for the task.[144]

Deaths of NASA personnel

In a televised program about the Moon-landing hoax allegations, Fox Entertainment Group listed the deaths of ten astronauts and two civilians related to the crewed spaceflight program as part of an alleged cover-up.

- Theodore Freeman (killed ejecting from a T-38 which had suffered a bird strike, October 1964)

- Elliot See and Charlie Bassett (T-38 crash in bad weather, February 1966)

- Virgil "Gus" Grissom, Ed White, and Roger B. Chaffee (killed in a fire during the "plugs-out test" preceding Apollo 1, January 1967)

- Edward "Ed" Givens (killed in a car accident, June 1967)

- Clifton "C. C." Williams (killed ejecting from a T-38, October 1967)

- Michael J. "Mike" Adams (died in an X-15 crash, November 1967. Adams was the only pilot killed during the X-15 flight test program. He was a test pilot, not a NASA astronaut, but had flown the X-15 above 80 kilometres or 50 miles)

- Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. (killed in an F-104 crash, December 1967, shortly after being selected as a pilot with the United States Air Force's Manned Orbiting Laboratory (MOL) program, which was canceled in 1969)

- Thomas Ronald Baron (North American Aviation employee. Baron died in an automobile collision with a train, April 27, 1967, six days after testifying before Rep. Olin E. Teague's House Subcommittee on NASA Oversight hearings held following the Apollo 1 fire, after which he was fired)

Two of the above, X-15 pilot Mike Adams and MOL pilot Robert Lawrence, had no connection with the civilian crewed space program that oversaw the Apollo missions. Baron was a quality control inspector who wrote a report critical of the Apollo program and was an outspoken critic of NASA's safety record after the Apollo 1 fire. Baron and his family were killed as their car was struck by a train at a train crossing. The deaths were an accident.[145][146] All of the deaths occurred at least 20 months before Apollo 11 and subsequent flights.

As of June 2024[update], four of the twelve Apollo astronauts who landed on the Moon between 1969 and 1972 are still alive, including Buzz Aldrin. Also, two of the twelve Apollo astronauts who flew to the Moon without landing between 1968 and 1972 are still alive.

The number of deaths within the American astronaut corps during the run-up to Apollo and during the Apollo missions is similar to the number of deaths incurred by the Soviets. During the period 1961 to 1972, at least eight Soviet serving and former cosmonauts died:

- Valentin Bondarenko (ground training accident, March 1961)

- Grigori Nelyubov (suicide, February 1966)

- Vladimir Komarov (Soyuz 1 accident, April 1967)

- Yuri Gagarin (MiG-15 crash, March 1968)

- Pavel Belyayev (complications following surgery, January 1970)

- Georgi Dobrovolski, Vladislav Volkov, and Viktor Patsayev (Soyuz 11 accident, June 1971)

Additionally, the overall chief of their crewed-spaceflight program, Sergei Korolev, died while undergoing surgery in January 1966.

Post flight conference

During the post flight conference for Apollo 11, there were moments in which the astronauts appeared serious or tired in a press conference otherwise filled with laughter. Conspiracy theorists often present images of those moments and portray it as the astronauts feeling guilty about faking the landing. This supposed evidence can be explained as a case of cherry picking and an appeal to emotion.[147][148]

NASA response

In June 1977, NASA issued a fact sheet responding to recent claims that the Apollo Moon landings had been hoaxed.[149] The fact sheet is particularly blunt and regards the idea of faking the Moon landings to be preposterous and outlandish. NASA refers to the rocks and particles collected from the Moon as being evidence of the program's legitimacy, as they claim that these rocks could not have been formed under conditions on Earth. NASA also notes that all of the operations and phases of the Apollo program were closely followed and under the scrutiny of the news media, from liftoff to splashdown. NASA responds to Bill Kaysing's book, We Never Went to the Moon, by identifying one of his claims of fraud regarding the lack of a crater left on the Moon's surface by the landing of the lunar module, and refuting it with facts about the soil and cohesive nature of the surface of the Moon.

The fact sheet was reissued on February 14, 2001, the day before Fox television's broadcast of Conspiracy Theory: Did We Land on the Moon? The documentary reinvigorated the public's interest in conspiracy theories and the possibility that the Moon landings were faked, which has provoked NASA to once again defend its name.

Alleged Stanley Kubrick involvement

Filmmaker Stanley Kubrick is accused of having produced much of the footage for Apollos 11 and 12, presumably because he had just directed 2001: A Space Odyssey, which is partly set on the Moon and featured advanced special effects.[150] It has been claimed that when 2001 was in post-production in early 1968, NASA secretly approached Kubrick to direct the first three Moon landings. The launch and splashdown would be real but the spacecraft would stay in Earth orbit and fake footage broadcast as "live from the Moon." No evidence was offered for this theory, which overlooks many facts. For example, 2001 was released before the first Apollo landing and Kubrick's depiction of the Moon's surface differs greatly from its appearance in the Apollo footage. The movement of characters on the Moon in 2001 differs from that of the filmed movement of Apollo astronauts and does not resemble an environment with 1/6 the gravity of Earth. Several scenes in 2001 show dust billowing as spacecraft landed, something that would not happen in the vacuum environment of the Moon. Kubrick did hire Frederick Ordway and Harry Lange, both of whom had worked for NASA and major aerospace contractors, to work with him on 2001. Kubrick also used some 50 mm f/0.7 lenses that were left over from a batch made by Zeiss for NASA. However, Kubrick only got this lens for Barry Lyndon (1975). The lens was originally a still photo lens and needed changes to be used for motion filming.

The mockumentary based on this idea, Dark Side of the Moon, could have fueled the conspiracy theory. This French mockumentary, directed by William Karel, was originally aired on Arte channel in 2002 with the title Opération Lune. It parodies conspiracy theories with faked interviews, stories of assassinations of Stanley Kubrick's assistants by the CIA, and a variety of conspicuous mistakes, puns, and references to old movie characters, inserted through the film as clues for the viewer. Nevertheless, Opération Lune is still taken at face value by some conspiracy believers.

An article titled "Stanley Kubrick and the Moon Hoax" appeared on Usenet in 1995, in the newsgroup "alt.humor.best-of-usenet". One passage – on how Kubrick was supposedly coerced into the conspiracy – reads:

NASA further leveraged their position by threatening to publicly reveal the heavy involvement of Mr. Kubrick's younger brother, Raul, with the American Communist Party. This would have been an intolerable embarrassment to Mr. Kubrick, especially since the release of Dr. Strangelove.

Kubrick had no such brother – the article was a spoof, complete with a giveaway sentence describing Kubrick shooting the moonwalk "on location" on the Moon. Nevertheless, the claim was taken up in earnest;[151] Clyde Lewis used it almost word-for-word,[150] whereas Jay Weidner gave the brother a more senior status within the party:

No one knows how the powers-that-be convinced Kubrick to direct the Apollo landings. Maybe they had compromised Kubrick in some way. The fact that his brother, Raul Kubrick, was the head of the American Communist Party may have been one of the avenues pursued by the government to get Stanley to cooperate.[152]

In July 2009, Weidner posted on his webpage "Secrets of the Shining", where he states that Kubrick's The Shining (1980) is a veiled confession of his role in the scam project.[153][154] This thesis was the subject of refutation in an article published on Seeker nearly half a year later.[155]

The 2015 movie Moonwalkers is a fictional account of a CIA agent's claim of Kubrick's involvement.

In December 2015, a video surfaced which allegedly shows Kubrick being interviewed shortly before his 1999 death; the video purportedly shows the director confessing to T. Patrick Murray that the Apollo Moon landings had been faked.[156] Research quickly found, however, that the video was a hoax.[157]

Academic work

In 2002, NASA granted $15,000 to James Oberg to write a point-by-point rebuttal of the hoax claims. However, NASA canceled the commission later that year, after complaints that the book would dignify the accusations.[158] Oberg said that he meant to finish the book.[158][159] In November 2002, Peter Jennings said that "NASA is going to spend a few thousand dollars trying to prove to some people that the United States did indeed land men on the Moon", and "NASA had been so rattled" that they hired somebody to write a book refuting the conspiracy theorists. Oberg says that belief in the hoax theories is not the fault of the conspiracists, but rather that of teachers and people who should provide information to the public—especially NASA.[158]

In 2004, Martin Hendry and Ken Skeldon of the University of Glasgow were awarded a grant by the UK-based Particle Physics and Astronomy Research Council to investigate Moon landing conspiracy theories.[160] In November 2004, they gave a lecture at the Glasgow Science Centre where the top ten claims by conspiracists were individually addressed and refuted.[161]

MythBusters special

An episode of MythBusters in August 2008 was dedicated to the Moon landings. The MythBusters crew tested many of the conspiracists' claims. Some of the testings were done in a NASA training facility. All of the conspiracists' claims examined on the show were labeled as having been "Busted", or disproved.

Third-party evidence of Moon landings

Imaging the landing sites

Moon-landing conspiracists claim that observatories and the Hubble Space Telescope should be able to photograph the landing sites. This implies that the world's major observatories (as well as the Hubble Program) are complicit in the hoax by refusing to take photos of the landing sites. Photos of the Moon have been taken by Hubble, including at least two Apollo landing sites, but the Hubble resolution limits viewing of lunar objects to sizes no smaller than 55–69 m (60–75 yd), which is insufficient resolution to see any landing site features.[163]

In April 2001, Leonard David published an article on space.com,[164][165] which showed a photo taken by the Clementine mission showing a diffuse dark spot at the site NASA says is the Apollo 15 lander. The evidence was noticed by Misha Kreslavsky, of the Department of Geological Sciences at Brown University, and Yuri Shkuratov of the Kharkiv Astronomical Observatory in Ukraine. The European Space Agency's SMART-1 uncrewed probe sent back photos of the landing sites, according to Bernard Foing, Chief Scientist of the ESA Science Program.[166] "Given SMART-1's initial high orbit, however, it may prove difficult to see artifacts," said Foing in an interview on space.com.

In 2002, Alex R. Blackwell of the University of Hawaii pointed out that some photos taken by Apollo astronauts[165] while in orbit around the Moon show the landing sites.

The Daily Telegraph published a story in 2002 saying that European astronomers at the Very Large Telescope (VLT) would use it to view the landing sites. According to the article, Dr. Richard West said that his team would take "a high-resolution image of one of the Apollo landing sites." Marcus Allen, a conspiracist, answered that no photos of hardware on the Moon would convince him that human landings had happened.[167] The telescope was used to image the Moon and provided a resolution of 130 meters (430 ft), which was not good enough to resolve the 4.2 meters (14 ft) wide lunar landers or their long shadows.[168]

The Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) launched their SELENE Moon orbiter on September 14, 2007 (JST), from Tanegashima Space Center. SELENE orbited the Moon at about 100 km (62 miles) altitude. In May 2008, JAXA reported detecting the "halo" generated by the Apollo 15 Lunar Module engine exhaust from a Terrain Camera image.[169] A three-dimensional reconstructed photo also matched the terrain of an Apollo 15 photo taken from the surface.

On July 17, 2009, NASA released low-resolution engineering test photos of the Apollo 11, Apollo 14, Apollo 15, Apollo 16 and Apollo 17 landing sites that have been photographed by the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter as part of the process of starting its primary mission.[170] The photos show the descent stage of the landers from each mission on the Moon's surface. The photo of the Apollo 14 landing site also shows tracks made by an astronaut between a science experiment (ALSEP) and the lander.[170] Photos of the Apollo 12 landing site were released by NASA on September 3, 2009.[171] The Intrepid lander descent stage, experiment package (ALSEP), Surveyor 3 spacecraft, and astronaut footpaths are all visible. While the LRO images have been enjoyed by the scientific community as a whole, they have not done anything to convince conspiracists that the landings happened.[172]

On September 1, 2009, India's lunar mission Chandrayaan-1 took photos of the Apollo 15 landing site and tracks of the lunar rovers.[173][174] The Indian Space Research Organisation launched their uncrewed lunar probe on September 8, 2008 (IST), from Satish Dhawan Space Centre. The photos were taken by a hyperspectral camera fitted as part of the mission's image payload.[173]

China's second lunar probe, Chang'e 2, which was launched in 2010, can photograph the lunar surface with a resolution of up to 7 m (23 ft). It spotted traces of the Apollo landings.[175]

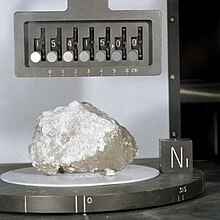

Moon rocks

The Apollo program collected 380 kg (838 lb) of Moon rocks during the six crewed missions. Analyses by scientists worldwide all agree that these rocks came from the Moon[citation needed] – no published accounts in peer-reviewed scientific journals exist that dispute this claim. The Apollo samples are easily distinguishable from both meteorites and Earth rocks[8] in that they show a lack of hydrous alteration products, they show evidence of having undergone impact events on an airless body, and they have unique geochemical traits. Furthermore, most are more than 200 million years older than the oldest Earth rocks. The Moon rocks also share the same traits as Soviet samples.[176]

Conspiracists argue that Marshall Space Flight Center Director Wernher von Braun's trip to Antarctica in 1967 (about two years before the Apollo 11 launch) was to gather lunar meteorites to be used as fake Moon rocks. Because von Braun was a former SS officer (though one who had been detained by the Gestapo),[177] the documentary film Did We Go?[122] suggests that he could have been pressured to agree to the conspiracy to protect himself from recriminations over his past. NASA said that von Braun's mission was "to look into environmental and logistic factors that might relate to the planning of future space missions, and hardware."[178]

It is now accepted by the scientific community that rocks have been blasted from both the Martian and lunar surface during impact events, and that some of these have landed on the Earth as meteorites.[179][180] However, the first Antarctic lunar meteorite was found in 1979, and its lunar origin was not recognized until 1982.[181] Furthermore, lunar meteorites are so rare that it is unlikely that they could account for the 380 kg (840 lb) of Moon rocks that NASA gathered between 1969 and 1972. Only about 30 kg (66 lb) of lunar meteorites have been found on Earth thus far, despite private collectors and governmental agencies worldwide searching for more than 20 years.[181]

While the Apollo missions gathered 380 kg (840 lb) of Moon rocks, the Soviet Luna 16, Luna 20 and Luna 24 robots gathered only 326 g (11.5 oz) combined (that is, less than one-thousandth as much). Indeed, current plans for a Martian sample return would only gather about 500 g (18 oz) of soil,[182] and a recently proposed South Pole-Aitken basin robot mission would only gather about 1 kg (2.2 lb) of Moon rock.[183][184][185]

On the makeup of the Moon rocks, Kaysing asked: "Why was there never a mention of gold, silver, diamonds or other precious metals on the moon? Wasn't this a viable consideration? Why was this fact never dicussed [sic] in the press or by the astronauts?"[186]

Missions tracked by independent parties

Aside from NASA, a number of groups and individuals tracked the Apollo missions as they happened. On later missions, NASA released information to the public explaining where and when the spacecraft could be sighted. Their flight paths were tracked using radar and they were sighted and photographed using telescopes. Also, radio transmissions between the astronauts on the surface and in orbit were independently recorded.

Retroreflectors

The presence of retroreflectors (mirrors used as targets for Earth-based tracking lasers) from the Laser Ranging Retroreflector Experiment (LRRR) is evidence that there were landings.[187] Lick Observatory attempted to detect from Apollo 11's retroreflector while Armstrong and Aldrin were still on the Moon but did not succeed until August 1, 1969.[188] The Apollo 14 astronauts deployed a retroreflector on February 5, 1971, and McDonald Observatory detected it the same day. The Apollo 15 retroreflector was deployed on July 31, 1971, and was detected by McDonald Observatory within a few days.[189] Smaller retroreflectors were also put on the Moon by the Russians; they were attached to the uncrewed lunar rovers Lunokhod 1 and Lunokhod 2.[190]

Public opinion

In a 1994 poll by The Washington Post, 9% of the respondents said that it was possible that astronauts did not go to the Moon and another 5% were unsure.[191] A 1999 Gallup Poll found that 6% of the Americans surveyed doubted that the Moon landings happened and that 5% of those surveyed had no opinion,[192][193][194][195] which roughly matches the findings of a similar 1995 Time/CNN poll.[192] Officials of the Fox network said that such skepticism rose to about 20% after the February 2001 airing of their network's television special, Conspiracy Theory: Did We Land on the Moon?, seen by about 15 million viewers.[193] This Fox special is seen as having promoted the hoax claims.[196][197]

A 2000 poll conducted by the Public Opinion Foundation (ФОМ) in Russia found that 28% of those surveyed did not believe that American astronauts landed on the Moon, and this percentage is roughly equal in all social-demographic groups.[198][199][200] In 2009, a poll held by the United Kingdom's Engineering & Technology magazine found that 25% of those surveyed did not believe that men landed on the Moon.[201] Another poll gives that 25% of 18- to 25-year-olds surveyed were unsure that the landings happened.[202]

There are subcultures worldwide which advocate the belief that the Moon landings were faked. By 1977 the Hare Krishna magazine Back to Godhead called the landings a hoax, claiming that, since the Sun is 150 million km (93 million mi) away, and "according to Hindu mythology the Moon is 800,000 miles [1,300,000 km] farther away than that", the Moon would be nearly 94 million mi (151 million km) away; to travel that span in 91 hours would require a speed of more than a million miles per hour, "a patently impossible feat even by the scientists' calculations."[203][204]

James Oberg of ABC News said that the conspiracy theory is taught in many Cuban schools, both in Cuba and where Cuban teachers are loaned.[158][205] A poll conducted in the 1970s by the United States Information Agency in several countries in Latin America, Asia, and Africa found that most respondents were unaware of the Moon landings, many of the others dismissed them as propaganda or science fiction, and many thought that it had been the Russians that landed on the Moon.[206]

In 2019, Ipsos conducted a study for C-SPAN to assess the level of belief that the 1969 Moon landing was faked. Six percent of respondents believed it was not real, but eleven percent of millennials (reached adulthood in the early 21st century) were the most likely to believe it was not factual.[207]

Summary of public opinion polls

| Dates

conducted |

Pollster | Area and Demographics | Sample

size |

Real | Faked | Unsure/No Opinion | Link(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1994 | The Washington Post | United States | 86% | 9% | 5% | [191] | |

| 1999 | Gallup Poll | United States | 89% | 6% | 5% | [192] | |

| 2000 | Public Opinion Foundation | Russia | 72% | 28% | - | [198][199][200] | |

| 2009 | Engineering & Technology | 75% | 25% | - | [201] | ||

| 2009 | Astronomy | United Kingdom, 18-25 year olds | 75% | 25% | - | [202] | |

| 2019 | C-SPAN/Ipsos | United States, Millennials | 89% | 11% | - | [208] |

See also

- Astronauts Gone Wild – 2004 film by Bart Sibrel

- In the Shadow of the Moon – 2007 British documentary film by David Sington

- Lost Cosmonauts – Conspiracy theory about Soviet cosmonauts

- List of topics characterized as pseudoscience

- Stolen and missing Moon rocks

Notes

- ^ In 1968, Clarke and Kubrick had collaborated on the film 2001: A Space Odyssey, which realistically portrayed a Moon mission.

- ^ He does this in his site as well

- ^ This number includes the crews of Apollos 8, 10, and 13, though the last technically only performed a fly-by. These three missions account for only six additional astronauts because James Lovell orbited the Moon twice (Apollos 8 and 13), while John Young and Gene Cernan orbited on Apollo 10, and both later landed on the Moon.

- ^ According to the 2007 NOVA episode "Sputnik Declassified," the United States could have launched the Explorer 1 probe before Sputnik, but the Eisenhower administration hesitated, first because they were not sure if international law meant that national borders kept going all the way into orbit (and, thus, their orbiting satellite could cause an international uproar by violating the borders of dozens of nations), and second because there was a desire to see the not yet ready Vanguard satellite program, designed by American citizens, become America's first satellite rather than the Explorer program, that was mostly designed by former rocket designers from Nazi Germany. A transcript of the appropriate section from the show is available at "Sputnik's Impact on America."

Citations

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

- ^ Plait 2002, pp. 154–173

- ^ a b Neal-Jones, Nancy; Zubritsky, Elizabeth; Cole, Steve (September 6, 2011). Garner, Robert (ed.). "NASA Spacecraft Images Offer Sharper Views of Apollo Landing Sites". NASA. Goddard Release No. 11-058 (co-issued as NASA HQ Release No. 11-289). Retrieved September 22, 2011.

- ^ Robinson, Mark (July 27, 2012). "LRO slewed 19° down-Sun allowing the illuminated side of the still standing American flag to be captured at the Apollo 17 landing site. M113751661L" (Caption). LROC News System. Archived from the original on October 24, 2012. Retrieved April 29, 2013.

- ^ "Apollo Moon flags still standing, images show". BBC News. London: BBC. July 30, 2012. Retrieved April 29, 2013.

- ^ Abbey, Jennifer (July 31, 2012). "American Flags From Apollo Missions Still Standing". ABC News (Blog). New York: ABC. Retrieved April 29, 2013.

- ^ Plait, Philip C. (2002). Bad Astronomy: Misconceptions and Misuses Revealed, from Astrology to the Moon Landing "Hoax". New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0471409766.

- ^ Howell, Elizabeth; Dobrijevic, Daisy (January 25, 2022). "Moon-landing hoax still lives on. But why?". Space.com. Retrieved December 6, 2024.

- ^ a b Phillips, Tony (February 23, 2001). "The Great Moon Hoax". Science@NASA. NASA. Archived from the original on April 10, 2010. Retrieved July 30, 2012.

- ^ Kaysing 2002

- ^ Kaysing 2002, p. 30

- ^ Kaysing 2002, p. 80

- ^ Kaysing, Wendy L. "A brief biography of Bill Kaysing". BillKaysing.com. Retrieved February 28, 2013.

- ^ a b Kaysing 2002, pp. 7–8

- ^ Plait 2002, p. 157

- ^ Braeunig, Robert A. (November 2006). "Did we land on the Moon?". Rocket and Space Technology. Robert Braeunig. Archived from the original on May 22, 2013. Retrieved May 3, 2013.

- ^ Galuppini, Albino. "Hoax Theory". BillKaysing.com. Retrieved May 3, 2013.

- ^ Schadewald, Robert J. (July 1980). "The Flat-out Truth: Earth Orbits? Moon Landings? A Fraud! Says This Prophet". Science Digest. New York: Hearst Magazines. Archived from the original on January 28, 2013. Retrieved April 29, 2013.

- ^ van Bakel, Rogier (September 1994). "The Wrong Stuff". Wired. Vol. 2, no. 9. New York: Condé Nast Publications. p. 5. Retrieved August 13, 2009.

- ^ Chaikin 2007 (page needed)

- ^ Attivissimo 2013, p. 70

- ^ Dick & Launius 2007, pp. 63–64

- ^ Chaikin 2007, p. 2, "We choose to go to the Moon! We choose to go to the Moon in this decade and do the other things – not because they are easy, but because they are hard." — Kennedy speaking at Rice University, September 12, 1962.

- ^ Plait 2002, p. 173

- ^ TheFreeDictionary.com, Our Main Sources, Retrieved August 17, 2013.

- ^ ""Neil Armstrong." The Great Soviet Encyclopedia, 3rd Edition. 1970–1979. The Gale Group, Inc". The Free Dictionary [Internet]. Retrieved February 25, 2021.

... Armstrong made the historic first flight to the moon with E. Aldrin and M. Collins, from July 16 to 24, 1969, serving as commander of the spacecraft Apollo 11. A lunar module with Armstrong and Aldrin landed on the moon in the area of the Sea of Tranquility on July 20, 1969. Armstrong was the first man to set foot on the moon (July 21, 1969); he spent two hours, 21 minutes and 16 seconds outside the spacecraft. After successfully completing its program, the crew of Apollo II returned to earth. ...The Great Soviet Encyclopedia, 3rd Edition (1970–1979). 2010 The Gale Group, Inc.

- ^ ""space exploration." The Great Soviet Encyclopedia, 3rd Edition. 1970–1979. The Gale Group, Inc". The Free Dictionary [Internet]. Retrieved February 25, 2021.

... The space age. Oct. 4, 1957, the date on which the USSR launched the first artificial earth satellite, is considered the dawn of the space age. A second important date is Apr. 12, 1961, the date of the first manned space flight, by Iu. A. Gagarin, the start of man's direct penetration into space. The third historical event is the first lunar expedition, by N. Armstrong, E. Aldrin, and M. Collins (USA), July 16–24, 1969.. ...The Great Soviet Encyclopedia, 3rd Edition (1970–1979). 2010 The Gale Group, Inc.

(Warning to avoid possible confusion: At the same cited web address the Soviet-era article is preceded by a 2013 article on space exploration from The Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia) - ^ "Moon Hoax Moonmovie.com Frequently Asked Questions". Moonmovie.com. AFTH, LLC. Archived from the original on February 12, 2008. Retrieved August 26, 2009.

- ^ "Science: Waning Moon Program". Time. September 14, 1970.

- ^ "Apollo 18 through 20 – The Canceled Missions", Dr. David R. Williams, NASA, accessed July 19, 2006.

- ^ "Soviet Lunar Programs". Space Race (Online version of exhibition on view in Gallery 114). Washington, D.C.: National Air and Space Museum. Archived from the original on May 10, 2013. Retrieved November 13, 2010.

- ^ Zak, Anatoly. "Russia's space command and control infrastructure". RussianSpaceWeb.com. Anatoly Zak. Archived from the original on July 8, 2010. Retrieved November 13, 2010.

- ^ "Soviet Space Tracking Systems". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Mark Wade. Archived from the original on November 1, 2010. Retrieved November 13, 2010.

- ^ Scheaffer 2004, p. 247

- ^ "The Moon Programme That Faltered". Spaceflight. 33. London: British Interplanetary Society: 2–3. March 1991. Bibcode:1991SpFl...33....2.

- ^ Berger, Eric (May 8, 2023). "Former head of Roscosmos now thinks NASA did not land on the Moon". Ars Technica. Retrieved May 12, 2023.

- ^ Kaysing 2002, p. 71

- ^ Attivissimo 2013, p. 163

- ^ Kennedy, John F. (May 25, 1961). Special Message to Congress on Urgent National Needs (Motion picture (excerpt)). Boston, MA: John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum. Accession Number: TNC:200; Digital Identifier: TNC-200-2. Retrieved August 1, 2013.

- ^ Congress, House of Representatives, Committee on Science and Astronautics (1973). 1974 NASA Authorization Hearings (Hearing on H.R. 4567). Washington, D.C.: 93rd Congress, first session. OCLC 23229007.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bennett & Percy 2001, p. 77

- ^ Bennett & Percy 2001, pp. 330–331

- ^ Anderson, Clinton P. (January 30, 1968), Apollo 204 Accident: Report of the Committee on Aeronautical and Space Sciences, United States Senate, with Additional Views, vol. Senate Report 956, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, archived from the original on December 20, 2014

- ^ Steven-Boniecki, Dwight (2010). Live TV From the Moon. Burlington, Ontario: Apogee Books. ISBN 978-1926592169. Archived from the original on November 5, 2018. Retrieved September 14, 2014.

- ^ "Was The Apollo Moon Landing Fake?". American Patriot Friends Network (APFN). July 21, 2009. Archived from the original on May 16, 2018. Retrieved November 25, 2008.

- ^ U.S. Office of Management and Budget

- ^ Hepplewhite, T.A. The Space Shuttle Decision: NASA's Search for a Reusable Space Vehicle, chapter 4. Washington, DC: National Aeronautics and Space Administration, 1999.

- ^ Calder, Vince; Johnson, Andrew, P.E.; et al. (October 12, 2002). "Ask A Scientist". Newton. Argonne National Laboratory. Archived from the original on July 30, 2014. Retrieved August 14, 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Ramsay 2006 [page needed]

- ^ Longuski 2006, p. 102

- ^ Aaronovitch 2010, pp. 1–2, 6

- ^ "Conspiracy Theories". Penn & Teller: Bullshit!. Season 3. Episode 3. May 9, 2005. Showtime.

- ^ Barajas, Joshua (February 15, 2016). "How many people does it take to keep a conspiracy alive?". PBS NEWSHOUR. Public Broadcasting Service (PBS). Archived from the original on October 13, 2017. Retrieved July 22, 2016.

- ^ Grimes, David R (January 26, 2016). "On the Viability of Conspiratorial Beliefs". PLOS ONE. 11 (1): e0147905. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1147905G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0147905. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4728076. PMID 26812482.

- ^ Novella, Steven; Novella, Bob; Santa Maria, Cara; Novella, Jay; Bernstein, Evan (2018). The Skeptics' Guide to the Universe: How to Know What's Really Real in a World Increasingly Full of Fake. Grand Central Publishing. pp. 209–210. ISBN 978-1538760536.

- ^ a b c Windley, Jay. "Clavius: Photography – Crosshairs". Moon Base Clavius. Clavius.org. Retrieved April 20, 2013.

- ^ Windley, Jay. "Clavius: Photography – image quality". Moon Base Clavius. Clavius.org. Retrieved September 5, 2009.

- ^ "Apollo 11 Mission Photography". Lunar and Planetary Institute. Retrieved July 23, 2009.

- ^ "Space Cameras". Hasselblad in Space. Victor Hasselblad AB. Archived from the original on May 10, 2013. Retrieved May 6, 2013.

- ^ Kaysing 2002, pp. 20, 21, 22, 23

- ^ Jones, Eric M. (January 21, 2012). "Navigation Stars used in the AOT". Apollo Lunar Surface Journal. NASA. Retrieved September 28, 2014.

- ^ Carlowicz, Mike (September 28, 2011). "Where are the stars?". NASA Earth Observatory (Blog). NASA. Retrieved April 20, 2013.

- ^ Plait 2002, pp. 158–160

- ^ Woods 2008, pp. 206–207

- ^ Harrison 2012, pp. 95–96

- ^ File:Lamp-and-moon-example-2.JPG

- ^ Keel, William C. (July 2007). "The Earth and Stars in the Lunar Sky". Skeptical Inquirer. 31 (4). Amherst, NY: Committee for Skeptical Inquiry: 47–50.

- ^ Keel, William C. "Apollo16EarthID.gif" (GIF). UA Astronomy Home Page. Retrieved May 8, 2013. Base image: AS16-123-19657; Earth image start: 1233 CDT 21 April 1972; Field shown: 18.9 degrees.

- ^ "Solar corona photographed from Apollo 15 one minute prior to sunrise". JSC Digital Image Collection. Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center. July 31, 1971. Photo ID: AS15-98-13311. Archived from the original on February 17, 2013. Retrieved April 26, 2013.

- ^ Lunsford, Danny Ross; Jones, Eric M. (2007). "Venus over the Apollo 14 LM". Apollo Lunar Surface Journal. NASA. Archived from the original on May 6, 2008. Retrieved May 8, 2013.

- ^ Plait 2002, pp. 167–172

- ^ Goddard, Ian Williams (February 26, 2001). "Goddard's Journal: Are Apollo Moon Photos Fake?". Iangoddard.com. Retrieved November 25, 2008.

- ^ a b c Bara, Michael; Troy, Steve. "Who Mourns For Apollo? Part II" (PDF). Mr. Clintberg's Studyphysics!. LunarAnomalies.com. Retrieved November 13, 2010. Part I with Steve Troy and Richard C. Hoagland is available here (PDF). Part III by Steve Troy has been archived from the original by the Wayback Machine on June 10, 2009.