88th Infantry Division (United States)

| 88th Division 88th Infantry Division | |

|---|---|

88th Infantry Division shoulder sleeve insignia. | |

| Active | 1917–1919 1921–1947 |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Infantry |

| Size | Division |

| Nickname(s) | "Fighting Blue Devils" "Clover Leaf Division" |

| Engagements | World War I |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Paul Wilkins Kendall |

| Insignia | |

| Distinctive Unit Insignia |  |

The 88th Infantry Division was an infantry division of the United States Army that saw service in both World War I and World War II. It was one of the first of the Organized Reserve divisions to be called into federal service, created nearly "from scratch" after the implementation of the draft in 1940. Previous divisions were composed of a core of either Regular Army or National Guard personnel plus draftees. Much of the experience in reactivating it was used in the subsequent expansion of the U.S. Army.

By the end of World War II the 88th Infantry fought its way to the northernmost extreme of Italy. In early May 1945 troops of its 349th Infantry Regiment joined the 103d Infantry Division of the VI Corps of the U.S. Seventh Army, part of the 6th Army Group, which had raced south through Bavaria into Innsbruck, Austria, in Vipiteno in the Italian Alps.[1]

World War I

[edit]- Activated: 5 August 1917, Camp Dodge, Iowa

- Overseas: 7 September 1918

- Major operations: Did not participate as a division

- Casualties: Total-78 (KIA-12; WIA-66)

- Commanders:

- Maj. Gen. Edward H. Plummer (25 August 1917)

- Brig. Gen. Robert N. Getty (27 November 1917)

- Maj. Gen. Edward H. Plummer (19 February 1918)

- Brig. Gen. Robert N. Getty (15 March 1918)

- Brig. Gen. William D. Beach (24 May 1918)

- Maj. Gen. William Weigel (10 September 1918)

- Inactivated: 10 June 1919, Camp Dodge, Iowa

Composition

[edit]Initial personnel for the division were Selective Service men from Illinois, Iowa, Minnesota, and North Dakota, and the division was at full strength of 20,000 by the end of September 1917. The 88th Division, like many National Army divisions, subsequently suffered heavily from transfers to other new units or units that were more advanced in their training and preparing to go overseas, delaying its combat readiness. In October 1917, 3,000 men were transferred to the 34th Division and 1,000 to the 33rd Division, while in November 8,000 went to the 87th Division. The strength of the 88th Division was only 8,000 men in January 1918, but the next month, 12,000 men arrived from Iowa and Minnesota to bring the division to full strength. Subsequently, 16,000 men were transferred from the division, the majority to the 82nd Division, and others to the 30th, 33rd, 35th and 90th Divisions. At the end of April, the 88th Division was left with less than 8,500 men, but during May and June more than 10,000 fresh drafts joined, many from Missouri, Nebraska, and South Dakota, and during July, more fresh drafts and transfers completed the division. The division sailed in stages to England in August and September 1918, and moved to France. Elements of the division participated in training near the front lines with the French Army, and occupied quiet sectors of the front in Alsace beginning in early October 1918. The Armistice of 11 November 1918 ended the war a month later.

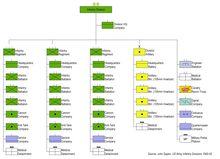

The division was composed of the following units:[2][3]

- Headquarters, 88th Division

- 175th Infantry Brigade

- 349th Infantry Regiment

- 350th Infantry Regiment

- 338th Machine Gun Battalion

- 176th Infantry Brigade

- 351st Infantry Regiment

- 352nd Infantry Regiment

- 339th Machine Gun Battalion

- 163rd Field Artillery Brigade

- Headquarters Troop, 88th Division

- 337th Machine Gun Battalion

- 338th Engineer Regiment

- 313th Field Signal Battalion

- 313th Train Headquarters and Military Police

- 313th Ammunition Train

- 313th Supply Train

- 313th Engineer Train

- 313th Sanitary Train

- 349th, 350th, 351st, and 352nd Ambulance Companies and Field Hospitals

Interwar period

[edit]The 88th Division headquarters arrived at the port of Newport News, Virginia, aboard the USS Pocahontas on 1 June 1919 and was demobilized on 10 June 1919 at Camp Dodge. Pursuant to the National Defense Act of 1920, the 88th Division was reconstituted in the Organized Reserve on 24 June 1921, allotted to the Seventh Corps Area, assigned to the XVII Corps, and further allotted to the states of Minnesota, Iowa, and North Dakota. The division headquarters was organized on 2 September 1921 at 1684 Van Buren Street in St. Paul, Minnesota. It was relocated to the Kasota Building in Minneapolis, Minnesota, on 29 September 1921, to 835 Palace Building in August 1924, and to the new Post Office Building in July 1937, where it remained until activated for World War II. In the first years after World War I, many officers of the division were chaplains, doctors, engineers, or other men with prior military service commissioned directly from civilian life. As the 1920s turned to the 1930s, many of the World War I veteran officers began to retire, and the single largest cohort of officers in the division became college graduates from the Reserve Officers Training Corps. The primary sources for these new Reserve lieutenants were Coe College, the State University of Iowa, and Iowa State College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts in Iowa, the University of Minnesota in Minnesota, and North Dakota Agricultural College and the University of North Dakota in North Dakota.[4]

The designated mobilization and training station for the division was Camp Dodge. For annual training the headquarters and staff usually trained with the staff of the 14th Infantry Brigade, either at Fort Crook, Nebraska, or Fort Snelling, Minnesota. The infantry regiments held their annual training primarily with the 3rd Infantry Regiment at Fort Snelling, or with the 17th Infantry Regiment at Fort Des Moines, Iowa. Other units, such as the special troops, artillery, engineers, aviation, medical, and quartermaster, trained at various posts in the Sixth and Seventh Corps Areas, often with the active units of the 7th Division or other Regular Army units. For example, the division artillery trained at Camp McCoy, Wisconsin; the 313th Engineer Regiment trained at Fort Riley, Kansas, with Troop A, 9th Engineer Squadron; the 313th Medical Regiment trained at the medical corps training camp at Fort Snelling; and the 313th Observation Squadron trained with the 16th Observation Squadron at Marshall Field, Kansas. The infantry regiments also rotated responsibility to conduct the Citizens Military Training Camps held at Fort Snelling, Fort Des Moines, and Fort Lincoln, North Dakota, each year. The division sometimes participated in Seventh Corps Area and Fourth Army command post exercises with other Regular Army, National Guard, and Organized Reserve units, but unlike the Regular and Guard units, the 88th Division did not participate in the Seventh Corps Area maneuvers and the Fourth Army maneuvers of 1937, 1940, and 1941 as an organized unit due to lack of enlisted personnel and equipment. Instead, the officers and a few enlisted reservists were assigned to Regular and Guard units to bring the units up to war strength for the exercises. Additionally, some were assigned duties as umpires or as support personnel.[5] In the United States Army's precautionary mobilization in 1940-1941 prior to the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, most Organized Reserve officers were ordered to active duty individually and assigned to fill vacancies in existing or newly organized Regular Army and National Guard units. As a result, the 88th Division was almost completely depleted of personnel, particularly company-grade officers (lieutenants and captains).

World War II

[edit]- Ordered into active military service: 15 July 1942, Camp Gruber, Oklahoma

- Overseas: 6 December 1943

- Distinguished Unit Citations: 3

- Campaigns: Rome-Arno, North Apennines, Po Valley

- Days of combat: 344

- Awards: Medal of Honor-3 ; Distinguished Service Cross (United States)-40 ; Distinguished Service Medal (United States)-2 ; Silver Star-522; Legion of Merit-66; Soldier's Medal-19 ; Bronze Star Medal-3,784.

- Unit citations: Third Battalion, 351st Infantry Regiment (action vicinity Laiatico; 9–13 July 1944). Second Battalion, 350th Infantry Regiment (action on Mt. Battaglia, 27 Sept – 3 Oct 1944). Second Battalion, 351st Infantry Regiment (action vicinity Mt. Cappello, 27 Sept – 1 Oct 1944).

- Commanders:

- Maj. Gen. John E. Sloan (July 1942 – September 1944)

- Maj. Gen. Paul W. Kendall (September 1944 – July 1945)

- Brig. Gen. James C. Fry (July–November 1945)

- Maj. Gen. Bryant Moore (November 1945 to inactivation)

- Inactivated: 24 October 1947 in Italy

Activation and training

[edit]Before Organized Reserve infantry divisions were ordered into active military service, they were reorganized on paper as "triangular" divisions under the 1940 tables of organization. The headquarters companies of the two infantry brigades were consolidated into the division's cavalry reconnaissance troop, and one infantry regiment was removed by inactivation. The field artillery brigade headquarters and headquarters battery became the headquarters and headquarters battery of the division artillery. Its three field artillery regiments were reorganized into four battalions; one battalion was taken from each of the two 75 mm gun regiments to form two 105 mm howitzer battalions, the brigade's ammunition train was reorganized as the third 105 mm howitzer battalion, and the 155 mm howitzer battalion was formed from the 155 mm howitzer regiment. The engineer, medical, and quartermaster regiments were reorganized into battalions. In 1942, divisional quartermaster battalions were split into ordnance light maintenance companies and quartermaster companies, and the division's headquarters and military police company, which had previously been a combined unit, was split.[6]

The 88th Infantry Division, commanded by Major General John E. Sloan, was ordered into active military service on 15 July 1942 at Camp Gruber, Oklahoma, around a cadre of officers and men from the 9th Infantry Division, National Guard and Organized Reserve officers, and men from infantry replacement training centers at Camp Wheeler, Georgia, and Camp Wolters, Texas. The first group of draftee fillers for the division arrived in early August, coming predominantly from New England and the Mid-Atlantic states. Other groups, mainly from the Great Lakes and Midwest but also hailing from the Southwest and Far West, arrived in October and early November to round out the division.

The division was unique among U.S. Army infantry divisions during World War II in that it suffered relatively little from factors that caused personnel turbulence or other delays to the date on which it was judged to be "ready" for combat service and shipped to a theater of war.[7] The Army's officer candidate schools (OCS) expanded dramatically in scope in 1942. One requirement for entry was that men have at least six months of service in the Army; the majority of the 88th Infantry Division's personnel did not become eligible for OCS until January 1943, around which time the Army reconsidered the troop basis, eliminating the need for many infantry officers as their future units were no longer contemplated for organization. OCS quotas in the combat arms were reduced dramatically until 1944.[8] There was also little pressure for the division to provide candidates for the Army Specialized Training Program (ASTP), which went into operation early in 1943, as units on maneuvers or under alert orders were exempted from providing candidates. The 88th Infantry Division went on maneuvers in Louisiana beginning in June 1943 and was alerted for overseas movement in September, soon after completing them.[9] The division also had not progressed far enough in its training to be a victim of the stripping of stateside units in 1942 to obtain men needed to fill out units slated for participation in the Allied landings in North Africa in November 1942. In addition, it moved overseas just as the stripping of stateside units to fill emergency requirements and provide additional sources of trained replacements became a formalized policy beginning in fall 1943, resulting in near-continuous personnel losses to many units until late summer 1944.[10] According to the Army Ground Forces, the 88th's three sister divisions activated in July 1942, the 80th, 89th, and 95th, respectively lost seven, fourteen, and eight months of training time to personnel turbulence caused by withdrawal of ASTP/OCS candidates or time lost because of other factors not attributed to personnel turbulence.[11]

Combat chronicle

[edit]- First Entered combat: Advance party on night of 3–4 January 1944 in support of Monte Cassino attacks.[12]

- First Organization Committed to Line: 2nd Battalion, 351st Infantry Regiment plus attachments[13]

- First combat fatality: 3 January 1944

- Began post war POW Command: 7 June 1945. Responsible for guarding and later repatriating 324,462 German POWs.[14]

The 88th Infantry Division arrived at Casablanca, French Morocco on 15 December 1943, and moved to Magenta, Algeria, on 28 December for intensive training. Destined to spend the war fighting on the Italian Front, the division arrived at Naples, Italy on 6 February 1944, and concentrated around Piedimonte d'Alife for combat training. The 88th Infantry Division, along with the 85th Infantry Division, were the first United States Army divisions composed essentially entirely of draftees to enter combat. An advance element went into the line before Monte Cassino on 27 February, and the entire division relieved the battered British 46th Infantry Division along the Garigliano River in the Minturno area on 5 March. A period of defensive patrols and training followed. The 88th formed part of Major General Geoffrey Keyes's II Corps, part of the U.S. Fifth Army, under Lieutenant General Mark W. Clark.

After being inspected by the Fifth Army commander on 5 May, the 88th Division, six days later, drove north to take Spigno, Mount Civita, Itri, Fondi, and Roccagorga, reached Anzio, 29 May, and pursued the enemy into Rome, being the first unit of the Fifth Army into the city on 4 June, two days before the Normandy landings, after a stiff engagement on the outskirts of the city. An element of the 88th is credited with being first to enter the Eternal City. After continuing across the Tiber to Bassanelio the 88th retired for rest and training, 11 June. The division went into defensive positions near Pomerance on 5 July, and launched an attack toward Volterra on the 8th, taking the town the next day. Laiatico fell on the 11th, Villamagna on the 13th, and the Arno River was crossed on the 20th although the enemy resisted bitterly.

After a period of rest and training, the 88th Division, now commanded by Major General Paul Wilkins Kendall, opened its assault on the Gothic Line on 21 September, and advanced rapidly along the Firenzuola-Imola road, taking Monte Battaglia (Casola Valsenio, RA) in the Battle of Monte Battaglia on the 28th. The enemy counterattacked savagely and heavy fighting continued on the line toward the Po Valley. The strategic positions of Mount Grande and Farnetto were taken on 20 and 22 October. From 26 October 1944 to 12 January 1945, the 88th entered a period of defensive patrolling in the Mount Grande-Mount Cerrere sector and the Mount Fano area. From 24 January to 2 March 1945, the division defended the Loiano-Livergnano area and after a brief rest returned to the front. The drive to the Po Valley began on 15 April. Monterumici fell on the 17th after an intense artillery barrage and the Po River was crossed at Revere-Ostiglia on 24-25 April, as the 88th pursued the enemy toward the Alps. The cities of Verona and Vicenza were captured on the 25th and 28th and the Brenta River was crossed on 30 April. The 88th was driving through the Dolomite Alps toward Innsbruck, Austria where it linked up with the 103rd Infantry Division, part of the U.S. Seventh Army, when the hostilities ended on 2 May 1945.[1] The end of World War II in Europe came six days later. Throughout the war the 88th Infantry Division was in combat for 344 days.

Casualties

[edit]- Total battle casualties: 13,111[15]

- Killed in action: 2,298[15]

- Wounded in action: 9,225[15]

- Missing in action: 941[15]

- Prisoner of war: 647[15]

Units

[edit]

Units assigned to the division during World War II included:

- Headquarters, 88th Infantry Division

- 349th Infantry Regiment

- 350th Infantry Regiment

- 351st Infantry Regiment

- Headquarters and Headquarters Battery, 88th Infantry Division Artillery

- 337th Field Artillery Battalion (105mm)

- 338th Field Artillery Battalion (105mm)

- 339th Field Artillery Battalion (155mm)

- 913th Field Artillery Battalion (105mm)

- 313th Engineer Combat Battalion

- 313th Medical Battalion

- 88th Cavalry Reconnaissance Troop (Mechanized)

- Headquarters, Special Troops, 88th Infantry Division

- 788th Ordnance Light Maintenance Company

- 88th Quartermaster Company

- 88th Signal Company

- Military Police Platoon

- Band

- 88th Counterintelligence Corps Detachment

Post war

[edit]After the war, the 88th Infantry Division absorbed some personnel and units from the 34th Infantry Division and served on occupation duty in Italy guarding the Morgan Line from positions in Italy and Trieste until 15 September 1947 when the Italian peace treaty came into force. The 351st Infantry was relieved from assignment to the division on 1 May 1947 and served as temporary military Government of the Free Territory of Trieste, securing the new independent State[16] between Italy and Yugoslavia on behalf of the United Nations Security Council.[17] Designated TRUST (Trieste United States Troops), the command served as the front line in the Cold War from 1947 to 1954, including confrontations with Yugoslavian forces.

In October 1954 the mission ended upon the signing of the Memorandum of Understanding of London[18] establishing a temporary civil administration in the Anglo-American Zone of the Free Territory of Trieste, entrusted to the responsibility of the Italian Government.[19]

TRUST units, which included a number of 88th divisional support units, all bore a unit patch which was the coat of arms of the Free Territory of Trieste superimposed over the divisional quatrefoil, over which was a blue scroll containing the designation "TRUST" in white.

Cold War and beyond

[edit]The 88th Army Reserve Command (ARCOM) was formed at Fort Snelling in January 1968, as one of 18 ARCOMs which were organized to provide command and control to Army Reserve units.[20][21] The initial area of responsibility for the 88th ARCOM included Minnesota and Iowa, and this area was later expanded to include Wisconsin. Army Reserve Commands were authorized to use the number and shoulder sleeve insignia of infantry divisions with the same number. However, ARCOMs did not inherit the lineage and honors of the divisions because it was against Department of the Army policy for a Table of Distribution and Allowances organization, such as an ARCOM, to perpetuate the lineage and honors of a Table of Organization and Equipment formation, like the 88th Infantry Division.

In 1996, when the Army Reserve's command structure was revised, the 88th Regional Support Command (88th RSC) was established at Fort Snelling. Its mission was to command and control Army Reserve units in a six state region, which included Minnesota, Wisconsin, Illinois, Indiana, Michigan and Ohio. In addition, the 88th RSC ensured operational readiness, provided area support services, and supported emergency operations in its area of responsibility.

In 2003, the Army Reserve's command structure was again revised, and the 88th Regional Readiness Command (88th RRC) was formed at Fort Snelling with responsibility for USAR units in the same six states included in the 88th RSC. Various Combat Support units mobilize and deploy to Operation Iraqi Freedom in late 2003-mid 2004.

In its 2005 BRAC Recommendations, DoD recommended to realign Fort Snelling, MN by disestablishing the 88th Regional Readiness Command. This recommendation was part of a larger recommendation to re-engineer and streamline the Command and Control structure of the Army Reserve that would create the Northwest Regional Readiness Command at Fort McCoy, WI.

In 2008, the 88th Regional Readiness Command (88th RRC) moved to Fort McCoy, Wisconsin. The mission was changed to provide base operations support to the new 19 state region, Welcome Home Warrior ceremonies, and the Yellow Ribbon weekends. The units assigned to the 88th RSC include 6 Army Reserve Bands and the Headquarters Company. It may supervise the 643rd Area Support Group at Whitehall, Ohio.

Operation Allies Welcome

[edit]The 88th was ordered to support Operation Allies Refuge in August 2021 as the core of Task Force McCoy. From August 2021 until February 2022, the task force assisted in feeding, housing, clothing, and providing assistance to the more than 12,600 Afghans resettling in the United States. Major subordinate elements of the task force included the Fort Mccoy Garrison, the 181st Infantry Brigade, 302nd Maneuver Enhancement Brigade, 720th MP Battalion, and the 1st Squadron, 32nd Cavalry.[22]

Current

[edit]The division shoulder patch is worn by the United States Army Reserve 88th Readiness Division at Fort Snelling, Minnesota; the division lineage is perpetuated by the 88th RD.[citation needed] RDs such as the 88th have the same number as inactivated divisions and are allowed to wear the shoulder patch, and division lineage and honors are inherited by an RD.

General

[edit]- Shoulder patch: A blue (for Infantry) quatrefoil, formed by two Arabic numeral "8s". A rocker above it with the nickname "Blue Devils" was often worn.

- During World War II, the Germans thought the 88th was an elite stormtrooper Division. This was most likely due to parallels between the "Blue Devil" nickname and patch rocker and the German SS's use of the Totenkopf death's head insignia.

Decorations

[edit]| Ribbon | Award | Year | Orders |

|---|---|---|---|

| Army Meritorious Unit Commendation | Afghanistan Retrograde 2021-2022 |  |

See also

[edit]- 1st Lieutenant James Henry Taylor

- Sgt Keith Matthew Maupin

References

[edit]- ^ a b Fifth Army History • Race to the Alps, Chapter VI : Conclusion [1] Archived 13 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine "On 3 May the 85th and 88th [Infantry] Divisions sent task forces north over ice and snow 3 feet deep to seal the Austrian frontier and to gain contact with the American Seventh Army, driving southward from Germany. The 339th Infantry [85th Division] reached Austrian soil east of Dobbiaco at 0415, 4 May; the Reconnaissance Troop, 349th Infantry [88th Division], met troops from [103rd Infantry Division] VI Corps of Seventh Army at 1051 at Vipiteno, 9 miles south of Brenner."

- ^ http://www.history.army.mil/html/books/023/23-2/CMH_Pub_23-2.pdf Archived 24 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine Order of Battle in the Great War P393

- ^ "Infantry organization and History" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 22 May 2017.

- ^ Clay, Steven E. (2010). U.S. Army Order of Battle, 1919-1941, Volume 4. The Services: Quartermaster, Medical, Military Police, Signal Corps, Chemical Warfare, and Miscellaneous Organizations, 1919-41. Fort Leavenworth, KS: Combat Studies Institute Press. p. 2,635, 2,643, 2,659, 2,666-67.

- ^ Clay, Steven E. (2010). U.S. Army Order of Battle 1919-1941 Volume 1, The Arms: Major Commands and Infantry Organizations 1919-1941 (PDF). Combat Studies Institute Press. p. 261.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Wilson 1998, pp. 161, 169–70.

- ^ Brown, John S. (1986). Draftee Division: The 88th Infantry Division in World War II. Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky. p. 12-13.

- ^ Brown, John S. (1986). Draftee Division: The 88th Infantry Division in World War II. Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky. p. 14-15.

- ^ Brown, John S. (1986). Draftee Division: The 88th Infantry Division in World War II. Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky. p. 15-16.

- ^ Brown, John S. (1986). Draftee Division: The 88th Infantry Division in World War II. Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky. p. 17-18.

- ^ Brown, John S. (1986). Draftee Division: The 88th Infantry Division in World War II. Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky. p. 167.

- ^ Delaney 1947, p. 37.

- ^ Delaney 1947, p. 45.

- ^ Delaney 1947, p. 359.

- ^ a b c d e Army Battle Casualties and Nonbattle Deaths, Final Report (Statistical and Accounting Branch, Office of the Adjutant General, 1 June 1953)

- ^ Article 21 and Annex VII, Instrument for the Provisional Regime of the Free Territory of Trieste. See: https://treaties.un.org/doc/Publication/UNTS/Volume%2049/v49.pdf

- ^ see: United Nations Security Council Resolution 16, 10 January 1947: http://www.un.org/en/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=S/RES/16(1947)

- ^ UNTS Vol.235, 3297 Memorandum of Understanding of London

- ^ Memorandum of Understanding of London, article 2: see https://treaties.un.org/doc/Publication/UNTS/Volume%20235/v235.pdf

- ^ Wilson 1998, p. [page needed].

- ^ Isby & Kamps 1985, p. 388.

- ^ https://www.army.mil/article/254323/operation_allies_welcome_concludes_at_fort_mccoy_last_afghans_depart_post#:~:text=As%20of%208%20a.m.%20Feb.%2015%2C%20the%20last,who%20assisted%20the%20United%20States%E2%80%99%20interests%20in%20Afghanistan./ Operation Allies Welcome concludes at Fort McCoy

Bibliography

- The Army Almanac: A Book of Facts Concerning the Army of the United States U.S. Government Printing Office, 1950 reproduced at http://www.history.army.mil/html/forcestruc/cbtchron/cbtchron.html Archived 21 March 2021 at the Wayback Machine.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - About Face: The Odyssey of an American Warrior, by David Hackworth: pp 35, 308.

- Brown, John Sloan. Draftee Division: the 88th Infantry Division in World War II. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 1986. ISBN 0-8131-1581-7

- Delaney, John P. (1947). The Blue Devils in Italy: a history of the 88th Infantry Division in World War II. Washington: Infantry Journal Press. OCLC 2617939. Reprinted 1988.

- Wilson, John B. (1999). Armies, Corps, Divisions, and Separate Brigades. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office. p. 197. ISBN 978-0-16-049992-0.

- Wilson, John B. (1998). Maneuver and Firepower: The Evolution of Divisions and Separate Brigades. Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History, U.S. Army. Archived from the original on 4 June 2008.

- Clay, Steven E. (2010). U.S. Army Order of Battle 1919-1941. Combat Studies Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-9841901-4-0.

- Isby, David C.; Kamps, Charles Jr. (1985). Armies of NATO's Central Front. Jane's Publishing Company.

External links

[edit]- History of the 88th Division in the Great War

- The 88th Division in the World War of 1914 – 1918

- We Were There: From Gruber to the Brenner Pass

- The battle of Cornuda, the 88th division's last battle of World War II

- Oral history interview with Nicholas Cipu, a Staff Sergeant in the 88th Infantry Division, during World War II from the Veterans History Project at Central Connecticut State University

- 752nd Tank Battalion in World War II