Boys Town (film)

| Boys Town | |

|---|---|

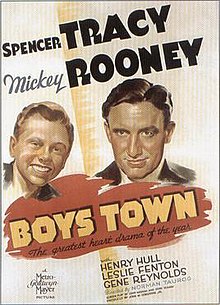

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Norman Taurog |

| Screenplay by | John Meehan Dore Schary |

| Story by | Dore Schary Eleanore Griffin |

| Based on | Life of Father Edward J. Flanagan and "Boys Town" |

| Produced by | John W. Considine Jr. |

| Starring | Spencer Tracy Mickey Rooney |

| Cinematography | Sidney Wagner |

| Edited by | Elmo Veron |

| Music by | Edward Ward |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Loew's Inc. |

Release date |

|

Running time | 93 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $772,000[1] |

| Box office | $4,058,000[1] |

Boys Town is a 1938 American biographical drama film based on Father Edward J. Flanagan's work with a group of underprivileged boys in a home/educational complex that he founded and named "Boys Town" in Nebraska. It stars Spencer Tracy as Father Edward J. Flanagan, and Mickey Rooney with Henry Hull, Leslie Fenton, and Gene Reynolds.

The film was written by Dore Schary, Eleanore Griffin, and John Meehan, and was directed by Norman Taurog. Tracy won the Academy Award for Best Actor for his performance.

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studio head Louis B. Mayer, who was a Belarusian-Canadian-American Jew known for his respect for the Catholic Church, later called this his favorite film of his long tenure at MGM.[2][3]

Although the story is largely fictional, it is based upon a real man and a real place. Boys Town is a community outside Omaha, Nebraska.[2] In 1941, MGM made a sequel, Men of Boys Town, with Spencer Tracy and Mickey Rooney reprising their roles from the earlier film.

Plot

[edit]

A convicted murderer asks to make his confession on the day of his execution. He is visited by an old friend, Father Flanagan, who runs a home for indigent men in Omaha, Nebraska. When the prison officials suggest that the condemned man owes the state a debt, Father Flanagan witnesses the condemned man's diatribe to prison officials and a reporter that describes his awful plight as a homeless and friendless boy who was a ward in state institutions. After the convicted man asks the officials to leave, Father Flanagan provides some comfort and wisdom. On the train back to Omaha, Father Flanagan is transformed in his humanitarian mission by revelations (echoed in the words) imparted by the condemned man's litany of hardships suffered as a child, without friends or family, and a ward of the state.

Father Flanagan believes there is no such thing as a bad boy and spends his life attempting to prove it. He battles indifference, the legal system, and often even the boys, to build a sanctuary that he calls Boys Town. The boys have their own government, make their own rules, and dish out their own punishment. One boy, Whitey Marsh, is as much as anyone can handle. Whitey's elder brother Joe, in prison for murder, asks Father Flanagan to take Whitey—a poolroom shark and tough-talking hoodlum—to Boys Town. Joe escapes custody during transfer to federal prison. Whitey stays, though, and runs for mayor of Boys Town, determined to win with his "don't be a sucker" campaign slogan.

Winning the election for mayor is Tony Ponessa, a disabled boy. Whitey has an outburst after finding out the results. This nearly causes a fist fight between Whitey and outgoing mayor, Freddie Fuller. Since Whitey's arrival at Boys Town, he and Freddie do not get along well. To settle their differences once and for all, a boxing match is held. Freddie defeats Whitey with Father Flanagan and all of the boys watching.

Whitey leaves Boys Town after being defeated in the boxing match. Pee Wee, the Boys Town mascot, catches up with him and pulls on his sleeve, pleading, "We're going to be pals, ain't we?" Whitey, nearly in tears, refuses and pushes the child to the ground and tells him to go back. He storms across the highway and Pee Wee follows him. Pee Wee is suddenly hit by a car; Whitey leaves, feeling guilty and hurt. During an aimless walk in downtown Omaha, Whitey runs into his brother Joe, who mistakenly shoots him in the leg. Joe takes Whitey to a church and calls Flanagan anonymously, after which Whitey is taken back to Boys Town. The sheriff comes to get Whitey, but Flanagan offers to take full responsibility for the boy.

Whitey refuses to tell Flanagan about the robbery, because he has promised Joe not to inform on him. But when he realizes that his silence could result in the end of Boys Town, he goes to Joe's hideout. Joe, realizing with Whitey that Boys Town is more important than they, releases his brother from his promise. Joe protects him until Flanagan and some boys arrive at their hideout. The criminals are recaptured and Boys Town's reward is a flood of donations. Whitey is elected the new mayor of Boys Town by acclamation and Dave Morris resigns himself to go into more debt as Flanagan tells him of his new ideas for expanding the facility.

Cast

[edit]- Spencer Tracy as Father Flanagan

- Mickey Rooney as Whitey Marsh

- Henry Hull as Dave Morris

- Leslie Fenton as Dan Farrow

- Gene Reynolds as Tony Ponessa

- Edward Norris as Joe Marsh

- Addison Richards as The Judge

- Minor Watson as The Bishop

- Jonathan Hale as John Hargraves

- Bobs Watson as Pee Wee

- Martin Spellman as Skinny

- Mickey Rentschler as Tommy Anderson

- Frankie Thomas as Freddie Fuller

- Jimmy Butler as Paul Ferguson

- Sidney Miller as Mo Kahn

- Gladden James as Doctor

- Everett Brown as Barky

- Robert Gleckler as Mr. Reynolds

- Stanley Blystone as Guard (uncredited)

- Kent Rogers as Tailor (uncredited)

Reception

[edit]Boys Town was a box office success, becoming the second highest-grossing film of 1938 and earning MGM over $2 million in profit.[4] According to MGM records, the film earned $2,828,000 in the United States and Canada, and $1,230,000 elsewhere, resulting in a profit of $2,112,000.[1]

On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds a score of 90% based on 20 reviews, with an average rating of 7.20/10.[5]

Awards and recognition

[edit]| Academy Award | Result | Winner |

|---|---|---|

| Outstanding Production | Nominated | Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (John W. Considine Jr, Producer) Winner was Frank Capra (Columbia) — You Can't Take It With You |

| Best Director | Nominated | Norman Taurog Winner was Frank Capra — You Can't Take It With You |

| Best Actor | Won | Spencer Tracy |

| Best Writing, Screenplay | Nominated | John Meehan and Dore Schary Winner was Ian Dalrymple, Cecil Arthur Lewis, W. P. Lipscomb, George Bernard Shaw – Pygmalion |

| Best Writing, Original Story | Won | Eleanore Griffin and Dore Schary |

| Recognition | ||

| American Film Institute | AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes & Villains: Father Flanagan – #42 Hero[6] | |

| AFI's 100 Years...100 Cheers - #81[7] | ||

In February 1939, when he accepted his Oscar for the role, Spencer Tracy talked about Father Flanagan in his acceptance speech. "If you have seen him through me, then I thank you." An MGM publicity representative mistakenly announced that Tracy was donating his Oscar to Flanagan, not having confirmed it with Tracy. Tracy said: "I earned the ... thing. I want it." The Academy hastily struck another inscription, Tracy kept his statuette, and Boys Town got one, too. It read: "To Father Flanagan, whose great humanity, kindly simplicity, and inspiring courage were strong enough to shine through my humble effort. Spencer Tracy."[8]

Home media

[edit]Boys Town was released on VHS by MGM on March 29, 1993, and re-released on VHS on March 7, 2000. On November 8, 2005, it was released on DVD as a part of the "Warner Brothers Classic Holiday Collection", a three-DVD set which also contains Christmas in Connecticut and the 1938 version of A Christmas Carol, and as an individual disc. The DVD release also includes the 1941 sequel Men of Boys Town as an extra feature.

Sequel

[edit]Released in April 1941, Men of Boys Town takes a darker view of the issue of homeless and troubled youth. Tracy and Rooney reprise their characters as Father Flanagan and Whitey Marsh as they expose the conditions in a boys reform school. This film was released on VHS on December 23, 1993, but is now available only as an extra feature on Boys Town DVD.

Popular culture

[edit]In the Northern Exposure television series 1991 episode "The Big Kiss", orphan Ed Chigliak watches Boys Town and is inspired to find out who his real parents are. He mentions the film reference to several other characters.

Newt Gingrich, the Speaker of the House of Representatives in 1994, referred to the film to argue that philanthropists would be able to help those people and organizations affected by government cuts.[9]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c The Eddie Mannix Ledger, Los Angeles: Margaret Herrick Library, Center for Motion Picture Study.

- ^ a b Clooney, Nick (November 2002). The Movies That Changed Us: Reflections on the Screen. New York: Atria Books, a trademark of Simon & Schuster. p. 205. ISBN 0-7434-1043-2.

- ^ "The Religious Affiliation of Movie Producer Louis B. Mayer". Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved October 16, 2012.

- ^ James Curtis, Spencer Tracy: A Biography, Alfred Knopf, 2011 p. 370

- ^ Deutsche, R. (1991), "Boys Town", Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 9 (1): 5, Bibcode:1991EnPlD...9....5D, doi:10.1068/d090005, retrieved May 17, 2022

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes & Villains". American Film Institute.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Cheers". American Film Institute. Retrieved December 13, 2023.

- ^ Clooney, pp. 212–213

- ^ "Eleanore Griffin, 91; Screenwriter Shared 'Boys Town' Oscar". The New York Times. July 30, 1995. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 22, 2016.

External links

[edit]- The Story Behind the Movie Archived November 28, 2020, at the Wayback Machine — official site

- Boys Town at IMDb

- Boys Town at the TCM Movie Database

- Boys Town at Rotten Tomatoes

- Boys Town at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- 1938 films

- 1930s biographical drama films

- American biographical drama films

- 1930s English-language films

- American black-and-white films

- Films about Catholicism

- Films about Catholic priests

- Films about Christianity

- Films set in Nebraska

- Films shot in Nebraska

- Films that won the Academy Award for Best Story

- Films featuring a Best Actor Academy Award–winning performance

- Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer films

- Films directed by Norman Taurog

- 1938 drama films

- Films scored by Edward Ward (composer)

- 1930s American films

- English-language biographical drama films