Columbia, California

Columbia | |

|---|---|

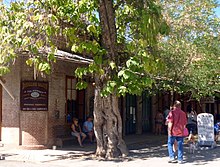

Main Street in Columbia, California | |

Location in Tuolumne County and the state of California | |

| Coordinates: 38°2′2″N 120°24′4″W / 38.03389°N 120.40111°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Tuolumne |

| Area | |

• Total | 5.98 sq mi (15.49 km2) |

| • Land | 5.96 sq mi (15.44 km2) |

| • Water | 0.02 sq mi (0.05 km2) 0.31% |

| Elevation | 2,139 ft (652 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 2,577 |

| • Density | 432.31/sq mi (166.90/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-8 (Pacific (PST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-7 (PDT) |

| ZIP code | 95310 |

| Area code | 209 |

| FIPS code | 06-14904 |

| GNIS feature IDs | 277490, 2407648 |

| Reference no. | 123[3] |

Columbia is a census-designated place (CDP) located in the Sierra Nevada foothills in Tuolumne County, California, United States. It was founded as a boomtown in 1850 when gold was found during the California Gold Rush, and was known as the "Gem of the Southern Mines."

The town's historic central district is within the Columbia State Historic Park, which preserves the 19th century mining town legacy. The U.S. historic district is a National Historic Landmark District and is on the National Register of Historic Places.

Geography

[edit]Columbia is located along State Route 49 just north of Sonora, at an altitude of 2,139 feet (652 m).

According to the United States Census Bureau, the CDP has a total area of 6.0 square miles (16 km2). Only 0.31% of the total area is covered by water.

Climate

[edit]This region experiences hot and dry summers, with no average monthly temperatures above 90.1 °F (32.3 °C). According to the Köppen Climate Classification system, Columbia has a warm-summer Mediterranean climate, abbreviated "Csb" on climate maps.[4]

History

[edit]

The original indigenous people in the Columbia region were the Miwok.

Rev. John Steele wrote about his time in the gold rush era and about the "Mi-wuk" of Columbia in his memoirs In Camp and Cabin.

Within weeks of finding gold in the vicinity of Columbia, thousands of people arrived and the population climbed to 5,000. By 1852, there were 8 hotels, 4 banks, 17 general stores, 2 bookstores, 1 newspaper, 3 churches, and over 40 drinking/gambling establishments. Between 1850 and the early 1900s, $87 million (~$2.47 billion in 2023) in gold was removed from the surrounding hills.

In 1851, the local community brass band, a popular institution, greeted the arrival of the first "white woman" in town.[5] Columbia had five cemeteries, including a Boot Hill, where burials were made without markers.[6]

In 1854, Columbia's first major fire destroyed a majority of the city. The wealthier merchants began rebuilding their business using brick with iron construction materials, the remainder of town was rebuilt of wood and canvas. In 1857, another fire burned down nearly everything else, except three brick buildings. The Columbia one-room school house was built in 1860, renovated in 1872, and finally closed in 1937. It was purchased by the state of California for $1 in 1947, and incorporated into the historic district park.

According to the 1954 episode "11,000 Miners Can't Be Wrong" of the western anthology series Death Valley Days, Columbia lost out in an 1854 bid to become the permanent California state capitol: When Jim Hardwicke, a respected settler, informs the sheriff that he had killed a man in self-defense, Hardwicke is forced to stand trial. Because of jury tampering by a corrupt district attorney, Hardwicke was found guilty. His lawyer, Ed Barrett and his fiancée develop a bizarre scheme to free his client from the hangman's noose; Barrett steals from a safe in the local bank a petition with 11,000 signatures of persons who at the instigation of the same district attorney want Columbia to be the capital, rewrites the first page to call for a pardon for Hardwicke and appeals to the governor, who is impressed that so many signed. The governor orders Hardwicke's release, but Sacramento became the capital.[7] However, the series' episodes tended to be "based on fact" rather than historically accurate.

By 1860, the gold mined in Columbia was diminishing rapidly. The only land left to mine was in the city itself. Miners dug under buildings and tore down houses to get at the gold beneath the city. Copper deposits were found in the area, with the nearby town of Copperopolis experiencing a boom. The bricks from the destroyed buildings in Columbia were sold for new construction in Copperopolis.

In 1862, just days after the Battle of Puebla in Mexico, Columbia was the site of the first official Cinco de Mayo celebrations. According to a paper published by the UCLA Center for the Study of Latino Health and Culture about the origin of the observance of Cinco de Mayo in the United States, the modern American focus on that day first started in Columbia in response to the resistance to French rule in Mexico.[8] "Far up in the gold country town of Columbia, California, Mexican miners were so overjoyed at the news that they spontaneously fired off rifle shots and fireworks, sang patriotic songs and made impromptu speeches."[9]

Columbia, in its heyday, was California's fifth-largest city, boasting a population of about 25,000 people[citation needed] although only about 2,000 people now live in this region. Unlike many gold rush boomtowns, Columbia never became a ghost town. In 1934 under a state sponsored New Deal program of archaeological research, the SERA (State Emergency Relief Administration) hired 65 research workers at U.C. Berkeley's Bancroft Library and 56 additional workers in the field to gather the necessary information to provide for the restoration of the old town.[10] In 1945, California created Columbia State Historic Park from the remains of the historical buildings of the city.

Visitor attractions

[edit]

Columbia's main street in the historic district, part of the Columbia State Historic Park, is closed to automobile traffic, but horses, carriages, bicycles and pedestrians are welcomed. Known for the huge rock gardens left over from the hydro mining efforts in the 1800s, the area is very popular with families for picnicking and leisurely walks. The antique buildings are leased to era-themed businesses such as gold-panning, candle-dipping, iron-mongering, and crafts. There are several eating establishments. A chicken coop with beautiful Dominique hens lends a sweet background sound to Main Street. A horse-drawn stagecoach ride for a fee is the main attraction. There are numerous events throughout the year; some of the notable occasions are the Fourth of July parade and Columbia Diggins 1852. Occasionally local crafters set up booths along Main Street. Costumed State Park employees and shopkeepers lend to the era-theme of the park. Picnic tables are situated throughout the downtown. There is a short hiking trail from the School House, which is located a couple of blocks from the town. The school is open with static exhibits. Two campgrounds nearby accommodate tenting and motorhomes, as well as a small general store for supplies.

Other points of interest in the area include Columbia Community College, a two-year, community college; and the Columbia Airport (FAA designator: O22), which has one 4,670-foot (1,420 m) runway and is busy with firefighting aircraft during summer.

The annual Columbia Fire Muster here is often the earliest of California's summer musters.

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 2,405 | — | |

| 2010 | 2,297 | −4.5% | |

| 2020 | 2,577 | 12.2% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[11] 1850–1870[12][13] 1880-1890[14] 1900[15] 1910[16] 1920[17] 1930[18] 1940[19] 1950[20] 1960[21] 1970[22] 1980[23] 1990[24] 2000[25] 2010[26] | |||

2010

[edit]The 2010 United States Census[27] reported that Columbia had a population of 2,297. The population density was 384.1 inhabitants per square mile (148.3/km2). The racial makeup of Columbia was 2,064 (89.9%) White, 27 (1.2%) African American, 26 (1.1%) Native American, 29 (1.3%) Asian, 1 (0.0%) Pacific Islander, 27 (1.2%) from other races, and 123 (5.4%) from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 171 persons (7.4%).

The Census reported that 2,226 people (96.9% of the population) lived in households, 71 (3.1%) lived in non-institutionalized group quarters, and 0 (0%) were institutionalized.

There were 1,002 households, out of which 243 (24.3%) had children under the age of 18 living in them, 432 (43.1%) were opposite-sex married couples living together, 125 (12.5%) had a female householder with no husband present, 51 (5.1%) had a male householder with no wife present. There were 53 (5.3%) unmarried opposite-sex partnerships, and 4 (0.4%) same-sex married couples or partnerships. 330 households (32.9%) were made up of individuals, and 142 (14.2%) had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.22. There were 608 families (60.7% of all households); the average family size was 2.80.

The population was spread out, with 470 people (20.5%) under the age of 18, 201 people (8.8%) aged 18 to 24, 406 people (17.7%) aged 25 to 44, 735 people (32.0%) aged 45 to 64, and 485 people (21.1%) who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 47.8 years. For every 100 females, there were 97.3 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 92.9 males.

There were 1,117 housing units at an average density of 186.8 per square mile (72.1/km2), of which 661 (66.0%) were owner-occupied, and 341 (34.0%) were occupied by renters. The homeowner vacancy rate was 2.1%; the rental vacancy rate was 8.1%. 1,389 people (60.5% of the population) lived in owner-occupied housing units and 837 people (36.4%) lived in rental housing units.

2000

[edit]As of the census[28] of 2000, there were 2,405 people, 1,063 households, and 659 families residing in the CDP. The population density was 389.7 inhabitants per square mile (150.5/km2). There were 1,162 housing units at an average density of 188.3 per square mile (72.7/km2). The racial makeup of the CDP was 90.10% White, 0.87% African American, 1.41% Native American, 1.29% Asian, 0.12% Pacific Islander, 1.29% from other races, and 4.91% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 6.90% of the population.

There were 1,063 households, out of which 22.6% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 44.3% were married couples living together, 13.0% had a female householder with no husband present, and 38.0% were non-families. 29.7% of all households were made up of individuals, and 14.3% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.18 and the average family size was 2.65.

In the CDP, the population was spread out, with 20.2% under the age of 18, 10.0% from 18 to 24, 18.8% from 25 to 44, 28.1% from 45 to 64, and 22.9% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 46 years. For every 100 females, there were 89.1 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 88.4 males.

The median income for a household in the CDP was $29,173, and the median income for a family was $35,000. Males had a median income of $40,729 versus $23,750 for females. The per capita income for the CDP was $18,731. About 20.2% of families and 19.0% of the population were below the poverty line, including 37.7% of those under age 18 and 1.4% of those age 65 or over.

Notable people

[edit]- Delmer Berg, veteran of both the Spanish Civil War and World War II, lived in Columbia.[29]

- Jon Robert Cavaiani, Medal of Honor recipient who lived in Columbia.[30]

- Drew Gagnon, Major League and KBO pitcher, was born in Columbia.[31]

- Red Kress, Major League Baseball player and coach, was born in Columbia.[32]

- Peter Muldoon, Roman Catholic Bishop of the Diocese of Rockford, was born in Columbia.[33]

- Slim Pickens, actor, lived in Columbia in the last decades of his life and was a member of the Church of the 49er.[34]

- Keith Matthew Emerald, hunter, Columbia resident who started the illegal campfire in 2013 that caused the ‘Rim Fire’ wildfire, the 5th largest wildfire in CA history, which destroyed parts of Yosemite National Park, and which burned for a year.[35]

As a filming location

[edit]A few of the more than 100 movies and TV series filmed in Columbia include:

- Sierra Spirits, 2007

- Behind the Mask of Zorro, 2005

- Radio Flyer, 1992

- Blood Red, 1989

- Pale Rider, 1985

- The Shadow Riders, 1982

- Joe Dancer: The Big Trade, 1981

- The Last Ride of the Dalton Gang, 1979

- Law of the Land, 1976

- Little House on the Prairie, 1974

- Something for a Lonely Man, 1968

- Bullwhip, 1958

- Rage at Dawn, 1955

- Texas Lady, 1955

- The Cimarron Kid, 1952

- Death Valley Days, 1952

- High Noon, 1952

- The Lone Ranger, 1949

- The Red House, 1947

- Rustlers' Valley, 1937

- Wells Fargo, 1937

- The Best Bad Man, 1925

- Timber Stampede, 1939

Government

[edit]In the California State Legislature, Columbia is in the 8th Senate District, represented by Democrat Angelique Ashby, and in the 5th Assembly District, represented by Republican Joe Patterson.[36]

In the United States House of Representatives, Columbia is in California's 4th congressional district, represented by Democrat Mike Thompson.[37]

Airport

[edit]The Columbia Airport, a general aviation airfield located approximately one mile from the city, is home to an aerial firefighting air attack base operated by the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (Cal Fire) which bases fixed-wing turboprop aircraft as well as a helicopter there.

Notes

[edit]- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 30, 2021.

- ^ "Columbia". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved November 4, 2014.

- ^ "Columbia". Office of Historic Preservation, California State Parks. Retrieved October 18, 2012.

- ^ Climate Summary for Columbia, California

- ^ Abel, pg. 133

- ^ Hoover, pg. 223

- ^ "11,000 Miners Can't Be Wrong on Death Valley Days". Internet Movie Data Base. September 25, 1954. Retrieved August 20, 2018.

- ^ Southern California Quarterly "Cinco de Mayo's First Seventy-Five Years in Alta California: From Spontaneous Behavior to Sedimented Memory, 1862 to 1937" Spring 2007 (see American observation of Cinco de Mayo started in California) Retrieved October 30, 2007.

- ^ Hayes-Bautista, David E. (April 2009). "Cinco de Mayo: The Real Story". EGP News. Eastern Group Publications. Archived from the original on June 12, 2016. Retrieved June 2, 2016.

Far up in the gold country town of Columbia (now Columbia State Park) Mexican miners were so overjoyed at the news that they spontaneously fired off rifles shots and fireworks, sang patriotic songs and made impromptu speeches.

- ^ Mariposa Gazette December 9, 1934

- ^ "Decennial Census by Decade". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "1870 Census of Population - Population of Civil Divisions less than Counties - California - Almeda County to Sutter County" (PDF). United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "1870 Census of Population - Population of Civil Divisions less than Counties - California - Tehama County to Yuba County" (PDF). United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "1890 Census of Population - Population of California by Minor Civil Divisions" (PDF). United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "1900 Census of Population - Population of California by Counties and Minor Civil Divisions" (PDF). United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "1910 Census of Population - Supplement for California" (PDF). United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "1920 Census of Population - Number of Inhabitants - California" (PDF). United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "1930 Census of Population - Number and Distribution of Inhabitants - California" (PDF). United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "1940 Census of Population - Number of Inhabitants - California" (PDF). United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "1950 Census of Population - Number of Inhabitants - California" (PDF). United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "1960 Census of Population - General population Characteristics - California" (PDF). United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "1970 Census of Population - Number of Inhabitants - California" (PDF). United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "1980 Census of Population - Number of Inhabitants - California" (PDF). United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "1990 Census of Population - Population and Housing Unit Counts - California" (PDF). United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "2000 Census of Population - Population and Housing Unit Counts - California" (PDF). United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "2010 Census of Population - Population and Housing Unit Counts - California" (PDF). United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "2010 Census Interactive Population Search: CA - Columbia CDP". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 15, 2014. Retrieved July 12, 2014.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ^ California Vets: Del Berg and Jim Benét July 2, 2012, retrieved 2019-02-27

- ^ Jon Cavaiani, Medal of Honor Recipient in 1974, Dies at 70

- ^ "Drew Gagnon". Baseball Reference.com. Retrieved February 23, 2021.

- ^ Baseball Reference.com.-Red Kress

- ^ Peter James Muldoon

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "How a rodeo and needing to lie to his father, gave SLIM PICKENS his Hollywood name!". YouTube.

- ^ "Feds dismiss Rim Fire indictment against Keith Emerald". ABC 30. May 2, 2015. Retrieved February 23, 2021.

- ^ "Statewide Database". UC Regents. Archived from the original on February 1, 2015. Retrieved November 23, 2014.

- ^ "California's 4th Congressional District - Representatives & District Map". Civic Impulse, LLC. Retrieved September 28, 2014.

References

[edit]- Abel, E. Lawrence (2000). Singing the New Nation: How Music Shaped the Confederacy, 1861-1865. Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole Books. ISBN 0-8117-0228-6.

- Hoover, Mildred B.; Douglas E. Kyle (2002). Historic Spots in California. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-4482-9.

External links

[edit]- Columbia Chamber of Commerce

- Columbia State Historic Park

- Columbia mining history and historic photos from Western Mining History

- Photographic Tour of the Bell Marble Quarry, Columbia, CA, on Stone Quarries and Beyond.

- Photographic Tour of One of the Historic Columbia Marble Quarries, Columbia, CA, on Stone Quarries and Beyond.

- myMotherLode.com Community Guide